Letters in the RCP archives written by the pioneering feminist and physician, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836–1917) demonstrate her determination to achieve success in the then almost exclusively male field of medicine. In 1865, Garrett Anderson had been the first Englishwoman to qualify in medicine in England and in 1873 the first female member of the British Medical Association (the only one for 19 years).

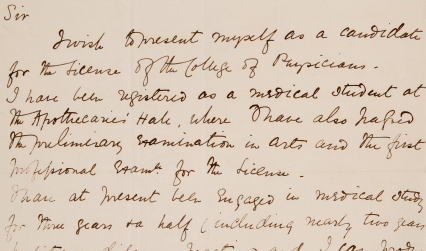

In 1864, Garrett Anderson had applied to the RCP to take the exam for the LRCP medical diploma:

I have been registered as a medical student at the Apothecaries Hall, where I have also passed the preliminary examination in Arts and the first professional examn for the license … I can produce all necessary certificates of study from recognized teachers in acknowledged schools of medicine. I trust you will pardon me if I mention, in addition to these details, my special reasons as a woman for desiring to become a candidate for the license of the College. In endeavouring to open the profession of medicine to women I have wished above all things not to assist in lowering the standard either of preliminary or professional education.

The RCP refused to admit her to the examinations for the licence but she did qualify for the LSA, the Society of Apothecaries’ licence to practice. After she passed in 1865, the Society immediately changed its charter to stop any other woman following Garrett Anderson’s example.

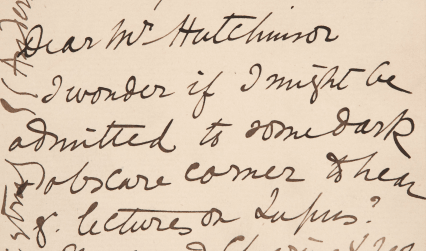

Garrett Anderson married James Anderson in 1871, changing her name from ‘Garrett’ to ‘Garrett Anderson’. She continued to practice medicine and to be an advocate for education and careers for women. Despite her medical qualifications, she still faced continuation discrimination in many places. In 1887, she asked permission to unobtrusively attend a lecture at one of the medical societies associated with the RCP. She wrote:

Dear Mr Hutchinson, I wonder if I might be admitted to some dark obscure corner to hear y[ou]r lectures on Lupus? The good Charing X people are admitting women to their post graduate course so it w[oul]d not be quite novel if the Harveian Soc were disposed to be gracious. Do not trouble to answer unless you can say ‘yes’.

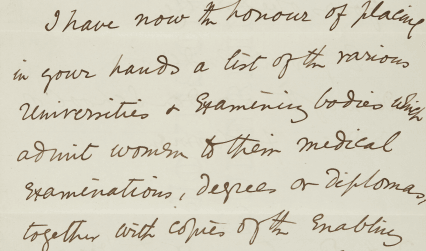

In 1895, Garrett Anderson – by then dean of the London School of Medicine for Women – contacted the RCP again, pointing out that five universities and six professional organisations in Great Britain and Ireland now admitted women:

I have now the honour of placing in your hands a list of the various universities and examining bodies which admit women to their medical examinations, degrees or diplomas.

But it was to be another 14 years before the RCP opened its doors to women. In January 1909, a bye-law allowing women to take RCP exams was passed. In 1925, women were also allowed to be elected as fellows (voting members): the first to achieve this status, in 1934, was Helen Mackay (1891–1965). From then on the progress of women through the ranks of the membership, and the profession, accelerated, although Dame Margaret Turner-Warwick (born 1924), the RCP’s first female president, was not elected until 1989.

Pamela Forde, archive manager

Garrett Anderson’s 1887 letter was featured as part of the Royal Mail’s Letters of our Lives gallery.