Until 10 July 2017 The Recipes Project is hosting a virtual conversation exploring what a recipe is by inviting people to ask questions like ‘How do we know one when we see one?', 'What is their structure?', 'What functions do recipes serve?', 'How are they shared and passed on?', and 'Are they a set of instructions, a way of life, or a story?'.

What is a recipe?

So today we’re exploring the question ‘what is a recipe?’ by looking at one medical preparation recorded in three different sources.

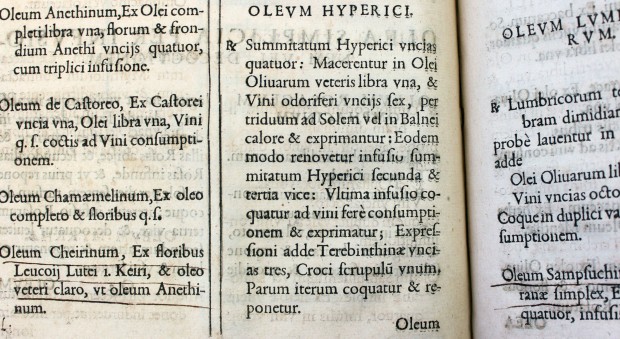

In 1618 the College of Physicians, as the RCP was then generally known, published the first edition of its Pharmacopoeia Londinensis, the book which stipulated what medicines apothecaries were allowed to dispense, and how they should be made.

Notable by their absence are explanations of the preparations: the Phamarcopoeia Londinsensis does not describe the effects or recommended uses of any of the medicines contained within, and deliberately so. It was intended for elite audiences: the physicians who prescribed the remedies and the apothecaries who made up and dispensed them. This book was not intended for use by the general public.

The Pharmacopoeia is divided into sections for different types of medicines: waters, syrups, ointments, powders, pills and so on. In the section on oils, infusions of many different plants – and some other substances such as myrrh – are listed. One of these uses St John’s wort, Hypericum perforatum, a plant still used as a herbal remedy today.

The Pharmacopoeia instructs that Oleum hyperici ( oil of St John’s wort) should be made by crushing four ounces of the tops of the plant with a pound of olive oil and six ounces of fragrant wine, heating them for three days in the sun or a hot bath and topping up as needed, adding three ounces of terebinth, and a scruple of saffron. ‘Terebinth’ refers to the tree Pistacia terebinthus, and quite possibly to its resin commonly known as turpentine.

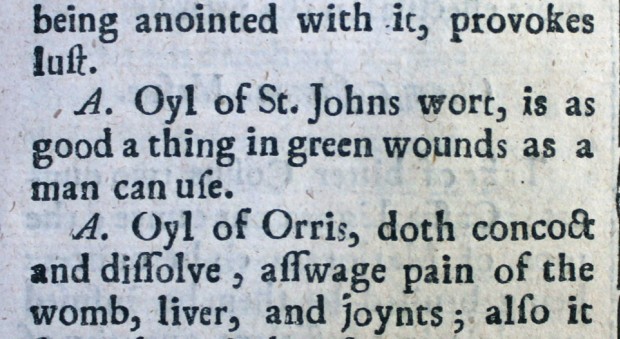

True to its principles, the Pharmacopoeia does not state the qualities or uses of Oleum hyperici. The apothecary John Quincy (d.1722), writing in his 1718 Compleat English Dispensatory (1718), explained that this oil had some use as it was ‘warm and penetrating’ making it ‘of use in cold pituitous Tumours, and likewise in Rheumatick and Arthritick’. He also notes it is often used for bruises. Another medical writer, the herbalist and astrologer Nicholas Culpeper (1616–1654), does not mention those uses for oil of wormwood. He instead writes that it’s ‘as good a thing in green wounds as a man can use’.

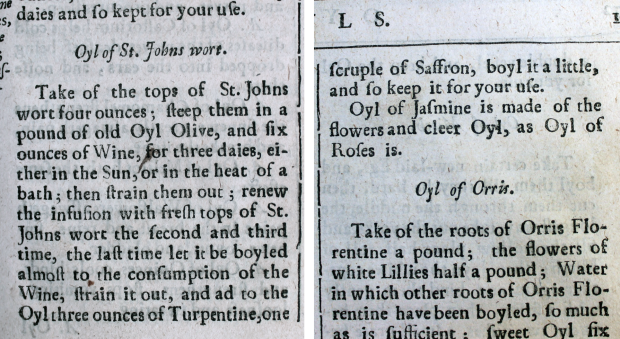

Nicholas Culpeper provides us with the second comparator in this examination of recipes. In 1649, much to the College of Physicians’ chagrin, Culpeper published an English translation and expansion of the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis under the title A physical directory, or A translation of the London Dispensatory made by the Colledge of Physicians. Culpeper’s book – which ran to several editions – includes not only the ingredients and method from the Pharmacopoeia, but also explanations of the effects of the remedies listed, complete with an index of complaints and one of ingredients.

Here we see the same remedy as above: Oil of St John’s wort. Culpeper’s version is a clear translation of the Latin of the Pharmacopoeia, specifying turpentine directly, rather than using the slightly ambiguous (at least to the modern reader) ‘terebinth’.

Recipe circulation

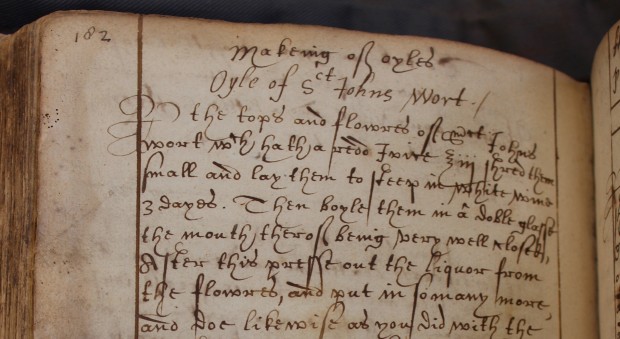

Our archive collections included several early modern recipe books. These handwritten compilations usually include a mixture of culinary, medicinal and cosmetics recipes, sometimes even all on one page. Sarah Wigges’ recipe book, dated 1616, contains mostly medical recipes. A section of culinary recipes at the end appears to have been written by ‘Mo. Wigges’, Sarah Wigges’ daughter. Several recipes in the collection are attributed to other sources, including Andrew Boorde’s Breuiarie of health, raising the interesting question of recipe circulation.

Oil of St John’s wort makes an appearance in a section of Wigges’ collections dedicated to medicinal oils. Wigges’ recipe is very similar to those found in the Pharmacopoeia and in Culpeper:

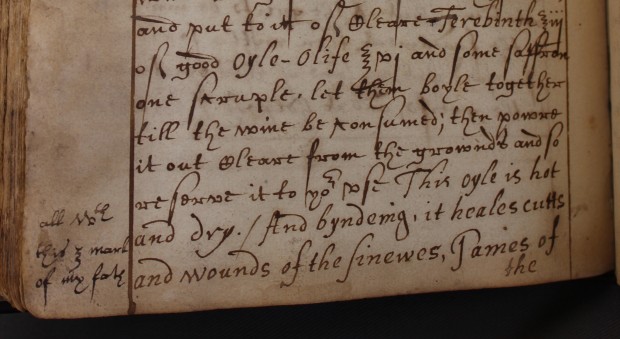

the tops and flowres of [Saint] Johns wort w[hi]ch hath a redd Juice [ounces] iii shred them small and lay them to steep in white wine 3 dayes. Then boyle them in a doble glasse the mouth therof being very well closed, After this presse out the liquor from the flowres, and put in so many more, and doe likewise as you did with the fyrst, and then presse out the liquor from them, and so doe 3 or 4 times, every time takeing new and fresh flowres. And if the wine be deminished, you may add a little more to itt: Then take the wine being strayned from the flowres, and put to itt of cleare Terebinth [ounces] iii of good Oyle-Olife [ounces] vi and some saffron one scruple. let them boyle together till the wine be consumed; then power it out cleare from the grownds and so reserve it to yo[u]r use.

Writing in a different handwriting adds a comment about the qualities and uses of the oil, suggesting uses mirrored by both Quincy and Culpeper:

This oyle is hot and dry. And byndeing, it heales cutts and wounds of the sinewes, Paines of the hipps, thighs, and bladder and provokes Urine.

Which of these three would you consider to be a recipe? There’s little difference in the content of each recipe, but the context here is key. Sarah Wigges’ book looks and feels like a collection of recipes and advice for domestic use. The instructions include more information about equipment and method than do the two published sources. Details such as shredding the flowers into small pieces, boiling the liquid in a double glass and so on provide a more comprehensive account of how to make the medicine, usable by someone perhaps with little familiarity with the process. The accounts in the Phamarcopoeia and from Culpeper, in contrast, feel abbreviated. They have the air of an aide memoire for someone already familiar with the techniques involved.

A note in the margin of the Wigges recipe might also colour our view. Near the bottom of the page is written ‘all w[i]th this ℥ mark of my fath’. Does this indicate that the recipe came from the writer’s father? Or is it saying something else that we haven’t deciphered? Do indications of provenance – certainly a popular part of recipe writing and collection to this day – contribute to our notions of what is, and isn’t, a recipe?

Katie Birkwood, rare books and special collections librarian

Presentations on 'What is a recipe' can be found via The Recipes Project blog, and using #recipesconf on Twitter and Instagram. Learn more about the RCP’s collections, and follow @RCPmuseum on Twitter and @rcpmuseum on Instagram.