Quackery and distrust

Quackery and distrust

What varied wonders tempt us as they pass!

The cow-pox, tractors, galvanism and gas,

In turns appear, to make the vulgar stare,

Till the swoll'n bubble bursts – and all is air!

Extract from ‘English Bards and Scotch Reviewers’, Lord Byron, 1809

The stereotype of the quack doctor was widely recognised, and therefore particularly appealing to satirists.

The term ‘quack’ originates from kwakzalver, a Dutch word referring to an unregulated practitioner who sold medical cures of dubious origins, available over the counter without a doctor’s prescription. Quacks were either not educated enough or were from marginalised groups (such as women), and so could not enter medical guilds or colleges – instead they hawked homemade remedies on street corners and at fairs in loud voices likened to the cries of noisy geese.

In the past, the distinction between a legitimate, qualified medical professional and a quack practitioner was often not clear – in fact they could be one and the same. New and unproven treatments – especially radical or controversial ones – proposed by licensed practitioners were often treated with suspicion, and any practitioner was vulnerable to charges of quackery. Furthermore, even highly educated and respected doctors made errors, and their cures could be just as dangerous as a quack’s remedies. On the other hand, some quacks were well-intentioned healers with widely respected skills – a medical professional in many respects, but without the qualifications.

For satirists, quacks were not a clearly delineated group of people, but anyone they wanted to attack. Quack practitioners and their remedies were exposed and ridiculed in satirical imagery, but legitimate medical professionals with controversial ideas or treatments were in turn represented as ill-informed quacks. Characteristics of quack practitioners were often ascribed to medical professionals – and other public figures – to label them as distrustful, boastful and ignorant.

The cow-pock – or – the wonderful effects of the new inoculation!

The cow-pock – or – the wonderful effects of the new inoculation!

Engraving by James Gillray, published by Hannah Humphrey, London, 12 June 1808

PR15051

This satirical print by the political cartoonist James Gillray (1756–1815) was originally thought to lampoon English doctor Edward Jenner (1749–1823). Jenner developed a successful vaccine for the deadly smallpox virus using the milder disease of cowpox.

The smallpox vaccine was controversial because it involved injecting infected tissue from cowpox sores into healthy humans. In the image, a doctor uses a lancet and a dose of ‘Vaccine Pock hot from ye Cow’ to administer the smallpox vaccine to a frightened woman. Gillray plays on the popular but misplaced fear that the vaccine caused people to develop cow-like characteristics: a butcher grows horns, a pregnant woman produces a cow from her mouth and petticoat, and many patients sprout cows from their bodies.

This print is now thought to depict Dr William Woodville administering Jenner’s vaccine at the St Pancras Hospital in London. Woodville was in a dispute with Jenner after some of his patients died from Smallpox when he used Jenner’s vaccination technique. Although Jenner’s vaccine eventually contributed to the global eradication of the disease, in the early 19th century it was alarming, distrusted, and likened to a quack remedy.

View catalogue entry for The Cow Pock or the wonderful effects of the new inoculation

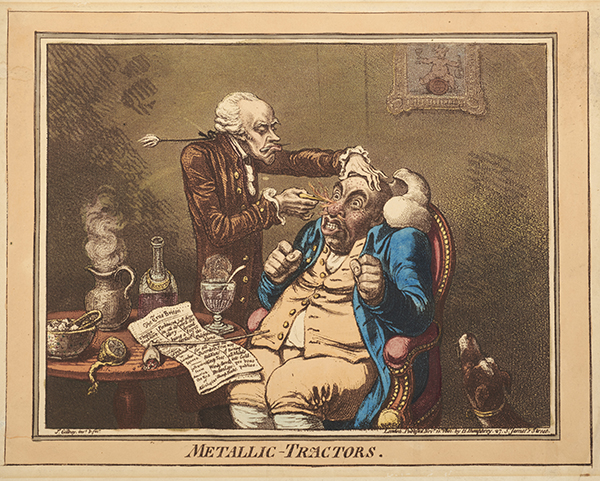

Metallic tractors

Metallic tractors

Coloured etching by James Gillray, published by Hannah Humphrey, London, 1801

2008.1/17

Scientific phenomena such as electricity and magnetism drew increasing public interest in the 18th century, and were quickly adapted into often lucrative quack medical treatments.

In this image, a patient with a bulbous, boil-spotted nose is treated with a set of ‘metallic tractors’ by a serious-faced, gurning doctor. The tractors are 9cm metal rods with a pointed end. The doctor applies them to the patient’s red nose, which shoots flames as the illness is withdrawn.

Tractors were drawn across the skin to discharge ‘galvanic electricity’ – a kind of electrical life force thought to be present in living things – into the affected part, resulting in instant, painless cures. The electricity is shown in the print, knocking the patient’s wig off and making the doctor’s hair stand out horizontally.

The exaggerated features and humorous postures of the two figures ridicule the practice and popularity of ‘tractoration’. However, we know that this print was designed as a covert – and effective – marketing ploy. The newspaper in the image refers to the tractor’s inventor, Elisha Perkins: ‘just arrived from America … Perkinism in all its Glory – being a certain Cure for all Disorders’.

Perkins’ son Benjamin supposedly commissioned James Gillray to create this print, requesting that their arrangement be kept secret and the print be sold widely. For Perkins it seems that there was no such thing as bad publicity. His tractors sold for high prices and he returned to America in 1810 after making his fortune.

Galvanic tractors

Galvanic tractors

England, 1798–1808

S42

Galvanic tractors (also called metallic tractors) exploited a trend for using electricity for medical purposes. Two rods made of different metal alloys are separated by a flat rod of a third metal, all stored in a small case. They were designed by American doctor Elisha Perkins and exported to the UK in 1797 by his son Benjamin.

Tractors were a quack treatment, promoted to cure everything from burns to epilepsy. ‘Tractoration’ – drawing the tractors across the afflicted area – was recommended for 20 minutes a day. Although many medical professionals were sceptical, tractors were popular with the public in both the USA and the UK, and they made the Perkins family very wealthy.

Accepted from Jean Symons under the Cultural Gifts Scheme by HM Government and allocated to the RCP, 2018

Part of the exhibition A taste of one's own medicine. Explore further: