Spitting image

Spitting image

Medical professionals were frequently targeted by satirists and caricaturists. Like other civic figures such as priests, lawyers and politicians, individual doctors and surgeons gained public reputations that were critiqued and perpetuated in satirical images.

Medical specialisms, preferred treatments, personality traits and social backgrounds were all the subject of satire. Caricatures about specific individuals were made identifiable through exaggerated facial features, verbal puns, text and labels. In some cases, caricatures were closely related to existing portraits, relying on the viewer’s knowledge of works of art for recognition.

The production of satirical prints hugely increased during the 18th and 19th centuries, following a drop in the cost of printmaking. Images that were previously consumed by the wealthy were reproduced in the hundreds and thousands and could be viewed in broadsheet newspapers and everyday places such as taverns, barber shops, smoking rooms and brothels. Images of medical professionals were seen across all levels of society, and caricatures of doctors in particular would have been easily recognised, with their stereotypical wig, cane, and pompous expression.

Today, surviving satirical prints help us understand how medical professionals were perceived and judged. This shifted considerably during the 18th and 19th centuries, away from focusing on distrust of the medical professions and the inherent violence of medical intervention, towards the mocking of perceived pretensions.

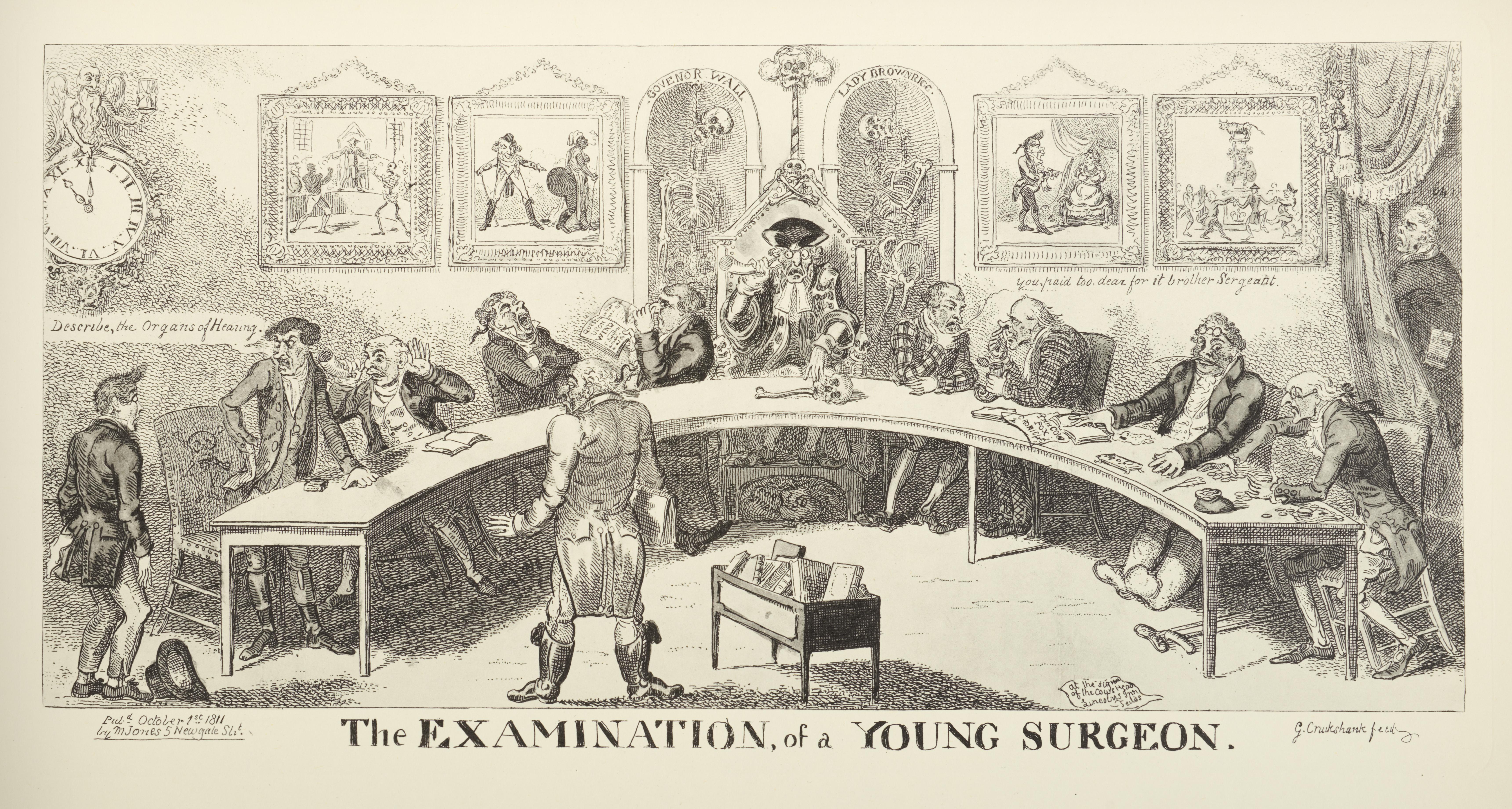

The examination of a young surgeon

The examination of a young surgeon

Coloured etching by George Cruikshank, published in ‘The scourge; or, monthly expositor, of imposture and folly’, vol 2, by M Jones, London, 1811 (possibly a later copy)

2008.1/3

Founded in 1800, the College of Surgeons controlled surgical practice in and around London. The College’s standards were criticised by prominent satirists including George Cruikshank (1792–1878), who regularly drew caricatures for the English periodical ‘The scourge’.

