In 1642 the painter William Dobson (1611–1646) was summoned to Oxford by King Charles I. The king wanted Dobson to paint a portrait of his eldest son Charles, the Prince of Wales and the future King Charles II. The portrait was intended as a memento for its recipient, William Harvey (1578–1657). But why did the King wish Harvey to have a portrait of his eldest son? What had Harvey done to deserve such an expensive gift? The answers all lead back to one dramatic moment in British history: the Battle of Edgehill.

The Battle of Edgehill

On the 22 August 1642 Charles I raised his battle standard above the walls of Nottingham castle, setting royalist against parliamentarian and beginning nine years of brutal civil war all across the British Isles. Two months later, after amassing a large army, the King was marching towards London when he was surprised by the parliamentary army, led by the Earl of Essex, near the town of Kineton in Warwickshire. Neither army was expecting to meet the other, so each quickly made preparations for battle. The next day, Sunday 23 October 1642, the two sides faced each other at a placed called Edgehill.

The two sides were closely matched, with King Charles fielding 12,500 troops and 16 cannon, whilst the parliamentarians numbered approximately 15,000 troops and seven cannon. The fighting began at 2pm and continued for two and a half hours, until sunset at 4.30pm. Even though the fighting was fierce, neither side could claim victory, leading to stalemate and the withdrawal of the parliamentary army to Warwick. But enough had been done to slow the King’s advance to London, and he never made it to the city, instead making Oxford the Royalist capital for the duration of the war.

The Battle of Edgehill was a missed opportunity, as a decisive victory there for either side may have brought a swift resolution to the war.

Why was William Harvey there?

An English Civil War battlefield is not the first place you’d look for the eminent anatomist and doctor of physic William Harvey. You’d be far more likely to find him delivering the Lumleian lecture at the Royal College of Physicians, or overseeing the care given to patients at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. So what was Harvey doing at the Battle of Edgehill?

The answer lies with King Charles I. By 1642 Harvey was employed as the King’s physician-in-ordinary; in other words, his chief physician. As the king travelled the country, so Harvey followed along with him. This is why we find William Harvey at Edgehill with the King on the 23 October 1642.

What did Harvey do during the battle?

