This post discusses historical attitudes to sex, sexuality and gender, and quotes language and attitudes considered offensive today.

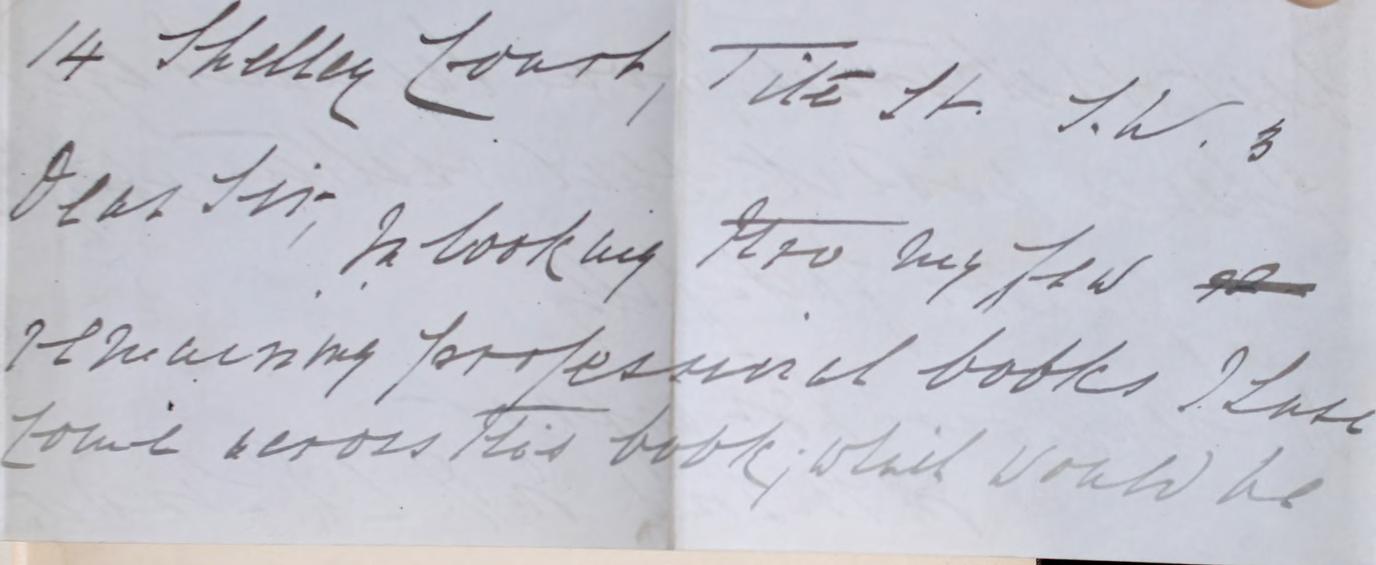

A tiny handwritten note only a few centimetres across has been carefully stuck into the front of one of the books in the RCP library. The handwriting is rather sprawling and unclear, but you can just about make out what it says.

14 Shelley Court, Tite St, SW3

Dear Sir,

In looking thro[ugh] my few remaining professional books I have come across this book; which would be best sheltered from laymans’ eyes. Please give it such shelter; & oblige.

Yours faithfully,

H. Seymour Branfoot

MB. Lond. M.R.C.P. Lond etc

The RCP library recorded Branfoot’s donation of a single book on 20 March 1919, and we’ve had it on our shelves ever since.

