Although Sir Samuel Garth’s satire The Dispensary (1699), on the building of a medicines dispensary for the poor at Royal College of Physicians, has now been largely forgotten, at the time of its publication the poem was an instant success, making the writer the talk of the London coffee houses and the fashionable literary scene.

As Garth (1661–1719) recounts in his preface to The Dispensary, he was inspired to write his poem after learning of a fracas ‘betwixt a Member of the College with his Retinue, and some of the Servants that attended there, to dispence the Medicines’. The member was presumably one of the ‘anti-dispensarian’ physicians at the RCP, who had allied themselves with the apothecaries in their long campaign against the dispensary.

The physicians and the apothecaries had had an uneasy relationship throughout the 17th century. The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London was incorporated by royal charter in 1617. At first, the two professions were distinct; the apothecaries prepared and sold drugs and were subservient to the physicians, who diagnosed and treated patients. But over the course of the century, particularly as London’s population grew, the apothecaries began to see patients and prescribe as well as prepare medicines. Over decades, the physicians and apothecaries battled to assert their professional predominance, with tract and counter tract being published and regular appeals made to Parliament.

In 1687, amidst this controversy, the Royal College of Physicians announced that its members would give free treatment to paupers and proposed the building of a public dispensary based at the College, where the poor could receive free medicines. While the apothecaries were angered by what they saw as a direct threat to their livelihood, there was also fierce opposition from some physicians. Despite these ongoing disagreements, in 1696, the RCP committee on medicines again proposed the establishment of the dispensary, and by the end of the year 52 college members had subscribed £10 each to support the project.

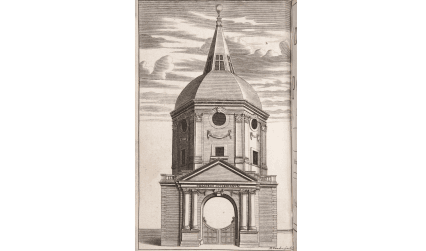

Garth, a member of the medicines committee and a subscriber to the dispensary, referred to the controversy in his Harveian Oration of 1697. The college’s ‘mutual love and affection’ had been disrupted, he argued; there was a need for ‘unitie and concord’. The rancour continued, but in spring 1698 a dispensary was opened at the college’s Warwick Lane building, with two more later opening in St Martin’s Lane and Gracechurch Street.

A year later, in 1699, Garth published his satirical poem in six cantos, mocking some of the key protagonists in the dispute. The poem begins with a description of the newly constructed college building on Warwick Lane, with its striking ‘Dome, Majestick to the Sight…’ But within its walls the fellows and members are disunited and the God Sloth has taken up residence. He is awakened from his slumbers by the sound of the construction of the dispensary, so sends his servant Phantom to summon the Goddess Envy. Phantom finds Envy, who assumes the shape of Colon, an apothecary. Colon in turn visits a fellow apothecary, Horoscope, in his shop, where ‘Mummies lay most reverendly stale, / And there, the Tortois hung her Coat o’Mail; / Not far from some huge Shark’s devouring Head.’

When Horoscope hears of the building of the dispensary, he faints at the prospect of losing his income and spends a restless night working out how to respond. He sends his servant to summon the apothecaries. At the Apothecaries’ Hall, Ascarides suggests they ally themselves with the physicians who are against the dispensary. At Covent Garden, Mirmillo has brought together a group of anti-dispensarian physicians. The Bard recites some doggerel in an attempt to rouse Disease to help. Then Mirmillo has a sleepless night worrying about the coming confrontation, but Goddess Discord assumes the form of Querpo, another anti-dispensarian physician, and gives a rousing call to arms.

At dawn, the apothecaries and their physician allies gather for an attack on Warwick Lane. In the battle, all manner of medical paraphernalia is used, including syringes, gally-pots and broken phials. Querpo is just about to slay Stentor, the leader of the physicians, when Apollo steps in in the guise of Fee, at which Querpo instinctively snatches.

In the final canto, Hygeia, the Goddess of Health, appears and asks one of the physicians, Machaon, to send Carus to accompany her to the Elysian Fields to consult with the shade (ghost) of William Harvey. In the underworld, Harvey is despondent about the state of the college: ‘How sik’ning Physick hangs her pensive Head. / And what was once a Science, now’s a Trade.’ Only by attending to science and the nation’s health will the college’s former prestige be restored.

The poem was an outstanding success. In 1699 alone three editions were published, eight were produced during Garth’s lifetime, and the text was reprinted regularly throughout the 18th century. The contemporary popularity of the poem can be partly attributed to the public’s interest in identifying the key players. Mirmillo, the anti-dispensarian physician, seems to have been William Gibbons; the Bard is Sir Richard Blackmore; Stentor, the leader of the physicians in the battle, is thought to be Charles Goodall; while Machaon, another of the physicians, is Sir Thomas Millington. Samuel Johnston, in his life of Garth, also suggested the poem appealed because of its clear moral stance. After all, Garth was ‘on the side of charity against the intrigues of interest, and of regular learning against licentious usurpation of medical authority’.

Blackmore (‘The Bard’ in the poem and a leading anti-dispensarian) published A Satyr against Wit, a leaden riposte, in November 1699, but Garth’s The Dispensary effectively silenced most of the opposition to the project. The dispensary at the Royal College of Physicians remained open until 1724 (though the two branches may have survived for several years after), but the rivalry and professional disagreements with the apothecaries rumbled on.

Apart from his considerable political influence, Garth can also be credited with being one of the first to use the ‘mock-heroic’ form in English, a form where the style of heroic, classical literature is used to satirise an unheroic subject. Even Garth’s literary contemporaries recognised that he had borrowed heavily from the mock-heroic poem Le Lutrin (The Lectern) (1674), by the French poet and literary critic Nicholas Boileau, who similarly used an actual event, a dispute between clerics, as the basis for his satire. Garth successfully ‘translated’ the idea into the medico-political context of the Royal College of Physicians, and importantly may have inspired his younger friend (and more influential poet) Alexander Pope to use the form in his best-known poem, The Rape of the Lock (1712).

Apart from some translations, Garth wrote very little after finishing The Dispensary. He continued his career as a successful physician and played an increasing role in contemporary politics. He was a member of the Kit-Kat Club of leading Whig public figures and, when the Hanoverian, Whig-friendly George I ascended the throne, he gained a knighthood and was made a physician-in-ordinary to the king.

Sarah Gillam, assistant editor, Munk's Roll

The following sources were used when writing this post:

- Booth, C C. Sir Samuel Garth, FRS: The Dispensary poet. Notes Rec R Soc Lond. 1986 May;40(2):125-45.

- Brander, B. Samuel Garth’s The Dispensary. Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, Bernard Becker Medical Library. 14 April 2016. https://becker.wustl.edu/about/news/national-poetry-month-samuel-garths-dispensary – accessed 31 August 2017.

- Clark, G. A history of the Royal College of Physicians of London Volume Two. London: Oxford University Press, 1966.

- Ellis, F H (ed). Poems on affairs of state: Augustan satirical verse, 1660-1714. Volume VI: 1697-1704. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1970.

- Jones, A H. Literature and medicine: physician-poets. The Lancet 349.9047 Jan 25, 1997: 275-8.

- Martensen, R L. Garth, Sir Samuel (1660/61-1719). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2005 www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/10414 – accessed 17 August 2017.

- Munk, W. The Roll of the Royal College of Physicians of London. Vol 1, 1518 to 1700. London: Royal College of Physicians, 1878.

- University of Sheffield. The University Library. Poetry in medicine. www.sheffield.ac.uk/library/special/poetryinmedicine – accessed 31 August 2017.