RCP unseen teaching doctors

RCP Unseen: teaching doctors

Teaching medicine and training doctors have always been core functions of the RCP. How doctors have experienced this has changed dramatically over the centuries.

Some items, on display here for the first time, reveal another rarely heard voice in the collections: that of the medical student.

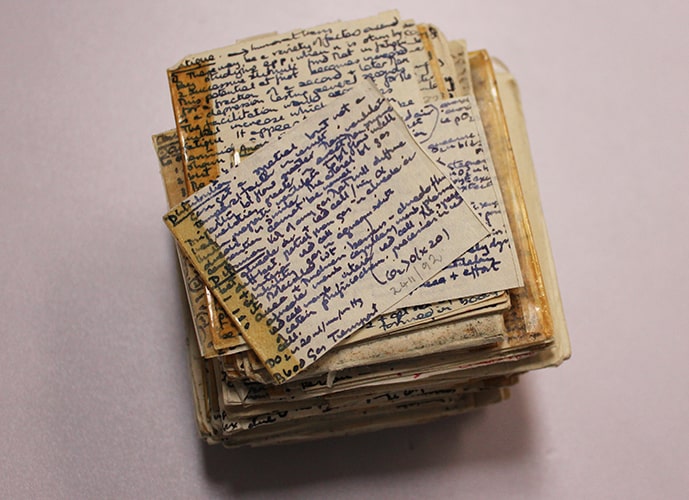

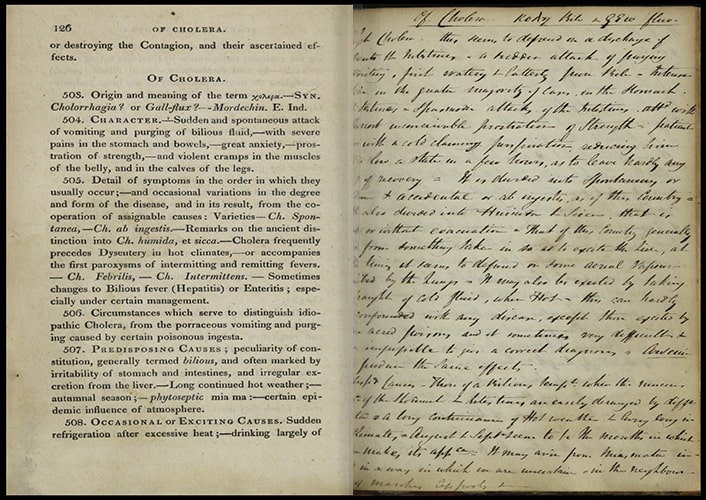

Copy of a physiology textbook, used as a crib sheet in an examination

Copy of a physiology textbook, used as a crib sheet in an examination, England, c.1970s (MS2411/92)

This tiny set of notes, written in extremely neat handwriting, was smuggled into an RCP examination. Unfortunately for the candidate they were caught, and this miniature textbook ended up in the RCP’s misconduct files.

Physicians in the UK go through a rigorous series of theory and practical examinations. Even a cheat sheet as well-organised as this one would not help a doctor to pass if they did not know their subject.

View catalogue entry for Copy of physiology textbook, used as a crib sheet in an examination

Oral history transcript: Linda Luxon clinical finals

Biography:

Professor Linda Luxon studied medicine at St Thomas’ Hospital, London. She specialised in neuro-otology and was the first female consultant physician at the National Hospital, Queen Square as well as the first female treasurer of the RCP. Professor Luxon also held the chair in Audiological Medicine at University College London. Interviewer: Lynda Finn.

Transcript:

Linda Luxon recalls a kind patient and examiner who helped to settle her nerves in clinical finals:

I have to admit, it’s almost cheating so I don’t like to admit it, one of the long cases which was a woman that had an abdominal complaint, I think I was the only woman that had come through that day, she obviously decided she wanted to help me so she was very forthcoming in exactly what was wrong with her, exactly what the signs were. Fortunately I think I did pick them up [laughs] but she was very nice and so, it was fine. But I hated doing exams, I was never a confident person in exams. And one of the other things that happened was one of the short cases was somebody with thyrotoxicosis, that had a big goitre and was shaking and poppy eyes. And I really wasn’t in any doubt what this woman had and how we should treat it, that was all fine, but in the horror of exams I said completely the opposite. I said, “This woman’s got myxoedema,” I mean, it was only because I was absolutely panic-stricken. And the examiner looked at me and said, “Are you sure that’s what this lady’s got?” And fortunately again, I suddenly realised what I’d done, I said, “No, no, no, I don’t mean that at all, she’s got thyrotoxicosis,” and then said all the correct things. And he was very nice, he smiled and said, “I thought that’s what you meant.”

