A time and a place

A time and a place

Satire is usually deeply rooted in current affairs. Satirical artists use their trade to comment upon well-known events. They play on popular opinions and fears to thrill, amuse and entertain their audiences, and ultimately to sell their work.

Scientific breakthroughs, philosophical leaps, political wrangling and pandemics are just some of the subjects found in our satirical print collection. These images require us to understand the contexts in which they were produced before we can decipher what the artists wanted to convey. In some cases, the full context is not known and the messages remain a mystery.

Today, satirical images from the past can show us the human responses to a wide range of past events, both significant and mundane, and can help us to understand common assumptions and experiences of the time.

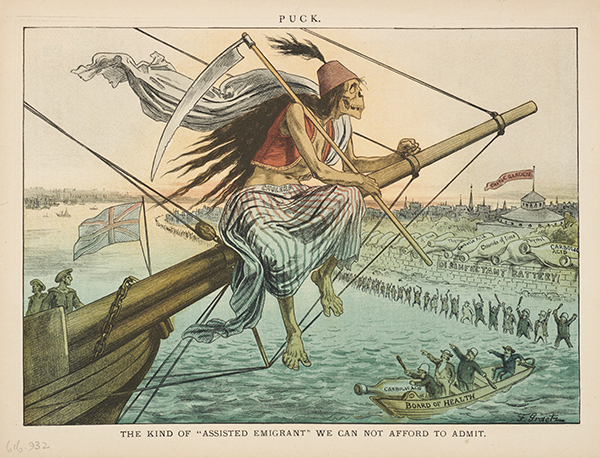

The kind of ‘assisted emigrant’ we can not afford to admit

The kind of ‘assisted emigrant’ we can not afford to admit

Coloured engraving after Friedrich Graetz, published in Puck, New York City, 18 July 1883

PR15066

High on the bow of an English ship, a skeletal immigrant holding a scythe gazes towards Manhattan Island. The skeleton is Death, and he is bringing the foreign disease of cholera to the US.

In the background, bottle-shaped canons fire disinfectant towards the ship, and the Board of Health tries to prevent it from entering. In the distance is Castle Garden – now Castle Clinton – the US’s immigrant processing centre between 1855 and 1890.

In this political print, the Austrian cartoonist Friedrich Graetz captures the public’s fear of disease, death and immigration. Cholera was an acute, often fatal illness caused by infection of the intestine from drinking contaminated water, which spread swiftly across Asia and Europe in the 19th century. It is believed that English immigrants brought the disease to the US in 1832. Over the next 30 years the US had three serious waves of the disease, and New York was the first city to feel the impact.

Immigration to the US increased rapidly in the 19th century, and emigrants were often ‘assisted’ to leave by the government of their home country. Published in 1883, this image plays on general xenophobic ideas surrounding immigration. The figure of Cholera wears Turkish clothing, perhaps showing fear of the Turkish-Cypriot immigrants who came to the US following the 1878 Ottoman handover of Cyprus to Britain. This sentiment is familiar today in the enduring anti-immigrant rhetoric in modern politics.

View catalogue entry for The Kind of "Assisted emigrant" we can not afford to admit

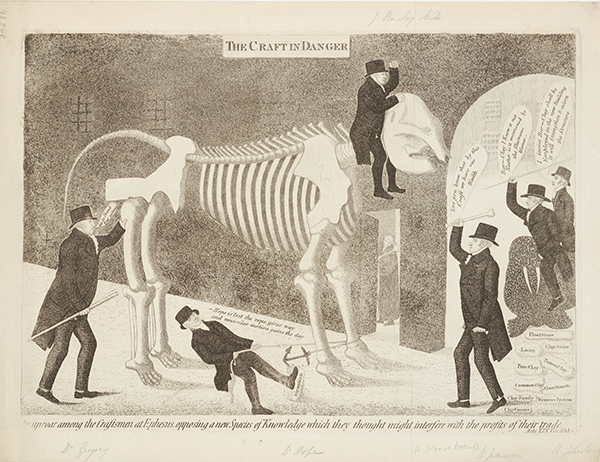

The craft in danger

The craft in danger

Engraving by J Kay, 1817

PR164a

Dr John Barclay (1758–1826), anatomy teacher at the University of Edinburgh, rides an elephant skeleton into the university’s gates. In 1817 Barclay was put forward by the university as the new chair (professor) of comparative anatomy – a proposal that was not universally accepted by Barclay’s colleagues.

Barclay’s elephant is a reference to his use of skeletons from his own collections – in particular his Asian elephant – to illustrate his lectures. The elephant is being pushed forward by Barclay’s only supporter, Dr James Gregory (1753–1821), who was professor of medicine at the University of Edinburgh.

The other figures in the scene are colleagues who opposed and eventually defeated the proposal to make Barclay chair of comparative anatomy. Beneath the elephant the English doctor Thomas Charles Hope (1766–1844) falls while attempting to break the animal’s stride. Blocking the entrance to the university are the professor of medicine and botany John Hope (1725–1786), the professor of natural history Robert Jameson (1774–1854), and the chair of anatomy at the medical school, Alexander Monro the Third (1773–1859).

These professors feared that the proposed chair would threaten their position within the university and put their ‘craft’ in danger. In 1798 Monro’s father had donated his anatomical collection to the anatomy department; perhaps Monro felt that Barclay’s promotion would diminish his family’s prominence within the faculty.

We do not know how widely understood this image would have been at the time by viewers outside of the university, and today we can only understand it with specific knowledge of the feud it depicts.

Part of the exhibition A taste of one's own medicine. Explore further: