Related pages

Goodbye John Dee!

Over the past 6 months, we had become accustomed to the presence of a new friend who had taken up temporary residence on our first floor gallery.

Code making and code breaking: John Dee and the art of cryptography

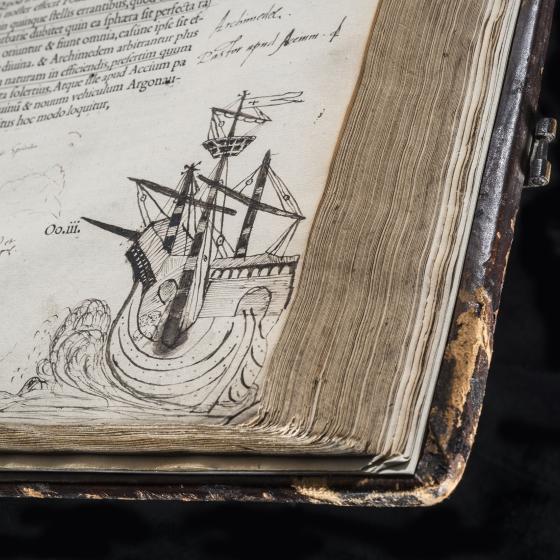

Renaissance polymath John Dee had many interests including cryptography, the art and science of making and breaking codes. Among the books once owned by Dee now in the RCP library is a copy of a cryptographic treatise by Johann Trithemius.

‘Rapt in secret studies’: was Shakespeare’s Prospero inspired by John Dee?

In Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, the character Prospero uses magical powers to intimidate his enemies and to manipulate the natural world. The character may have been inspired by the Elizabethan mathematician, astrologer and book collector John Dee.

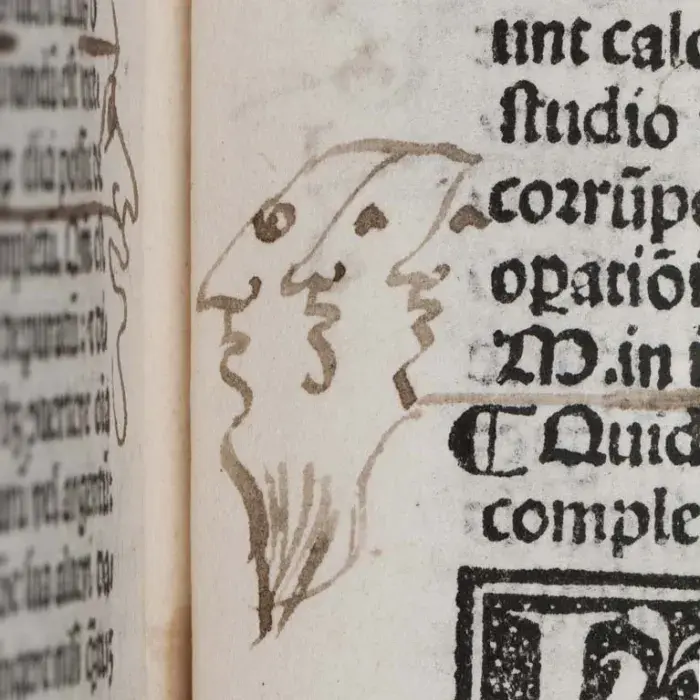

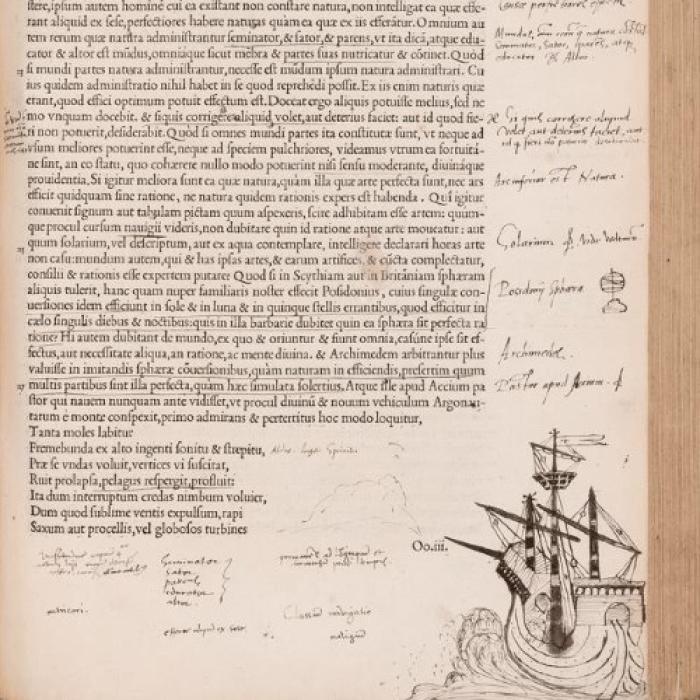

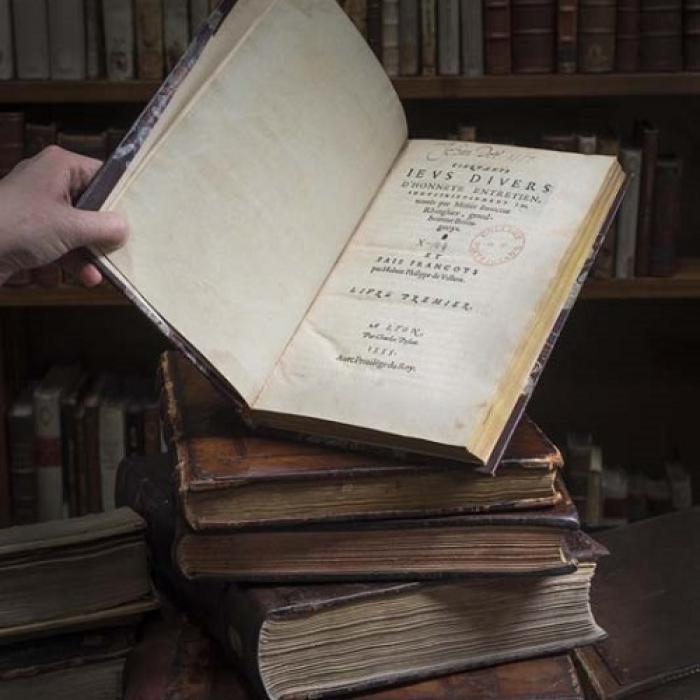

This book belongs to… : John Dee’s library at the RCP

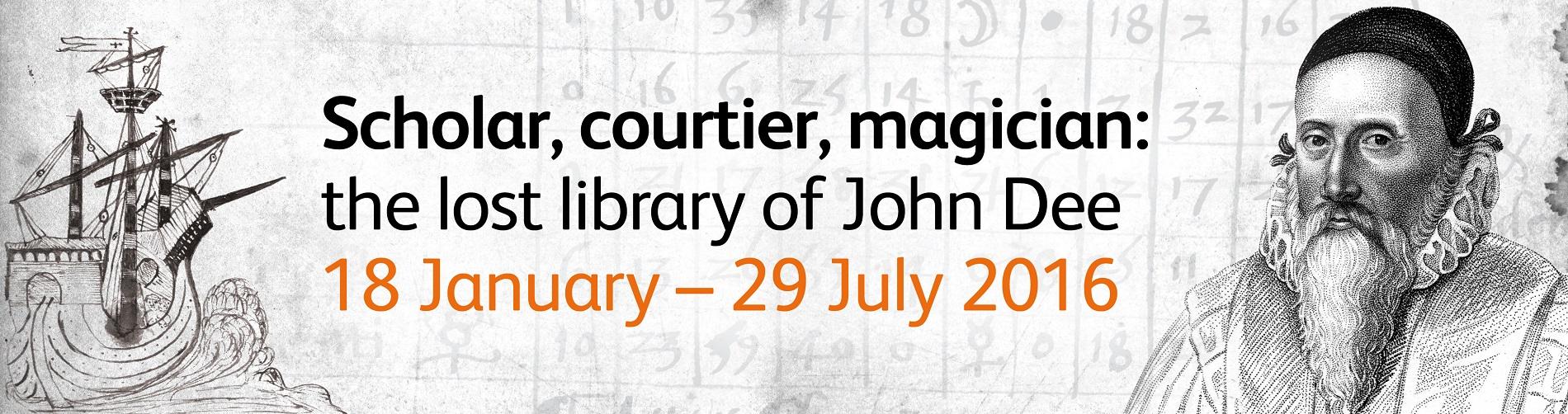

The RCP library contains the largest known collection of books from the library of the Elizabethan polymath John Dee (1527–1609). These are being displayed for the first time in the current RCP exhibition, ‘Scholar, courtier, magician: the lost library of John Dee’.

Exhibiting the lost library of John Dee

We’re currently putting the finishing touches onto our new exhibition, ‘Scholar, courtier, magician: the lost library of John Dee’, which will open to the public on Monday 18 January 2016.