Oral history transcript: John Bennett on MRCP exams

Biography:

Biography:

Dr John Bennett was born in Merseyside and studied medicine at Liverpool University. Following junior posts in Liverpool, Birmingham and London he was appointed as consultant physician in general medicine and gastroenterology at Hull Royal Infirmary. Here he shares his memories of taking the MRCP pathology viva.

Interviewer: Eric Beck.

Transcript:

John Bennett remembers how the extreme stress that he felt taking the MRCP exams re-surfaced unexpectedly years after he had passed:

I thought it was a beastly exam. These, you know, these rather superior London physicians used to regard it as their little patch. It was long before the reformation. I think the reformation was in line, but it was a very old-fashioned exam. I mean these papers and these clinicals and if you got through the clinicals you had this path viva. When I’d been a consultant a few years, on election day I went to our local church hall to vote and as I went in, for reasons quite unclear to me, I was seized by icy dread round my heart. And it took me a long time to understand this. And then I realised it was the path viva again. I had a piece of paper in my hand and I was walking towards a trestle table with two people behind it looking at me expectantly and it really had sunk deeply into my subconscious.

Oral history transcript: David London and MRCP

Biography:

Biography:

Professor David London studied medicine at Oxford University and St Thomas’ Hospital before becoming a consultant physician in endocrinology at Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham. He was the Registrar of the Royal College of Physicians from 1992 – 1998.

Transcript:

In this clip David recalls the dreaded pathology viva of the old style MRCP exam:

I took the exam twice as I think I mentioned to you. On the first occasion, I quite clearly failed the path viva because I was given a pot that I could not identify and I was always bad at identifying pathology specimens, we called them pots. And I can remember what it was, it was a cut out myocardial infarct that was very old and when I moved the pot it was just like one of these snowstorm little ornaments, everything floated up and floated – and I couldn’t identify it. If I’d identified it, it would have been easy because I could have spoken about the subject, but I spent most of the viva not identifying it. On the second time I took the membership, again I couldn’t identify the pot. I said it was something – what did I say it was? I said it was Hodgkin’s of the liver, but actually it was sarcoid of the spleen. And the examiner said, “Oh, it doesn’t matter,” he said, “it’s actually sarcoid, tell me about sarcoid,” so I told him about sarcoid. He then gave me another pot which actually not only could I identify, but it was my specialist subject, it was endocrinology.

Reproduced courtesy of the Wiley Digital Archives © John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Outlines of a course of lectures on the practice of medicine delivered in the medical school of Guy's Hospital

Henry James Cholmeley, Outlines of a course of lectures on the practice of medicine delivered in the medical school of Guy's Hospital, London, 1820 (CN54923)

These lecture notes have been bound with sheets of blank paper between the printed pages, leaving lots of space for a student to take their own notes about what they've read, heard and seen.

We don't know the identity of the student who wrote these comments on the infectious disease cholera. They noted that disease can reduce a patient to ‘so low a state in few hours, as to leave hardly any hope of recovery’.

The lecturer Henry James Cholmeley was a fellow of the RCP and physician to Guy's Hospital from 1811 until his death in 1837.

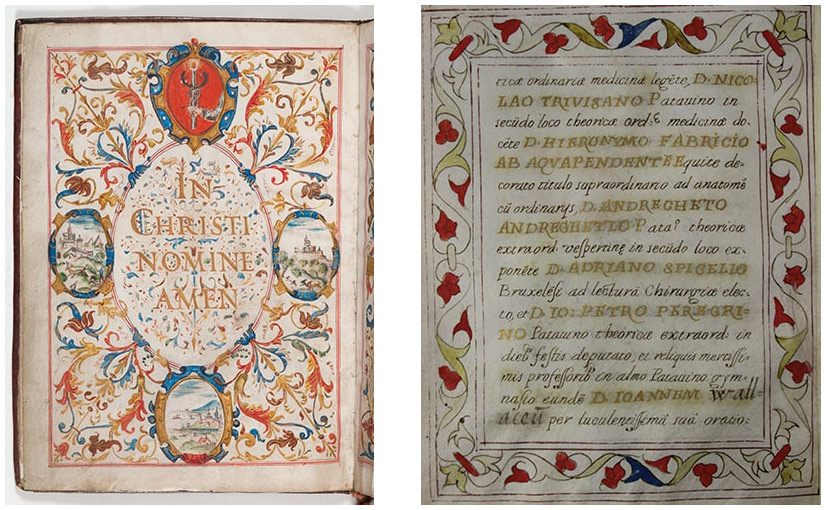

Left: Diploma of Medicine granted to William Harvey.

Right: Forged medical diploma from the University of Padua. Reproduced courtesy of the Wiley Digital Archives © John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Diploma of Doctor of Medicine granted by the University of Padua to William Harvey

Diploma of Doctor of Medicine granted by the University of Padua to William Harvey, 25 April 1602 (MS315)

The University of Padua was one of the best places to study medicine in Europe in the early 17th century. It contained the world’s first permanent anatomical theatre, opened in 1595, where students could witness dissections of human bodies. This theatre became the model for the anatomical theatres built across Europe throughout the 17th century – including the one built by the architect Robert Hooke for the College of Physician’s new Warwick Lane premises, which opened in 1679.

William Harvey (1578–1657) joined the College of Physicians in 1604 on his return from Padua. In 1616 he started a series of anatomical lectures spread over seven years which established the groundwork behind the medical discovery which made him famous – the discovery of how blood circulates around the body.

View Diploma of Doctor of Medicine granted by the University of Padua to William Harvey

Diploma of Doctor of Medicine granted by the University of Padua to unknown person

Diploma of Doctor of Medicine granted by the University of Padua to unknown person [22 January 1628] (MS702)

This diploma is a forgery. It claims to be the medical diploma of John Wallace, awarded by the University of Padua on 22 January 1628. In fact, John Wallace used a genuine medical certificate and erased the real recipient’s surname throughout, inserting his own instead.

The style in which Wallace’s surname is written does not match any of the other names in the document. It is written in black ink, rather than gold, and is not entirely in capital letters. The year has been altered from 1618 to 1628 – a mistake on Wallace’s part because the two doctors who signed the certificate, Fabrici d’Acquapendente and Adrian van de Spiegel, were dead by 1628.

We do not know if Wallace practised medicine, but he appears to have successfully misled his family and neighbours as his epitaph in St Helen’s Church, Ipswich, describes him as ‘Johannes Wallace M.D.’ Regulating physicians and the practice of medicine was a main role for the College of Physicians from its establishment in 1518. In 1858 the Medical Act transferred this role to the General Medical Council.

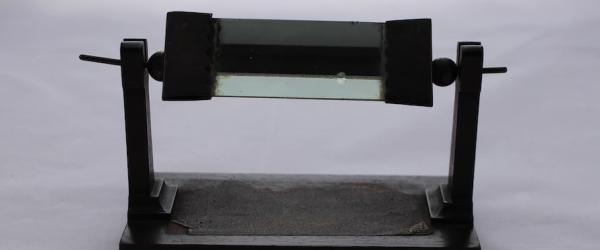

Silver mounted wood pointer

Silver mounted wood pointer c.1883 (X1052)

Doctors have had many attributes over the centuries: the white coat, stethoscope, walking cane – and the pointer, used to demonstrate and identify during teaching.

This pointer is inscribed ‘Joseph Lister, Rudolf Virchow 17/7/[18]83’ in two different hands. Rudolf Virchow (1821–1902) was a German physician and leading expert on modern pathology. Joseph Lister (1827–1912) was a surgeon famous for pioneering the use of antisepsis in surgery while working at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary – Lister introduced the use of carbolic acid to sterilise surgical instruments and to clean wounds.

We do not know why Lister and Virchow’s names are inscribed on this pointer. In 1883, Lister was created a Baronet by Queen Victoria. Both Lister and Virchow were members of the Royal Society of London at this time, and in 1901 Lister delivered a heartfelt speech in honour of Virchow’s 80th birthday, in which he described Virchow’s ‘gigantic intellectual powers’. It is possible that this pointer commemorates their professional relationship or a joint venture.

View catalogue entry for Silver mounted wood pointer

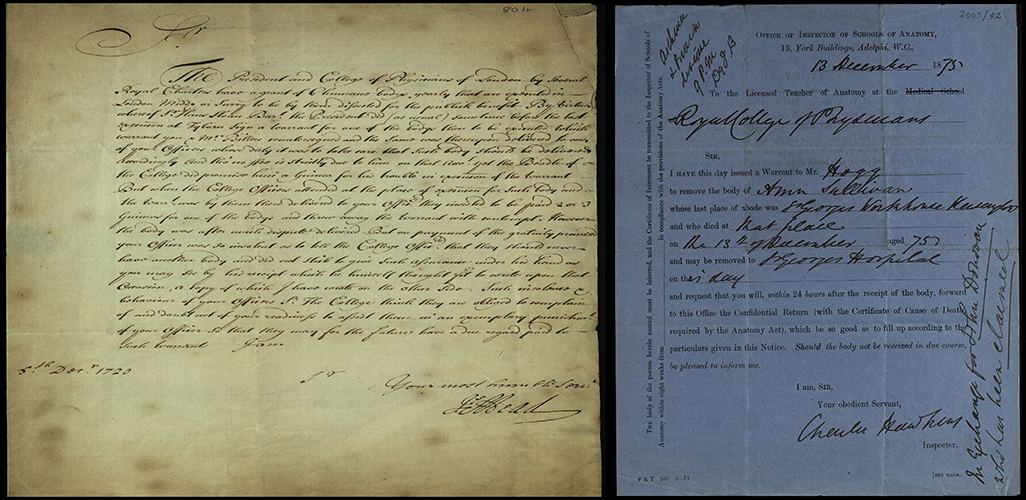

Left: Letter regarding a dispute about the supply of bodies of executed criminals.

Right: Warrant for the removal of the body of Ann Sullivan. Reproduced courtesy of the Wiley Digital Archives © John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Letter to Sir George Caswall regarding a dispute about the supply of bodies of executed criminals at Tyburn prison to the RCP for dissection

Letter to Sir George Caswall regarding a dispute about the supply of bodies of executed criminals at Tyburn prison to the Royal College of Physicians for dissection , 5 December 1720 (MS804)

The College had the right to take up to six bodies of executed criminals, fresh from the gallows at Tyburn prison every year for anatomical dissection. This right, granted by Queen Elizabeth I in 1564, was an important privilege. Reliable sources of bodies for research and teaching were very scarce.

This right led to a flourishing programme of anatomical lectures, where bodies were dissected in front of an audience of medical students and others interested in the study of anatomy. These lectures helped to establish the reputation of the young College and confirmed its status as a respected medical authority in London.

On this occasion, a body was chosen from a recent execution for the current series of lectures, as usual. However, the government officials delivering the corpse asked for extra money on top of the standard fee and caused a scene. This letter was sent to Caswall, the Sheriff of London, who oversaw the government officials. It complained about both the request for extra money and the rudeness of those officials towards the College’s representatives attending the hanging.

Warrant for the removal of the body of Ann Sullivan to St George's Hospital

Warrant for the removal of the body of Ann Sullivan to St George's Hospital, London, 13 December 1875 (MS2003/35/82)

Ann Sullivan died alone in a Kensington workhouse, and her body was immediately removed for dissection to the RCP’s anatomy lecture.

Ann washed clothes for a living, but at the age of 75 she became unable to support herself and felt her only option was to enter the workhouse. The authorities made it difficult for families to claim the bodies of loved ones from workhouses. If they could not prove they had enough money to pay for a funeral, their relative’s body could be quickly claimed by organisations such as the RCP.

Ann’s body was removed at the last minute instead of John Donovan’s, which had been claimed by family. Hopefully this means John’s family were able to give him the funeral he deserved.

View catalogue entry for Warrant for the removal of the body of Ann Sullivan to St George's Hospital

View digital copy of Warrant for the removal of the body of Ann Sullivan to St George's Hospital

Oral history transcript: Professor Nwokolo on medical research with his father

Biography:

Biography:

Professor Chuka Nwokolo studied medicine in Nigeria, qualifying in 1978 with a distinction in surgery. He is a consultant gastroenterologist at University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust, the UK’s representative on the European Board of Gastroenterology, and the current treasurer of the Royal College of Physicians.

Interviewer: Michael de Swiet

Transcript:

In this clip Professor Nwokolo remembers how, as a child, he helped his father, who was also a physician, to conduct an important piece of medical research:

I had done some research at home. My father was interested in a lung fluke. During the Nigeria/Biafra war because the local people ate raw crabs, the claws of the local crabs, and during the war they had haemoptysis and it was thought this was TB. So a lot of them were getting anti-TB treatment but were not getting better, and that is when my father thought that this might be something else and he then took sputum, looked under a microscope and found these golden yellow eggs. Well, it was paragonimiasis. He mapped out the geographical area. I used to go with him in his Volkswagen Beetle and we used to go around collecting crabs locally and crush the claws in a blender and count the eggs [interviewee correction: the parasite precursor] from the claws. So that was my first taste of research. It was fantastic, I never got paid for it but [laughs] I used to wander around with him, we’d collect all these crabs, grind them up and look at them and do what they call a cercaria count. So they had these cercaria which were obviously the precursors – basically if you ate the claw the lung fluke [precursor] would go into the gut, bore its way, pair up in the lungs [interviewee clarifies: the lung fluke precursor would go into the gut and bore its way to the lungs where they would pair up] and cause you to cough up blood and the blood would be rich in the eggs, and it goes back in the water and infects the local snail and it goes from the local snail to the local crab, and then people eat it again. So that was the lifecycle of this very interesting parasite.

Citation for Lancet paper resulting from this research:

“Outbreak of paragonimiasis in Eastern Nigeria. Nwokolo C. Lancet. 1972 Jan 1; 1(7740):32-3. doi: 10.1016 /s0140-6736/s0140-6736(72)90017-7. PMID: 4108826 No abstract available.”

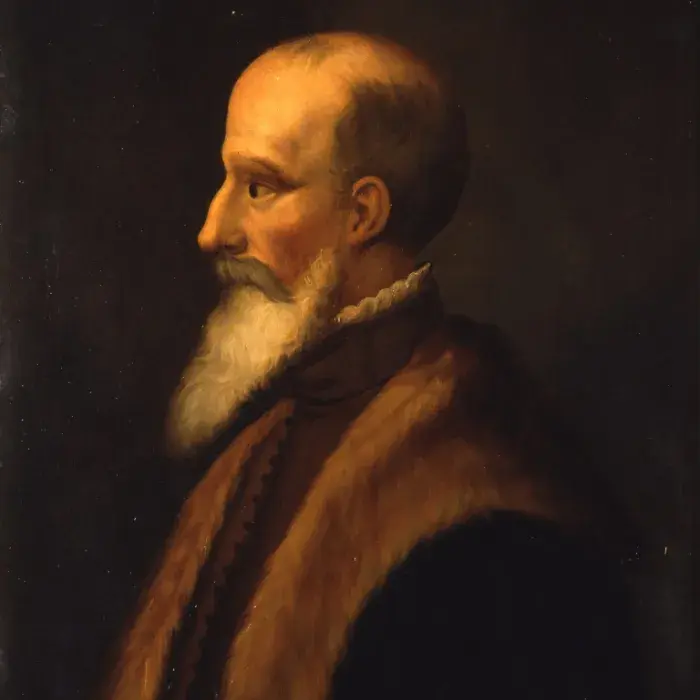

Portrait of John Caius

Portrait of John Caius, Oil on canvas by Katharine Maude Humphry, c.1880–1890 (X86)

Perhaps as significant as the eminent sitter in this portrait is the fact that it was painted by a woman artist. Of the RCP’s c.270 portraits, only 14 are known to have been painted by women. Katharine Humphry – about whom very little is known – copied the original portrait of Caius that still hangs in Caius College, Cambridge.

English physician John Caius (1510–1573) was a longstanding president of the RCP, and second founder of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. Both Caius and the college he re-established have long associations with medical teaching.

Caius was the first to introduce the study of practical anatomy – dissection – to England, and the first to teach it publicly. He was also a pioneer naturalist, travelling throughout the country to record unusual animals, in a manner similar to what would later become the science of zoology.

View catalogue entry for Portrait of John Caius

Portrait of Thomas Sydenham

Portrait of Thomas Sydenham, Oil on canvas by Mary Beale, 1674 (X268)

Mary Beale (1633–99) was an English portrait painter. As a woman, she received no formal artistic training, yet her talent and reputation led her to paint several prominent sitters.

Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689) was a renowned English doctor. His great achievement was to introduce an entirely new practice of medicine during the mid-17th century, which emphasised clinical observation over theoretical study. Sydenham revolutionised the treatment of smallpox and fevers in general and was the first person to recognise hysteria as a distinct disease.

Part of the exhibition 'RCP Unseen'. Explore further: