Related pages

Filming Harvey: ceaseless motion brought to life

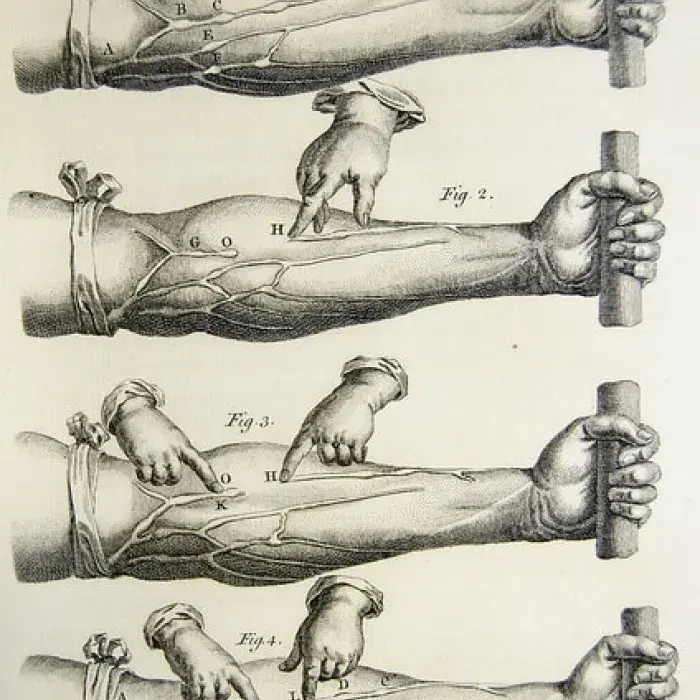

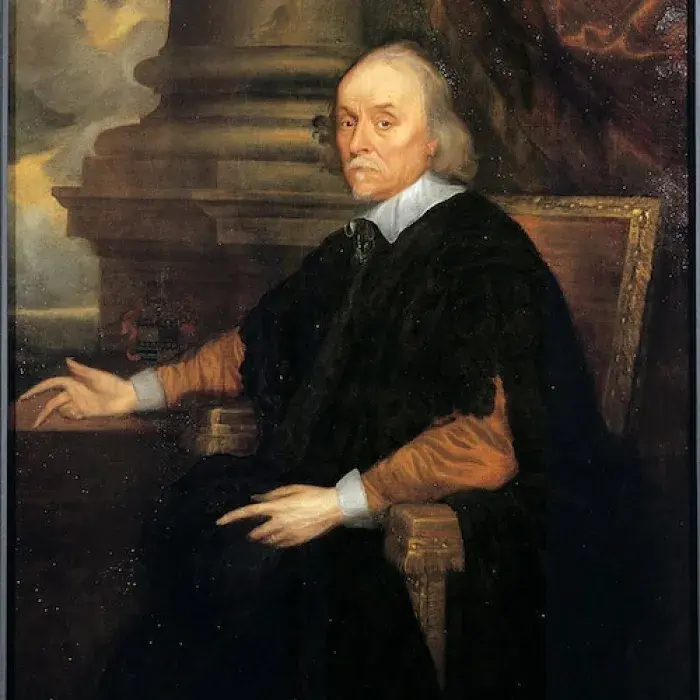

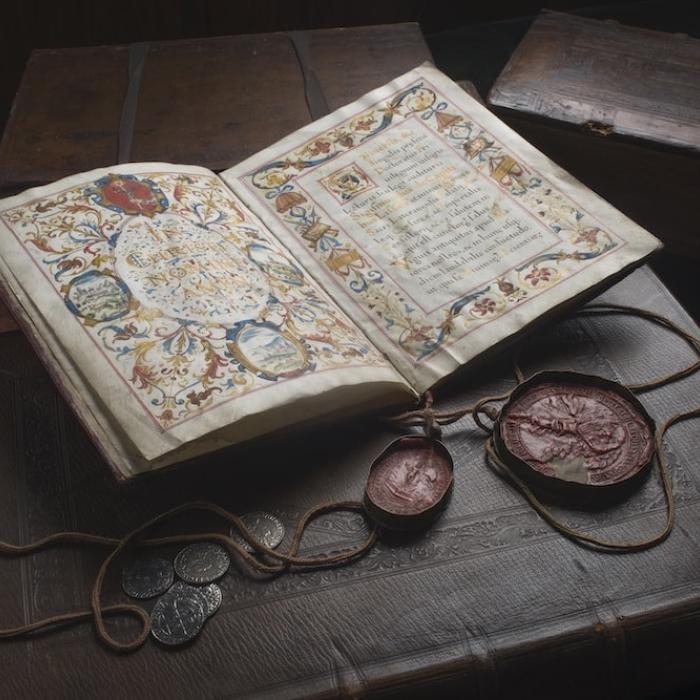

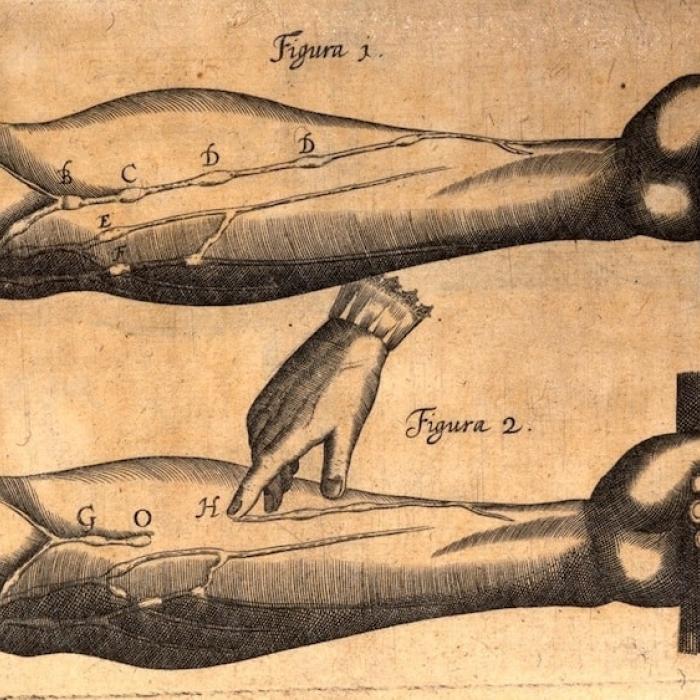

A film is being created to accompany the 2018 exhibition ‘Ceaseless motion’, which will reveal the life and work of William Harvey, RCP fellow who discovered the circulation of the blood.

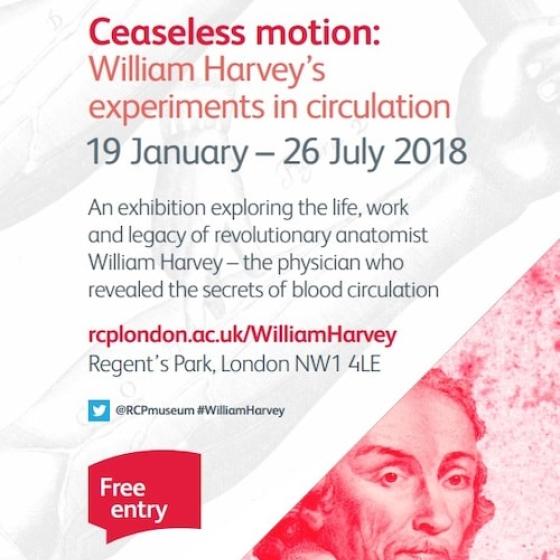

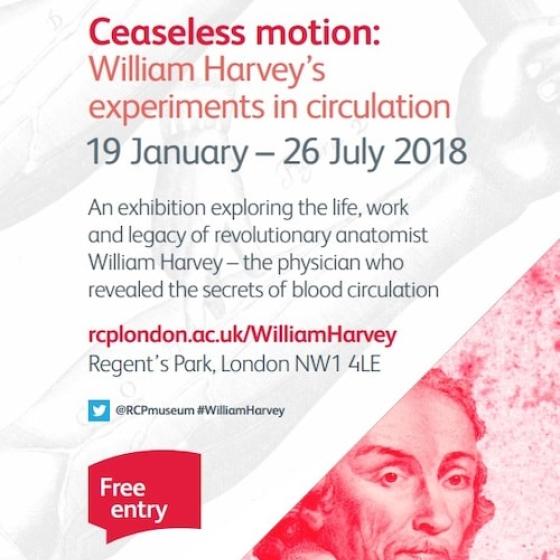

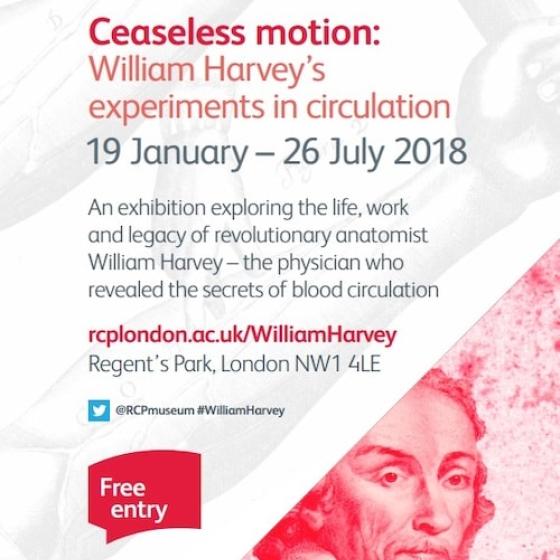

Launching the exhibition 'Ceaseless motion: William Harvey’s experiments in circulation'

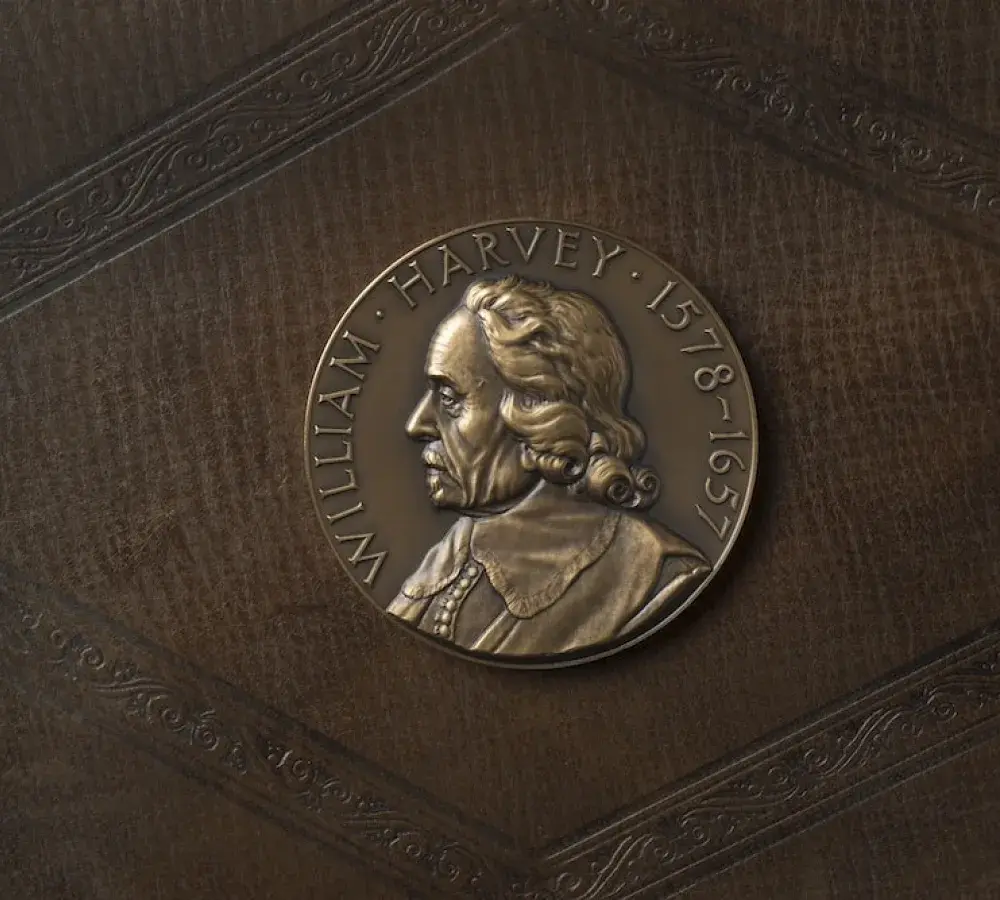

The RCP museum began its 500 year anniversary celebrations with the launch of the exhibition 'Ceaseless motion: William Harvey’s experiments in circulation', about the life, work and legacy of William Harvey (1578-1657), the physician who discovered the circulation of the blood around the body.

Courage under fire: physicians working in difficult conditions

In times of war physicians face dangers of many kinds while caring for their patients. Testimony from RCP oral history recordings records stories of courage during World War II and the Biafran War.

Harvey and the witches

William Harvey is famous for discovering the circulation of the blood around the body. He was also involved in 17th century investigations into allegations of witchcraft.

To war with William Harvey: the Battle of Edgehill

Royal physician William Harvey was present at the Battle of Edgehill during the English Civil War. King Charles I presented Harvey with a portrait of his son, Charles, as a gift.