Charles Fletcher

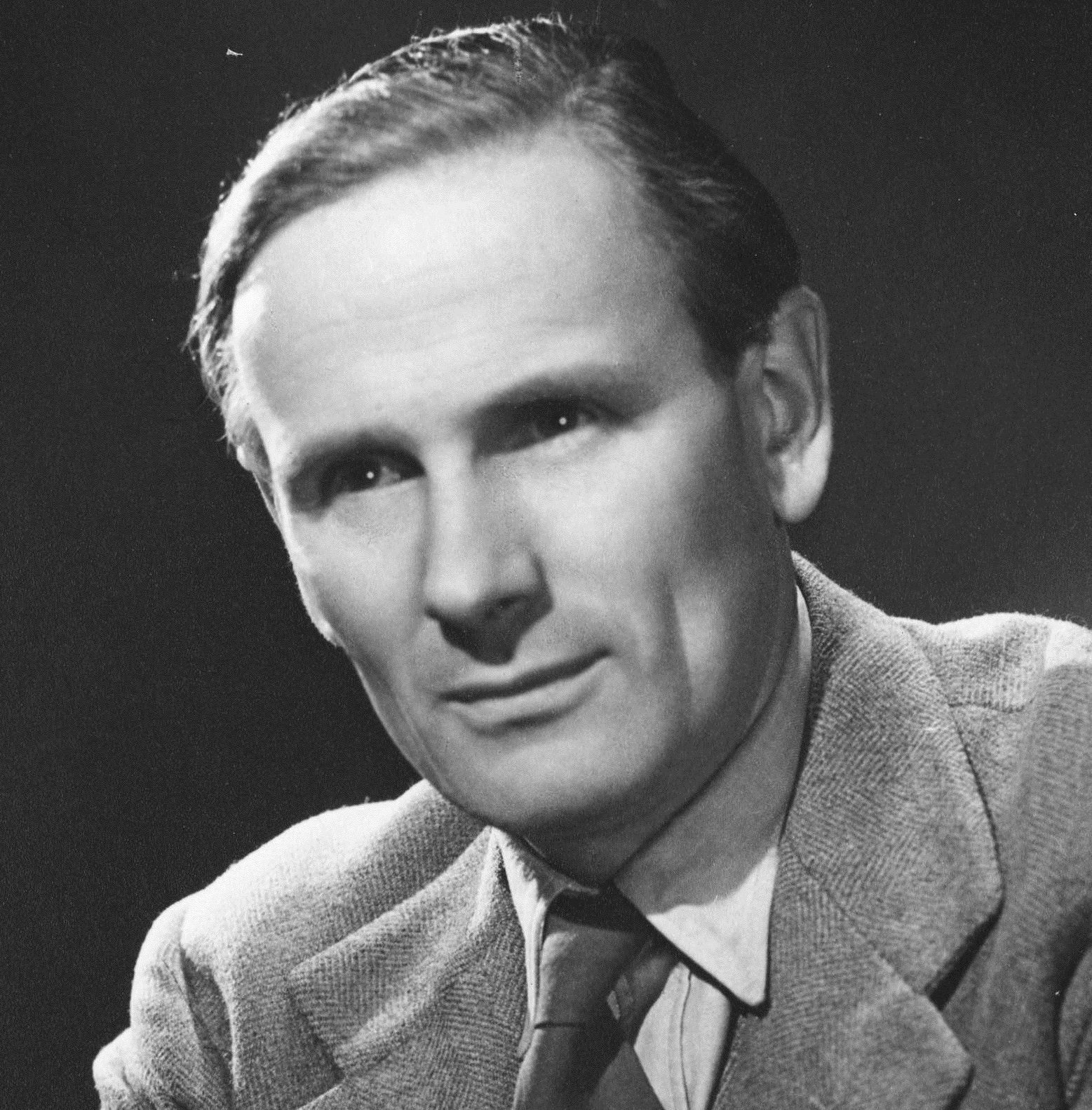

Professor Sir Charles Fletcher

In this interview he discusses Howard Florey's and Ernst Chain's work on the development of penicillin at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, Oxford, following its discovery by Alexander Fleming in 1929. Below you will find a short abstract from the interview discussing his first use of penicillin. A full biography of Sir Charles can be found on our inspiring physicians website and links the full interview of Charles Fletcher CBE FRCP in interview with Max Blythe can be found on the library catalogue.

Interview from the Medical Sciences Video Archive

Photo credit: by John Vickers, 1947 (c) University of Bristol Theatre Collection

Transcript

Charles Fletcher the first ever administration of penicillin to a patient:

Now the first thing was to see if by any chance this drug, which had been so harmless to mice, might be acutely toxic to human beings. And the remarkable thing is the first thing I was asked to do was to find someone who was dying, inevitably dying, of some disease, in whom it wouldn't really matter... if the first injection proved fatal. We wouldn't do it that way nowadays at all, but at that time it was done. And I found a very nice lady who was unfortunately dying of disseminated cancer and I asked if she would mind having an injection of a new drug that might be helpful to people, I didn't say it would help her, and she agreed to the injection. So Florey came along with an ampule of the drug, with Witts, and we went into the ward, filled this ampule with this yellow fluid, because the extract was yellow in those days from the yellow excretion of the mold from which penicillin was grown, and I got a syringe out and injected it into the vein of the patient. And about three hours later she had an acute raise of temperature, she had a rigor fever, so that showed that the penicillin at that time had a pyrogen or something that produces fever in it.

And Florey worked away in the laboratory with rabbits to get rid of this, to purify it still further and get rid of it, and then he had a substance from which he had removed the pyrogen as shown with rabbits. And then I had the job of finding out which way this penicillin could be given. Obviously we tried by mouth but it was destroyed in the stomach, we tried by the other end of the alimentary canal, by rectum, and we decided that the only thing we could do with the very scarce supplies then available was to inject it intravenously. Now, what about a patient? Well the Radcliffe infirmary like all hospitals had a septic ward and I went down there to find somebody who had a serious infection with a germ which could not be cured by other drugs but penicillin might cure, and there was a policeman there, a delightful man, who had been in having septicaemia with boils breaking out all over him, he'd lost one eye from the poison, he had boils all over him and he was in a desperate state, and we started penicillin and it was absolutely miraculous.

The next day he said for the first time that he was feeling better, his temperature came down, and so it went on for four or five days, and then the supplies of penicillin were so scarce that I used to collect his urine in the evening each day and bicycle with it over to the Dunn Laboratory where Chain and Florey would be waiting to hear the latest clinical news, and I would give them this urine and they would extract the penicillin so that the patient could have on the third day the same penicillin he'd had on the first day. But in spite of this it was necessary... on the third or fourth day the penicillin ran out and it hadn't completed curing his infection. The poor man then deteriorated and died about a week later.