A Story of Power Emerges from the Pages

During summer 2022, the RCP archives team were delighted to welcome Traci Picard, Public Humanities masters student at Brown University, Rhode Island. Traci has begun creating a super-index of our 40-or-so handwritten medical recipe books, which will enable researchers to search across the whole collection for particular ailments, remedies, and ingredients. The super-index will go online in 2023, and we are currently uploading the books themselves to the Internet Archive.

The early modern receipt books contain many stories. People and places, illness and recovery, bodies and belief. How is a recipe a story? The recipes are not just data points but combinations of ideas about our health, about raw materials and what to do with them which have origins in the distant past, ideas which compound with each passing century like snowballs picking up a little bit of this and that, mixing ancient techniques with migratory ingredients.

The super-index project, an exploration of each handwritten recipe book and its emerging ingredient dataset, will help the reader to ask questions of individual books, and also across the books. Understanding history is not just knowing random points of information but making connections between these points. Someone can search how many times elecampane, quinces or pigeon dung appear in this collection, and that is useful. But they can also use it to explore power. One can trace who was more likely to record complex recipes compared to simple ones, consider the origins of certain ingredients and observe how individuals changed “classic” and often-repeated recipes such as Galen’s unguent to suit their own economic needs. Why might one writer have access to more ingredients than another, to fancier ingredients or a bigger pantry to store jar upon jar of preserves and syrups and potions? And why are there hundreds of mentions of refined sugar in these books, but very few of treacle?

The index tool leads a user from one ingredient or condition to another through curiosity and can help to point researchers towards areas of further study. The dataset also leaves the researcher with impossible questions; unknowable bits to think about. Perhaps they are philosophical or perhaps they are practical, but as with all history, there is still a limit to our knowing.

The data can also help us follow ingredients around the world, tracing the movements of people by the raw materials they bought and sold. How did each of these materials get to London? Sassafras, ivory, sugar and mastic are all examples of the hundreds of raw materials with stories of their own; stories of colonisation, movement, empire, violence and capital. Their stories include the foragers, producers and processors whose hands are in the making but whose names may not appear in the history books. Might they include enslaved people, Indigenous people, and others working to survive difficult and oppressive circumstances? The books don’t name them, but their contributions are invaluable, and worthy of our study and acknowledgement.

The realities of racialized slavery are inherently tangled up with these books, an outsourcing of labour which is easy to overlook in a haze of nostalgia about a lovely Lady of the house pounding her herbs in a mortar and pestle, drifting about the fields collecting meadowsweet and snails, and kindly bathing the toes of every noble gout-stricken gentleman caller. And perhaps she did. But her hand, which scooped refined sugar into a British pot, is inextricably connected to the hand which cut the cane on a Jamaican plantation. It is tempting to look away from the messy realities, the power dynamics, the social history of each ingredient, the uncomfortable gaps in access which persist even today. Each syrup was simmered at the expense of something else, someone else. The sugar refineries ate up fuel, deforested islands, and pushed England ever more deeply into the Industrial Revolution.

Whose voice is centred in this collection, and whose is left out? I touched previously on the often untold stories of makers which are inherent in each ingredient, but there is another important question to explore through these books: who gets the credit for making them? Researchers can use recipe books as a tool for exploring power and class in so many ways. It is not only the misery of the oppressed that these books transmit, but their skill too. Workers growing, collecting and processing ingredients may have felt pride in their abilities and knowledge. Perhaps they had relationships with the plants and animals, or found themselves in a lineage of foraging, or believed in the contributions they were making.

These questions are opportunities. Stories of the global power dynamics linked to early modern medicine are not a burden, just a reality which helps us give context to the books. The ability to read them “against the grain” adds a richness to the history of medicine, which is in fact everyone’s history. Many illnesses and conditions have social connotations, and many remedies are symbolic of wealth, access, and abundance…or of making do. The skill of literacy, the leisure time to write, the relationships with medical doctors and minor royalty, the ownership of books, the storage space for all of these medicines and the time and space needed to pound a sheep’s head into powder are all examples of why the historic record is uneven.

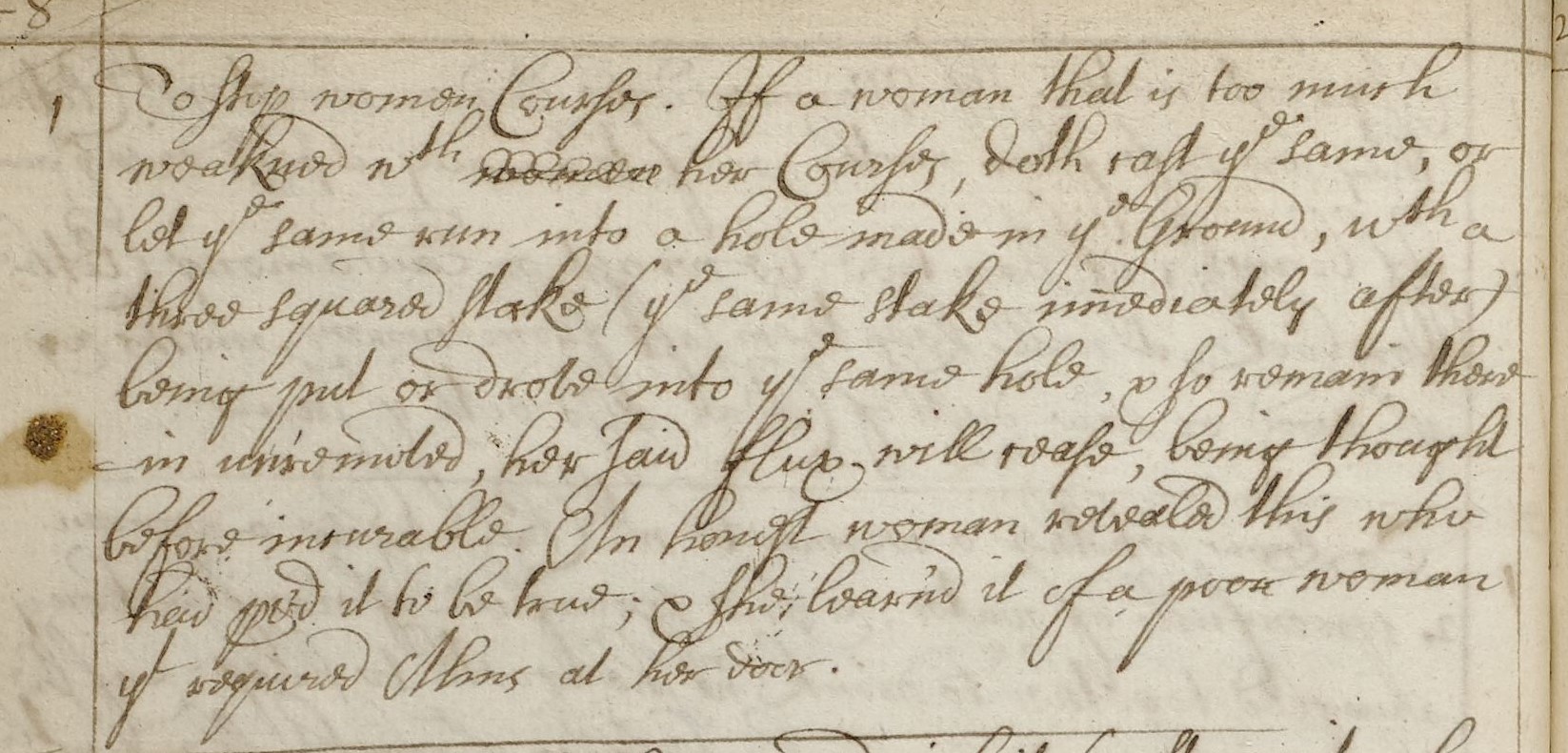

That said, the voices of many people are in there if one looks. There are a small number of receipts attributed to household servants, often identified by the possessive: Lady Oxford’s cook, Lady Diana’s woman Mrs. France, and Lady Vere’s woman Mrs. Watson. One recipe is attributed to a woman asking for alms, another to the honorific-free Bety Bolton. The layers of social hierarchy are made clear, and although many individual contributors may remain nameless, researchers can choose to see them; to acknowledge and give credit to the workers, producers and knowledge-keepers for making many contributions to healthcare throughout history.

Traci Picard

Archives Volunteer