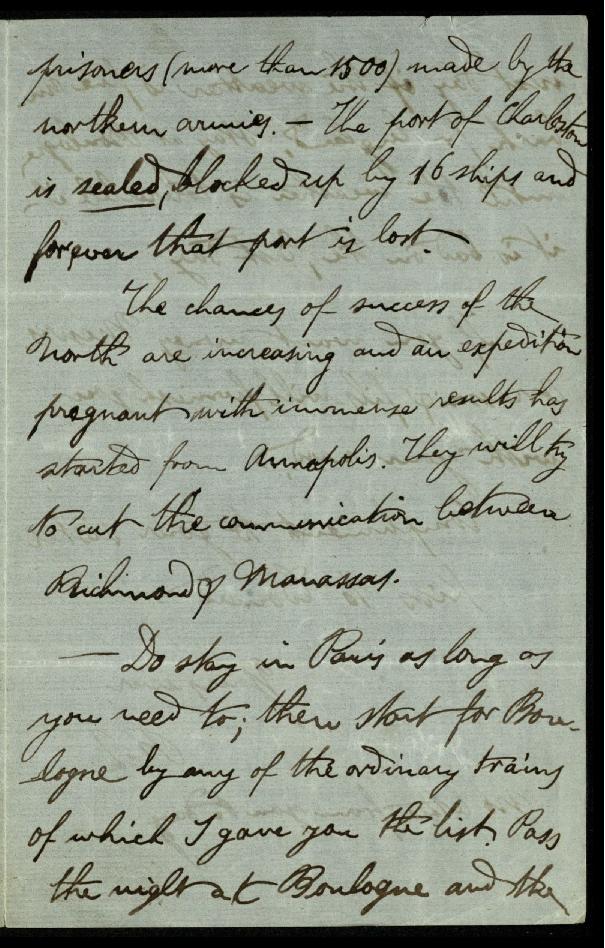

‘The chances of success of the north are increasing and an expedition pregnant with immense results has started from Annapolis. They will try to cut the communication between Richmond & Manassas.’

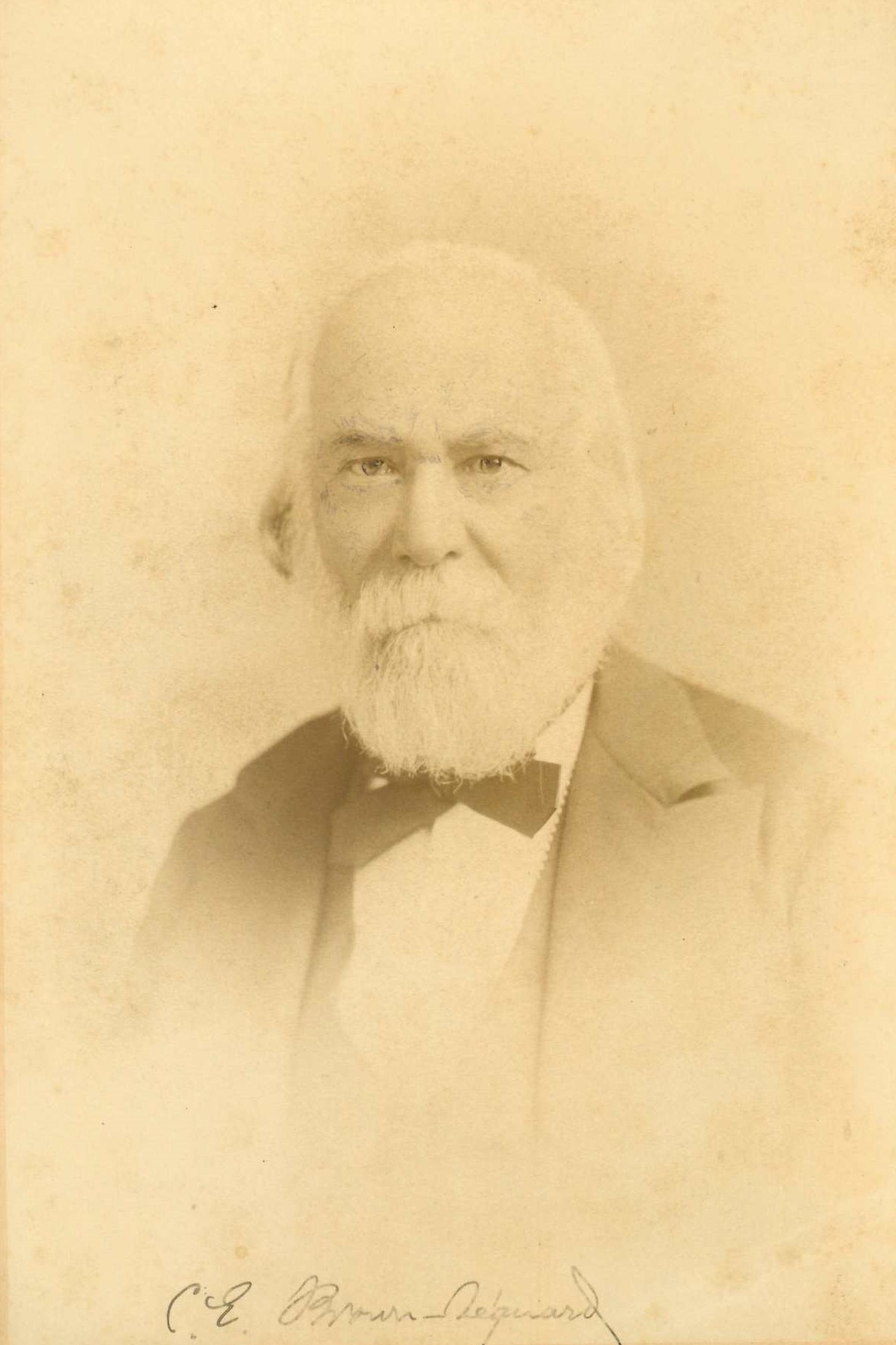

This is how Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard (1817-1894) excitedly described the latest developments in the American Civil War in a letter to his wife Ellen in June 1863 (MS977/38). Édouard was born in Mauritius but was living in London at the time, working as a physician in private practice and at the recently opened National Hospital for Nervous Diseases. Many of his RCP colleagues took an interest in the events unfolding across the Atlantic, but Édouard had a particularly personal connection to the political situation in the United States.

Eight years earlier Édouard and Ellen lived in Richmond, Virginia, where he lectured in physiology at the medical school. Édouard had not been universally popular among his colleagues or students. His work involved experimenting on animals without anaesthetic. The lab in which he kept the animals and carried out his research was in the basement of a building in which lectures took place, and in which several students lived. The shrieks and howls of animals in pain rang through the building at all hours of the day and night.

Édouard also experimented on himself, to the particular dismay of fellow lecturer, William Taylor. Taylor once discovered Édouard unconscious on the floor of his lab, his skin completely covered in fly paper varnish, which had almost suffocated him. Taylor saved Édouard’s life by sandpapering him from head to toe, but the incident convinced him his colleague was a ‘crank’. At dinner, Taylor was revolted to observe Édouard regurgitate his food into his mouth and re-chew it, like a cow chewing the cud. Édouard explained that repeated extraction of his own stomach juices using a sponge on a string had weakened his lower oesophageal sphincter, meaning his food often returned up his throat in this bovine way. The explanation did not help to restore Taylor’s appetite.

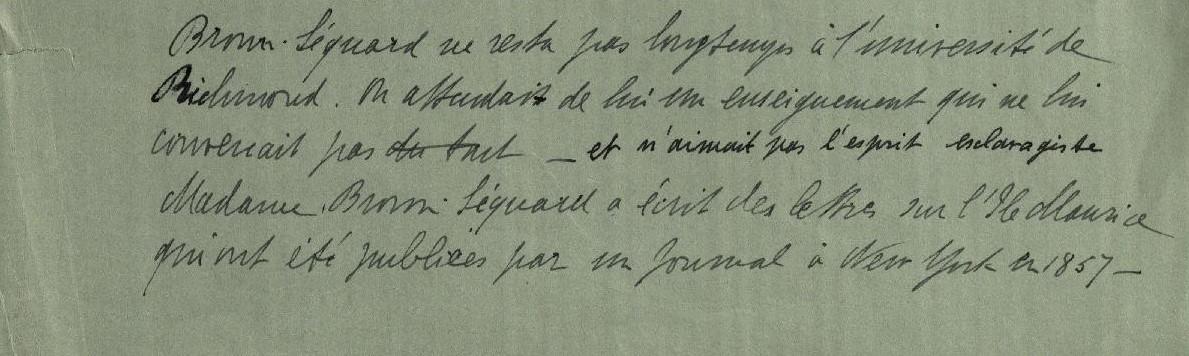

Neither Édouard nor Ellen enjoyed their time in Virginia. In a letter to her family, a copy of which is held in the RCP archives, Ellen wrote that Édouard was depressed, and that she longed to return to Mauritius where they had friends, and where, she implied, they were shown the respect she felt they deserved. She also added, albeit apparently as an afterthought in the version of the letter the RCP has, that Édouard ‘did not like the spirit of slavery’ (‘n’aimait pas l’espirit esclavagiste’, MS976/9). Other contemporaries of Édouard’s confirm that, in contrast to Ellen’s rather lukewarm expression, Édouard was passionately opposed to slavery, which was then still practiced in Virginia, and used his position to speak out in favour of abolition. Indeed, while he had been living in Paris in 1848, Édouard had fought in the revolution to overthrow the French monarchy (MS999/7, p48), an action he hoped would lead to the end of slavery throughout France’s colonies. His efforts were vindicated as the new French government abolished slavery on 4 March 1849.

In Virginia, those who were hostile to Édouard’s political views began to use perceptions of his ethnic background to undermine him. Édouard had been born to an Irish American father and a French Creole mother. As far as he knew he had no African ancestors, but had always spoken with pride about his great great grandmother, who was from the Malabar coast of India. His friends commented that he must have inherited his black hair and dark complexion from her. However, his enemies now encouraged the misconception that Édouard was of African and European ancestry. In the American South, where race was such an explosive issue, the perception of Édouard’s ethnic background, coupled with his anti-slavery views, made it difficult for him to keep his job at the medical school. Despite publishing a groundbreaking and celebrated thesis on the spinal cord during his time there, Édouard felt compelled to leave the college in 1855, after only a year.

We do not know exactly how or when Édouard’s views on slavery developed, but we do know that enslaved people worked in his childhood home in Mauritius. In fact, when slavery was finally fully abolished in British colonies in 1836, Édouard’s mother Charlotte received the equivalent of about £30,000 as ‘compensation’ from the British government. It was this money, made from slave ownership, that had paid for Édouard and his mother to emigrate to Paris and for him to study medicine.

Édouard’s family were relatively wealthy, but before he was born they had, along with the other residents of the Mauritian capital Port Louis, suffered great losses when much of the city was destroyed by fire in 1816. Crops and supplies were decimated, and to protect his pregnant wife and their compatriots from the encroaching famine, sea captain Edward Brown, set sail on a mission to secure food for the stricken island. Brown acquired a shipment of rice in Madras (now Chennai, India), and he and his crew began the voyage home. They were never heard from again. Over the years, several rumours developed regarding the ship’s disappearance, including that it had been boarded by pirates who had forced Captain Brown to walk the plank. However, by far the most likely explanation was that the ship had been wrecked by a cyclone in the Indian Ocean. Charlotte Brown (née Séquard) had lost her home and her husband, and was facing unaccustomed hardship; her only comfort was the birth of her son in April the following year.