This print accompanied the article ‘Medical science exemplified’, which mocks the College’s education and examination of surgeons. It describes the board of ten examiners, represented in the caricature, including ‘one gentleman [who] was so old and sleepy that he asked you a question, “describe the organs of hearing, Sir,” and fell a snoring before you could reach the tympanum [eardrum]’.

The young surgeon to the left of the scene is unidentified, but the examiners behind the table are those mentioned in the article. The Master examiner in the central high chair is Sir Charles Blicke (1745–1815), who was deaf and known to hoard money – he is depicted with an ear trumpet and bags of cash below his chair. To his left, the figures in tartan are the Scottish Serjeant-surgeons Sir David Dundas (1749–1826) and Sir Everard Home (1756–1832). Dundas is supposed to have gained his position through royal connections, and Home allegedly destroyed manuscripts belonging to the surgeon John Hunter (1728–1793).

To Home’s left is the Scottish physician Edward Jenner (1749–1823), who created the smallpox vaccine from samples of cowpox – he is identified by the paper in front of him which reads 'THH [sic] COW POX CRONICLE'.

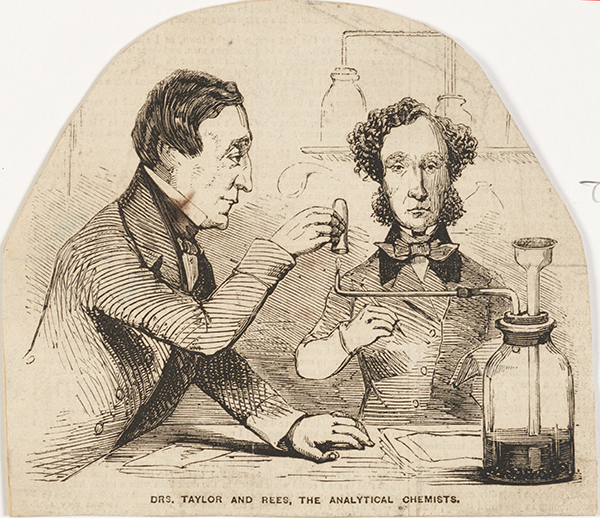

Drs Taylor and Rees, the analytical chemists

Drs Taylor and Rees, the analytical chemists

Newspaper engraving from The illustrated times, London, 2 February 1856

PR15076

The ‘analytical chemists’ are Drs Alfred Swaine Taylor (1806–1880), a pioneer in British forensic medicine, and George Owen Rees (1813–1889), a physician at Pentonville Prison and Guy’s Hospital, London. In 1856 Taylor and Rees both gave damning testimonies in the famous trial of William Palmer, the so-called ‘Rugeley poisoner’.

Taylor and Rees are carrying out chemical experiments, perhaps a reference to their testimonies as expert witnesses in the trial. Their heads are enlarged and their facial features and hairstyles are exaggerated – a common stylistic trait used by caricaturists to create unflattering images and to draw attention to distinguishing features.

This image appeared in the Illustrated times weekly newspaper, a cheaper, popular paper first published in 1855 by Fleet Street bookseller David Bogue as a rival to the dominant Illustrated London news. During the 19th century illustrated newspapers became increasingly successful, allowing greater public exposure to visual satire. Surviving caricatures from before this period were more exclusive to the wealthy who bought them as ephemera, although cheaply produced copies would have been visible to all in print shop windows and public houses.

View the catalogue entry for Drs Taylor and Rees, the analytical chemists

‘Lord Beaconsfield’s Physician’ Richard Quain (1816–1898)

‘Lord Beaconsfield’s Physician’ Richard Quain (1816–1898)

Chromolithograph by Vincent Brooks Day and Son Ltd after Leslie Ward ‘Spy’, in Vanity Fair, 15 December 1883

PR10401

Standing full length with his right hand tucked into his coat, an enlarged head and baggy clothing, Irish physician Sir Richard Quain is gently satirised in this image by the Vanity Fair illustrator Leslie Ward, also known as ‘Spy’.

Between 1860 and 1914, 53 well-known doctors were depicted in Vanity Fair, which described itself as ‘A weekly show of political, social and literary wares’. The magazine aimed to truthfully expose the contemporary vanities of Victorian society, without singing praises or diminishing merit. Inclusion was considered an accolade, and the portraits were humorous and friendly rather than mocking or malicious. Quain’s accompanying biography describes him as ‘an amiable and agreeable man, full of good stories’.

For Vanity Fair’s satirical portraits to work, their subjects needed to be recognisable. Quain was well known in London society. He worked at the Brompton Hospital for Diseases of the Chest and held senior positions at the RCP and other medical organisations. In 1881 Queen Victoria asked him to care for prime minister Benjamin Disraeli during his final days, and he later became the queen’s doctor, which kept him in the public eye.

In the second half of the 19th century, doctors were no longer depicted inflicting violent treatments (such as bloodletting) upon patients. This shift may reflect a greater level of esteem held by the public towards the medical professions. The practice of medicine was advancing technically with the widespread use of anaesthesia, anti-sepsis and X-rays, making diagnosis and treatment more comfortable and reliable. The emergence of medical specialties with highly skilled individuals, and the standardisation of competence set out by the 1858 Medical Act, helped to increase public confidence in doctors and their abilities.

View catalogue entry for 'Lord Beaconsfield's Physician' Richard Quain

Part of the exhibition A taste of one's own medicine. Explore further: