As part of our season of posts about women’s history, today we welcome Kate Jarman, archivist at Barts Health NHS Trust, writing about women medical pioneers at Bart’s Hospital in London.

Barts Health NHS Trust, one of the UK’s largest acute healthcare Trusts, today employs clinicians across four major hospital sites, serving a population of around 2.5 million in the City and East London. Reflecting the wider NHS statistics, female staff account for nearly three quarters of the Trust workforce, including many of the clinicians. But the histories of the hospitals that make up the Trust the Royal London, St Bartholomew’s, Whipps Cross and Newham – and their associated medical schools, also reflect the wider story of women in medicine as one of exclusion and sometimes outright hostility. Progress has been slow, both in attitudes within the hospitals and the wider social environment: as late as 1990, Wendy Savage, first female consultant in Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the Royal London noted that ‘One of the problems with medicine is that it is not an ordinary full-time job which most women can manage as well as the responsibility of running the house and the family, which still tends to fall on them’ – although today, initiatives like the Barts Health Women’s Network support continued efforts to provide equality of opportunity within the pressurised working environment of the modern NHS.

At the oldest of the Trust’s hospitals, Bart’s, and at The London (as it was known until 1990), where attitudes were often conservative and resistant to change, barriers to women’s entry into the medical profession were overcome through social and political circumstance as much as through the efforts of the early women who attempted to challenge the male dominance of the profession. The stories of Elizabeths Blackwell and Garret Anderson, both discussed in the RCP’s This vexed question exhibition, are fairly well known. Blackwell, who had graduated in medicine in America, and wished to complete her training by walking the wards at a London teaching hospital, received a warm response from James Paget, surgeon and Warden of St Bartholomew’s Hospital Medical College, and was given permission in 1850 by the hospital’s medical committee to attend as a student in the wards and other departments. Although Blackwell later wrote that ‘at first no one knew how to regard me’, she was generally well received, and completed her studies without impairment, though with conditions – no entry to the syphilitic wards, or to the midwifery wards following the instruction of Charles West, physician-accoucher, and dissections to be carried out separately to her male counterparts.

The experiences of the first woman to study at the London Hospital Medical College, Elizabeth Garrett (later Garrett Anderson) were more challenging, despite the fact that like Blackwell, she had already undertaken most of her training (a condition seen by Paget as essential for the admission of women students). Inspired perhaps by her experiences seeing Blackwell speak, she managed against some opposition to gain a place walking the wards at the Middlesex Hospital, and having privately obtained a certificate in anatomy and physiology, she was admitted in 1862 by the Society of Apothecaries who, as a condition of their charter, could not legally exclude her on account of her sex. Her experiences at the London, where Mr LS Little, orthopaedic surgeon, had agreed to take her on as a pupil for 6 months, were typical of her efforts to further her studies. Attending for the first day in February 1864, Garrett found herself ‘with nothing definite to do and the consciousness of being under a fire of criticising eyes; nurses, patients, and students’. She was able to finish her six months, and a further six months instruction in practical midwifery, but her tutors came under pressure from her fellow students on a number of occasions to stop teaching her. She finally gained her Licentiate of the London Society of Apothecaries in 1865.

Despite (or perhaps motivated by) the efforts of pioneers like Blackwell and Garrett, the London teaching hospitals moved to actively prevent women from gaining the credentials that would allow them to become practitioners, and those who attempted to follow in their footsteps are much less well known. At both Bart’s and the London, opposition was coordinated by students rather than staff, with the aim, according to Frances Power Cobbe, writing in 1881, ‘to keep ladies out of the lucrative profession of physician and crowd them into the ill paid one of nurses’.

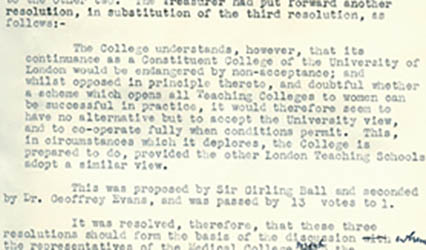

Ellen Colborne, permitted to join the medical college at Bart’s in 1865 and ‘attend the lectures of such members of the staff as may be disposed to allow of her attendance’, met with a petition ‘signed by almost every man in the College’ hastily drawn up following a meeting of the students to see ‘what measures should be taken to prevent if possible, the lady from becoming a student’. Colborne continued to attempt to attend lectures, although several teaching staff attempted to dissuade her, having seen the uproar that greeted her entry to the lecture theatres. At one such lecture on surgery, William Savory, the lecturer, asked the students to vote on whether they wanted him two continue – only two voted to carry on ‘under the circumstances’. Despite threatening legal action against the college, and refusing to take back her fees, Colborne could do little faced with such opposition – lectures were simply cancelled when she attended. She eventually withdrew in January 1866, and unfortunately it appears that she never achieved her goal of qualifying as a doctor. She was the last woman to be admitted as a medical student at Bart’s until 1947, when the first cohort of female students were admitted shortly before the hospital was forced to become co-educational by the University of London’s ruling on all London medical schools.

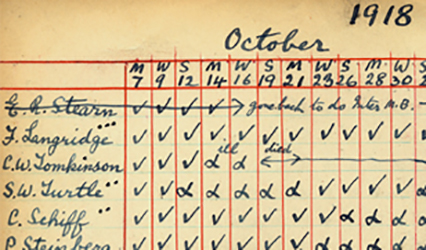

At the London, the shortage of male staff caused by the First World War did bring change, though only temporarily. John Ellis writes that women were the third choice to fill this gap, after the options of retired ‘Old Londoners’ and Americans had been exhausted. Professor Wright, Dean of the Medical College, first presented a case to the University of London for the admission of women in 1917, but it was not until May 1918 that the decision was taken that women should be admitted as students. Unlike male students, they were made to wear white coats, but it does seem that the early female students were accepted with little comment or alternative provision being made. Pieces entitled ‘Notes from the Women’s Common Room’ appeared in the hospital gazette and they took part in the social life of the medical school. However, numbers of women enrolling remained low, with only 65 women in total being admitted in the student cohorts that commenced until the decision was reversed in 1922 (between 10 and 20% of the entrants in each year). Although, like Bart’s, the London did not accept women again until after the Second World War, the episode did lay the foundations for a female presence on the London Hospital medical staff, and several of the post-war cohort went on to have prestigious careers, including Dorothy Russell, the first woman in Western Europe to be appointed to a chair in Pathology, and Professor of Morbid Anatomy at the London from 1946.

But for me, the stories of the women clinicians at the smaller hospitals that were part of the Trust and its precursor health authorities are perhaps more compelling, if often lost to history. Barts Health NHS Trust Archives hold the records of over 30 current and former hospitals, and although, as in many archives, the surviving records are often only partial, it is clear that women were accepted onto the medical staff of smaller, less ‘prestigious’ hospitals than Bart’s and the London earlier and with less opposition.

At Whipps Cross Hospital, for example, a former poor law union infirmary, a photograph of nursing and medical staff of the hospital taken c1910 shows what appears to be a female doctor among the medical staff in the middle row of the group. Whether the decisions at hospitals like Whipps to recruit women (though not train them – Whipps was not a teaching hospital) were due to necessity, more progressive social attitudes, or both, is unfortunately unclear, since in many cases the records that might shed light on these decisions, or on the names of the women, no longer survive in the hospitals’ archives.

However, there is much still to be uncovered about the history of medical women in hospitals in the City and East London, and we welcome researchers working on this area.

- Find out more about Barts Health NHS Trust Archives and how to access them .

- Find out more about Ellen Colborne and Elizabeth Blackwell’s experiences in a display at St Bartholomew’s Hospital Museum on until early 2019.

Kate Jarman, Trust Archivist, Barts Health NHS Trust

Sources for quotations in the post:

- Blackwell E. Pioneer work in opening the medical profession to women: autobiographic sketches. London: Longmans, Green, & Co, 1895: 164.

- Cobbe FP. Medicine and Morality. Modern Review 1881;11:323.

- Garrett E. Correspondence quoted in L Garrett Anderson, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. London: Faber and Faber, 1939: 111.

- Minutes of meetings of the Medical Officers and Lecturers, St Bartholomew’s Hospital Medical College, 1850–1869, 14 October 1865. SBHMS/A/11/4, St Bartholomew’s Hospital Archives.

- Photograph of a group of nursing staff, with matron, Miss Letitia S. Clark and members of the medical staff in the grounds of Whipps Cross hospital, c.1910. RLHWX/P/4/3, Royal London Hospital Archives.

- Savage W. Women in Medicine – The London Hospital's Contribution. Text of a lecture given for the 250th Anniversary of the London Hospital at Whitechapel. RLHLH/X/168/7, Royal London Hospital Archives.

The exhibition This vexed question: 500 years of women in medicine opened on 19 September 2018 and runs until 18 January 2019.