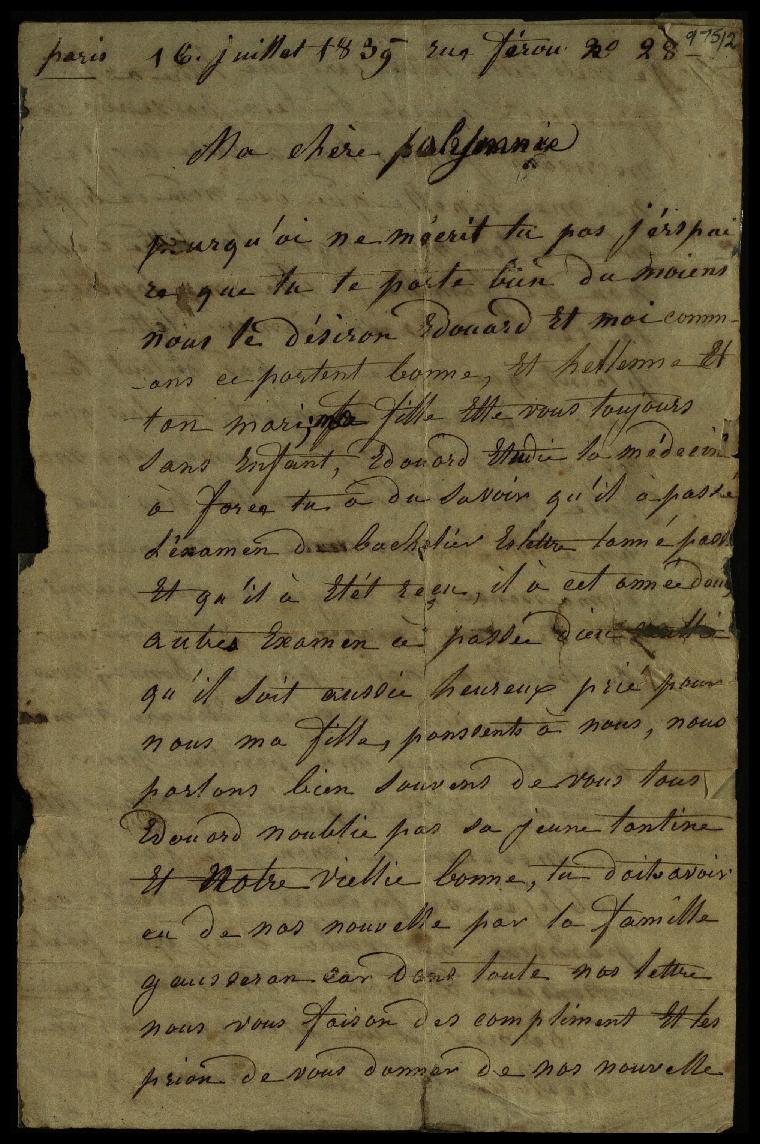

Édouard was an intelligent child, who developed passions for nature and the arts. He excelled at school, but if he was going to get a university degree, he would have to leave Mauritius. The slaveowner money his mother acquired in 1836 afforded them both the chance to do just that. The RCP has in its archives a letter written in Paris by Charlotte Brown, addressed, possibly, to the adult daughter of the enslaved woman who had worked as a maid and nanny in the Brown household in Mauritius (MS975/2; see also page 15 of Celestin, Louis-Cyril (2013), Charles-Edouard Brown-Séquard – the biography of a tormented genius, which suggests this interpretation of the letter). In the letter, Brown writes nostalgically about ‘notre bonne, ta chere mamma’ (‘our maid, your dear mama’). Brown begins the letter by asking ‘Pourquoi ne m’écrit ta pas[?]’ (‘Why haven’t you written to me?’). If the letter’s recipient was indeed the daughter of Brown’s former maid, it is perhaps not surprising that she was in no hurry to write friendly letters to the woman who had enslaved her mother and used the profits to move away, abandoning any obligations she might have felt towards her maid’s family. Is it possible that the staunchly pro-abolition Édouard felt regret or even guilt that his success was greatly facilitated by his family’s involvement with slavery?

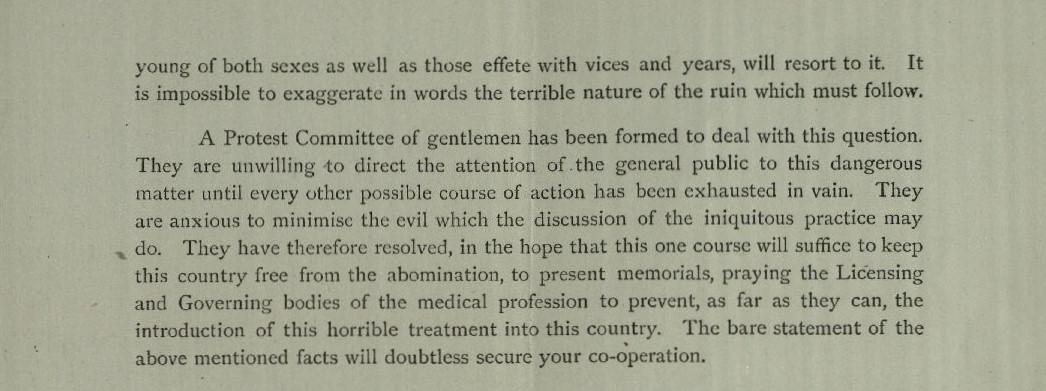

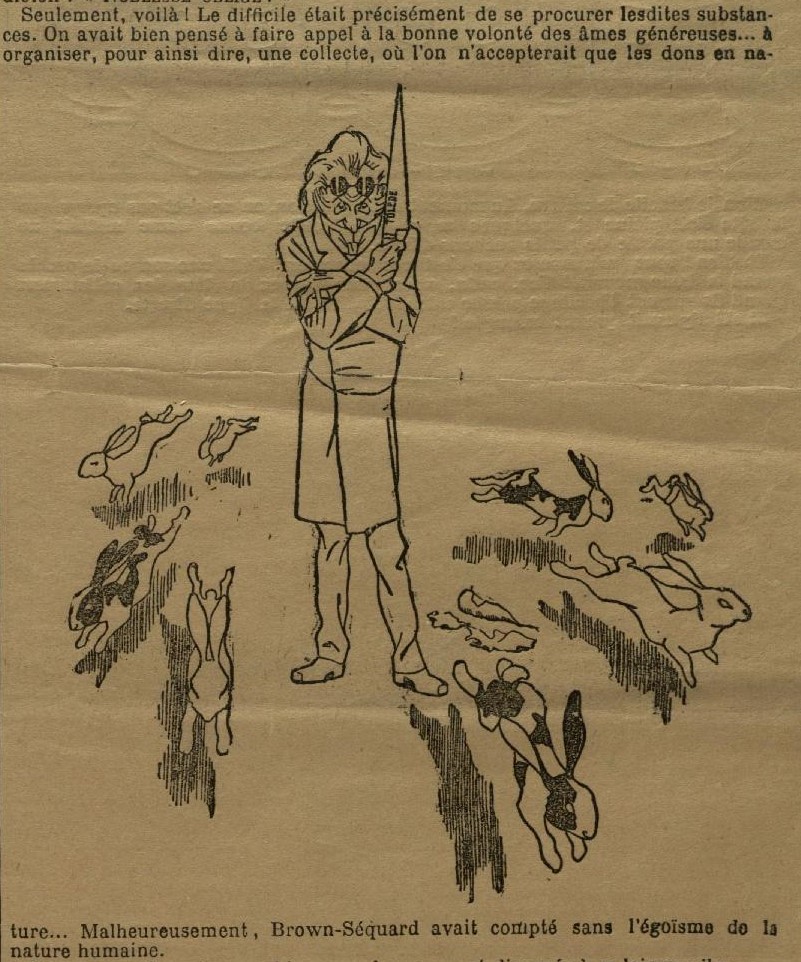

After the revolution, Édouard left Paris. He had inherited his father’s seafaring spirit, and never settled in one country, or one continent, for long. He travelled first to Philadelphia, his father’s birthplace, and then to New York, which is where he met Ellen. After leaving Virginia and returning to Europe, he continued to conduct medical research and publish his findings; Brown-Séquard syndrome is a neurological condition named after him. In later years, his animal experimentation again caused controversy when he began injecting himself with the testicular fluid of guinea pigs and other creatures. He claimed the process had the power to rejuvenate the male body, restoring virility and prolonging life. However, the RCP archives contain several leaflets produced by outraged religious organisations, accusing Édouard of encouraging masturbation. One leaflet reads, ‘unless an immediate and resolute stand be made by all the moral forces of the country against it, the abominable and unspeakably disastrous practice of self-abuse will receive a medical sanction, and the young of both sexes as well as those effete with vices and years, will resort to it. It is impossible to exaggerate in words the terrible nature of the ruin which must follow’ (MS980/68). Édouard had written about the benefits of masturbation for older men, but his testicular fluid serum was the main thrust of his efforts in rejuvenation. Despite the uproar caused at the time, his work has since been recognised as fundamental to the establishment of the science of endocrinology, and his experiments as paving the way for hormone replacement therapy.

Édouard returned to Mauritius throughout his life, including to assist with a cholera epidemic in 1849. But it was his first journey back after emigrating that was to prove the most fateful. In 1842, while at university in Paris, Charlotte Brown died. Édouard was devastated; his mother had devoted herself to him his whole life and he felt lost without her. Unsure if he even wanted to continue his career as a scientist, he quit