Our pop-up exhibition Under the skin: illustrating the human body ran from 1 February to 15 March 2019.

The exhibition ran as part of the Thinking 3D interdisciplinary research project, exploring representations of three-dimensionality since the time of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). The main aim of the RCP exhibition was to explore the ways in which anatomists, artists and printers have met the challenge of representing the three-dimensional human body on a two-dimensional page.

It’s been an opportunity to display some of the most spectacular images from our library and archive collections. Some of the bodies illustrated in this exhibition are individual, identifiable people. Other images are generalised or idealised, based on multiple bodies.

How the anatomist or artist depicts a body greatly influences how we react to their illustration, and how we feel about the person represented. Clinical drawings can appear detached and impersonal, concealing both the dissection process and the once-living subject. Others emphasise the visceral details of the body, sometimes making it appear alive again, provoking feelings of disgust, pity and curiosity.

Some of the pictures are portraits of identifiable people, treating facial features and hair styles with care. Others are idealised representations of anatomy, based on experience of multiple dissections and on earlier images. Some treat the body with respect and kindness, whereas others seem to positively revel in the horror of dissection.

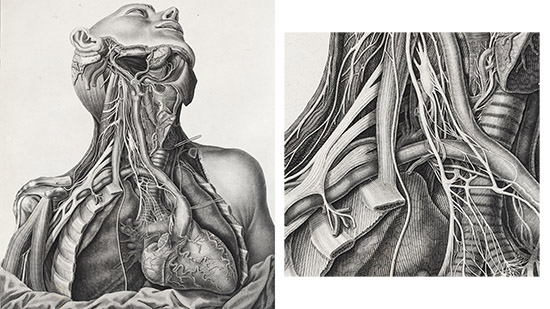

The lead image from the exhibition, Antonio Scarpa’s analysis of the nerve supply to the heart is a masterpiece of engraved illustration, with precise lines used in combination to depict the various textures and structures inside the chest.

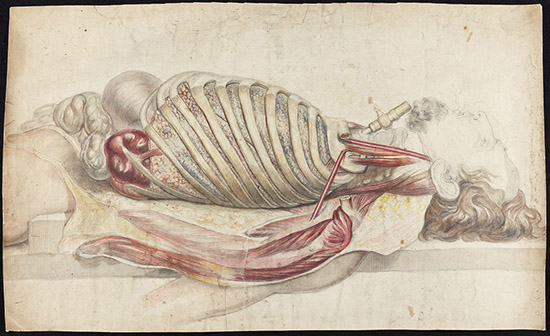

Francis Sibson’s pencil and watercolour drawing of the human lungs and internal organs creates a vivid impression of the post-mortem examination at St Mary’s Hospital, London, where he worked. As well as carefully representing the human tissues and the dissecting table, Sibson draws a portrait of a man, showing his face and hair in detail. We have several dozen of Sibson’s drawings in the RCP archives, and many of the shown similar levels of attention to the individual faces of the subjects.

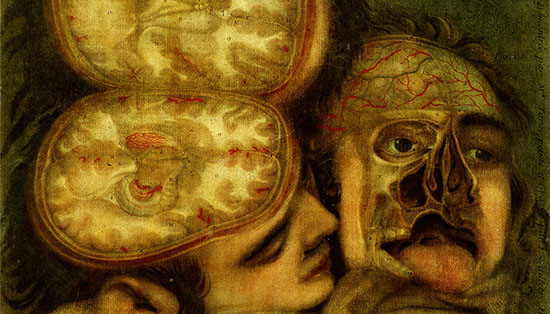

Jacques Gautier D’Agoty also portrays his anatomical subjects as if in portraits, but his approach is altogether more alarming to observe. Gautier wrote that the key to making anatomical illustrations accessible was for the artist to try to ‘render death agreeable’. In this technologically advanced colour print, two heads are nestled against each other as if in an intimate embrace, making the anatomical disfigurement of their faces all the more stark.

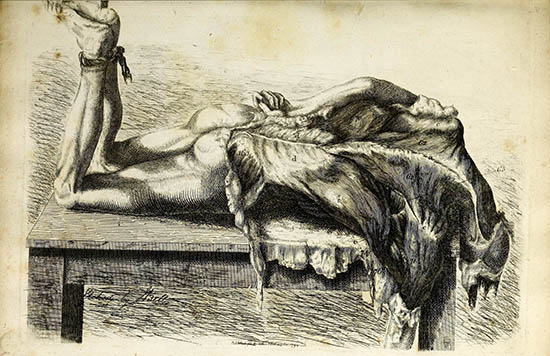

In his illustrated books, surgeon and anatomist Charles Bell strove to represent the realities of the dissecting room to medical students, rather than creating an idealised impression of a clean and neat, context-less anatomised body. This illustration of the muscles of the back seems to owe more to gothic horror than to ‘science’. The flesh of the body appears to drip towards the floor, and the bound feet suggest execution or torture. The use of etching allowed Bell to use loosely controlled, flowing lines, which create a feeling of unsettling movement. The image is very dark, and the details of the muscles – the subject of the picture – are not visible.

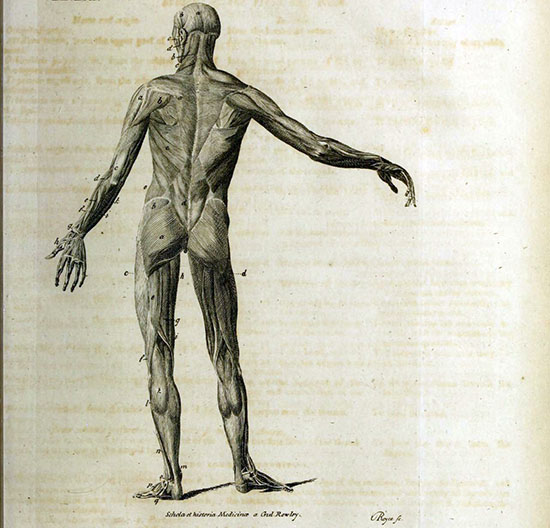

This image from a general introduction to medicine published just 9 years later shows the same muscle groups. However, it does not evoke the same sense of horror. This dissected body stands isolated in space. It is intended to instruct the viewer, without any distracting context or background. With its functional, scientific appearance the image is far removed from any living person or people who were dissected.

In most cases, the people depicted in these anatomical illustrations did not give their consent to be posthumously dissected and represented in this way. Bodies were obtained legally and illegally from the gallows or from workhouses, but were also taken unlawfully from hospitals, poor houses and graveyards.

The exhibition Under the skin has provided the opportunity to revel in the anatomical and artistic mastery behind famous and lesser-known medical illustrations, but it’s also been a chance to reflect on the human realities behind these iconic images.

Katie Birkwood, rare books and special collections librarian