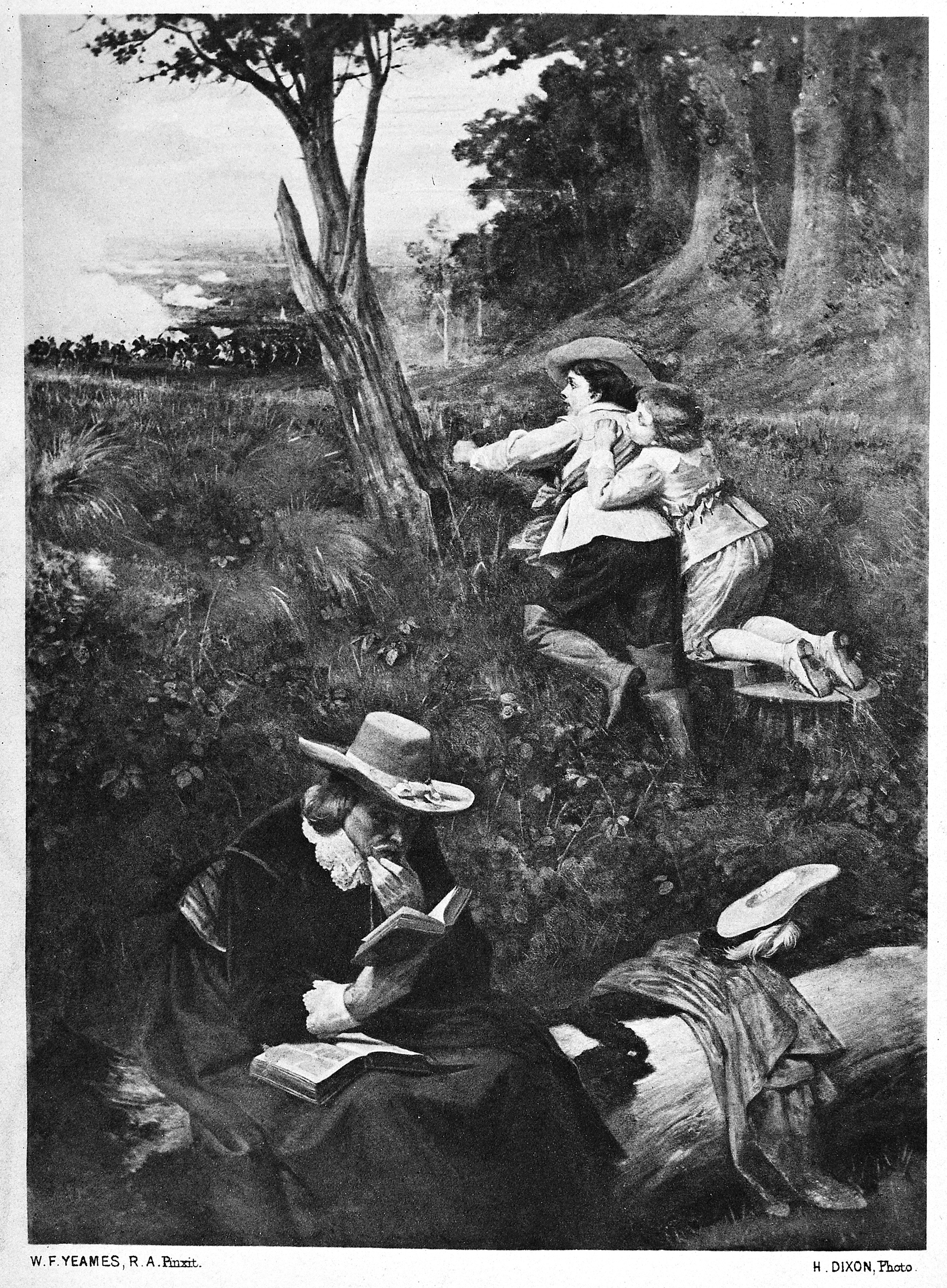

Although William Harvey was present at the battle, it is safe to say that he wasn’t charging into the fray, sabre in hand. Being part of the King’s entourage, Harvey was tasked with keeping the two young princes, the 12 year old Charles and 9 year old James, safe from harm. The princes were indeed kept safe, with only one near miss. During the opening salvos of artillery fire, Harvey recounted later to his friend John Aubrey that ‘a bullet of a great gun grazed on the ground near him, which made him remove his station.’ This was as close to the action as Harvey got, and he spent the majority of the battle trying to read his book and protect the eager young princes.

What happened to Harvey after the battle?

As the fighting came to a close, both sides camped on the field of battle. During the aftermath Harvey helped to care for the wounded. Again, talking to John Aubrey, Harvey recounted the case of Sir Gervase Scrope

[Scrope] was dangerously wounded there [Edgehill], and left for dead amongst the dead men, stripped; which happened to be the saving of his life. It was cold, clear weather and a frost that night; which staunched his bleeding, and about midnight, or some hours after his hurt, he awaked, and was fane to draw a dead body upon him for warmth-sake.

Sir Scrope was later found on the field by his son and ‘recovered by the immortal Dr William Harvey.’

As the events of the Civil War played out, Harvey’s fate was tied to that of King Charles I. Harvey was unable to return to London to continue and remained in Oxford, where the King appointed him Warden of Merton College in 1644. A more severe consequence of his royalist association happened when Harvey’s home in London was raided and his work De insectis and other papers were destroyed or stolen. Aubrey described the loss of these works: ‘He [Harvey] could never for love nor money retrieve them or hear what became of them and said “twas the greatest crucifying to him that ever he had in all his life”.’

Harvey’s gift from the King

The portrait King Charles I gave to William Harvey is full of meaning and representations of the Battle of Edgehill. The young prince is represented in civil war era armour, attended by a younger boy who may be his page, or perhaps his younger brother James, Duke of York, and future King James II. In his right hand Prince Charles holds a commander’s baton over the image of captured colours and the head of medusa, representations of both the victory and horror of battle. In the background a cavalry skirmish is taking place, alluding to the superior royalist cavalry and their successful charge into the parliamentarian flanks during the Battle of Edgehill. The portrait was passed down through the generations of William Harvey’s brother Eliab, until it was sold to the National Portrait Gallery of Scotland in 1935.

For Harvey, this portrait may have been of some comfort to him in his later years. It is a pity that, for a staunch royalist such as Harvey, he died in 1657 and so did not live to see the monarchy restored and the young Prince Charles return to England in 1660 as King Charles II.

Matthew Wood, exhibitions officer

The exhibition Ceaseless motion: William Harvey’s experiments in circulation is open 9am–5pm, Monday–Friday, until 26 July 2018.