his studies and booked passage on a ship home. As it entered the Indian Ocean, a ferocious cyclone struck the ship. The other passengers fled to their bunks, but Édouard refused to cower before the phenomenon that had killed his father. His observational impulse took over, and gathering up his notebook, he strode on deck and began making notes on the weather conditions. The ship was ravaged by the storm, but the crew steered her through, and she eventually docked safely in Mauritius. Édouard disembarked with one of the earliest detailed descriptions of the structure of a cyclone, including the then little-studied calm eye of the storm. He had used his intellect to tame the beast that had taken his father from him before his birth, and he had reaffirmed his devotion to science. He might never be able to banish the other ghost that haunted him, the knowledge that he owed his success in part to slavery money, but he was determined to honour the faith his mother had in him by using his medical knowledge for good. He adopted her maiden name, Séquard, to honour her memory. Before leaving to return to university, he delivered a talk based on his storm research to the Royal Society of Arts and Sciences of Mauritius; its title, ‘La Trombe’ – ‘The Whirlwind.’

Felix Lancashire, assistant archivist

Sources used in writing this post:

- Bouton, L. (ed.), Procès-verbaux de la Société d’Histoire Naturelle de l’isle Maurice du 6 Octobre 1842 au 28 Aout 1845, Port Louis,1846:30-31

- Brown, G.H. (1955), ‘Charles Édouard Brown-Séquard’ in Brown, G.H. (ed.) Lives of the fellows of the Royal College of Physicians of London 1826-1925 (vol.4)

- Celestin, Louis-Cyril, Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard – the biography of a tormented genius, London: Springer, 2013

- Watson, Joseph C. and Ho, Stephen V., ‘Charles Edouard Brown-Séquard’s departure from the Medical College of Virginia: incompatible science or incompatible social views in pre-Civil War Southern United States’, World Neurosurgery 75, 2011, 5/6:750-753

- Williams, Harley, The healing touch, Springfield, Ill. : Charles C Thomas, publisher, 1951:221-270