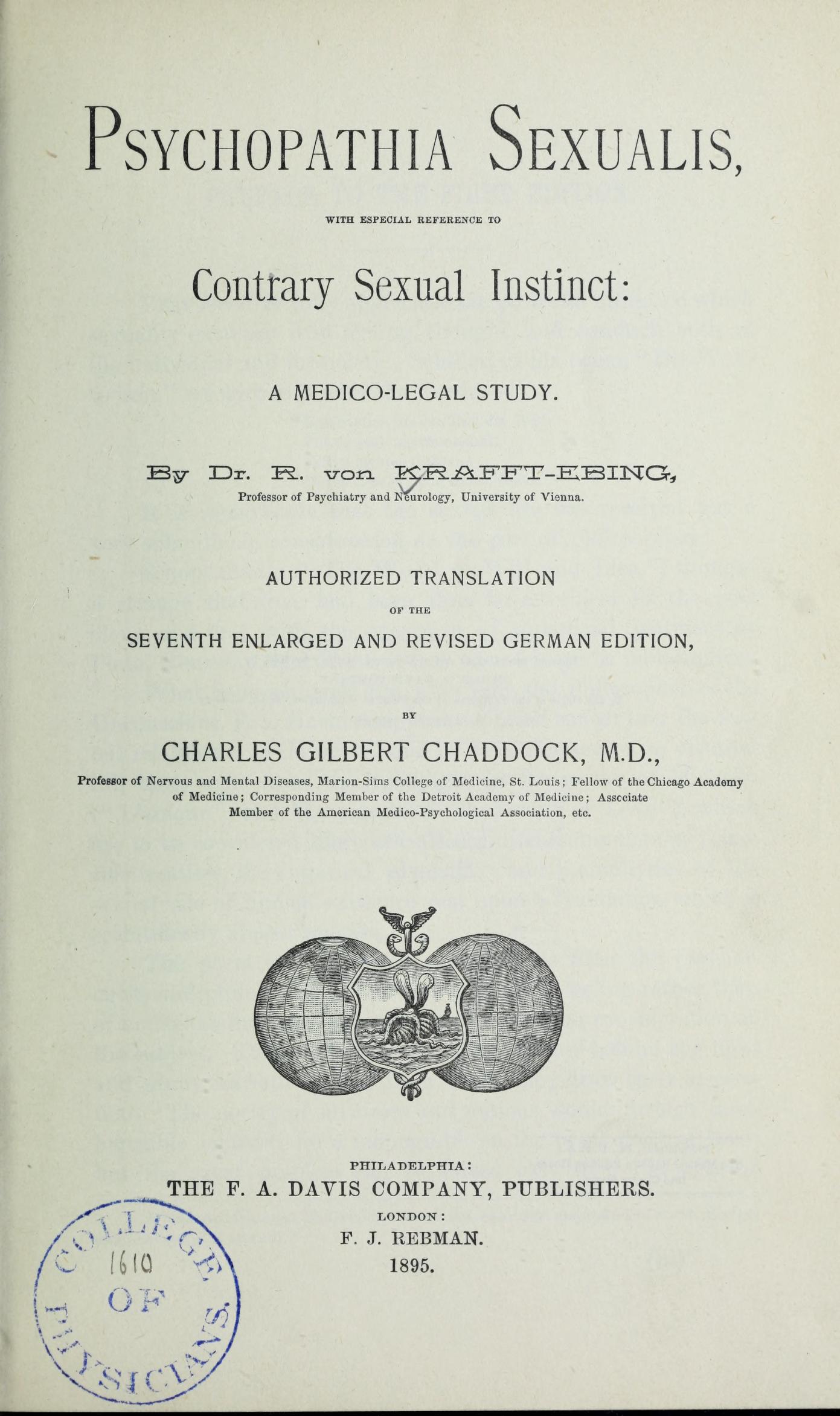

What made this particular book in such perceived need of ‘shelter’ from lay people? The title will give you a strong hint: Psychopathia sexualis with especial reference to contrary sexual instinct: a medico-legal study. Originally published in German in 1886, this book by psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing (1840–1902) is about sexual psychology, specifically about sexual practices and interests deemed to be pathological or diseased. The original title was Psychopathia sexualis: eine klinisch-forensische Studie in 1886.

In his preface to the first edition of the book, Krafft-Ebing laid out his purpose in writing it. He wished to provide a ‘scientific’ study of ‘pathological manifestations of the sexual life’, to assist in the fields of medicine and law. He was concerned that ‘unjust sentences’ were meted out to people accused of sexual crimes. He wished to demonstrate to the lawyers, judges, and medical expert witnesses involved in legal cases that these perpetrators were not morally deficient, but rather subject to medical and psychological problems needing treatment rather than punishment.

It is the sad province of Medicine, and especially of Psychiatry, to constantly regard the reverse side of life,–human weakness and misery.

Perhaps in this difficult calling some consolation may be gained [...] if it be possible to refer to [i.e. attribute to] morbid conditions much that offends ethical and aesthetic feeling. Thus Medicine undertakes to save the honor of mankind before the Court of Morality, and individuals from judges and their fellow-men.

The book ranges widely, covering topics including sex and religion, fetishes, physical and mental causes of sexual dysfunction, sadism, sexual violence, and the legal aspects of sexual behaviour. Some topics such as those termed ‘contrary sexual instinct’, ‘psychical hermaphroditism’, ‘effemination and viraginity’ can be mapped to what we would today consider to be a range of LGBT+ identities. Krafft-Ebing uses case studies based on his work in psychiatric hospitals and asylums, and from his private practice as a psychiatrist. Extended first-person accounts are reproduced throughout the book.

Krafft-Ebing was conscious of a possible negative impact of this book being read outside specialist medical and legal circles.

The following pages are addressed to earnest investigators in the domain of natural science and jurisprudence. In order that unqualified persons should not become readers, the author saw himself compelled to choose a title understood only by the learned, and also, where possible, to express himself in terminis technicis [technical language]. It seemed necessary also to give certain particularly revolting portions in Latin rather than in German.

This use of Latin is preserved in the English translation by American neurologist Charles Gilbert Chaddock (1861–1936), first published in 1892. The British Medical Journal review of the book questioned whether it should have been translated at all, considering that specialists would have been able to read the original German text. Indeed, it even suggested that it would have been better written entirely in Latin and therefore kept ‘veiled in the decent obscurity of a dead language’, because ‘There are many morally disgusting subjects which have to be studied by the doctor and by the jurist, but the less such subjects are brought before the public the better.’ In fact, the translation is a testament to English as a living, continually changing language, being one of the earliest printed uses of the word ‘homosexual’ in the language.

Chaddock’s preface to the English edition notes the controversy about the book’s publication, citing debate about whether a book that had run to seven editions in German could possibly only have been bought by specialists. Surely, reasoned some, for demand to be so high it must also have been bought by the general public keen to use it as pornography? There was likely also concern that audiences reading about some of the disapproved-of practices described in the book might be tempted to try them themselves, and that it might unlock any latent or repressed desires. The implication of this is that medical and legal professionals were a separate class of person by dint of their training and education, and were well above behaviour deemed so undesirable.

Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection

Today, the language in Psychopathia sexualis can be upsetting to read. The descriptions of non-procreative sexual activity and of same-sex desires as pathological, diseased and perverse are judgemental and unsympathetic. The descriptions of people who today might describe themselves as having a range of sexual and gender identities (such as gay, lesbian, bisexual, asexual, intersex, trans and others) seem crude, reductive and insulting. Krafft-Ebing’s tone towards his objects of study often seems patronising and pitying, rather than sympathetic.

Homo-Sexual Individuals, or Urnings.–In distinction from the preceding group of psycho-sexual hermaphrodites, there are here, ab origine [from the beginning], sexual desires and inclinations for persons of the same sex exclusively; but in contrast with the following group, the anomaly is limited to the vita sexualis [sexual life], and does not more deeply and seriously affect the character and mental personality.

The vita sexualis of these urnings, mutatis mutandis [with the necessary alterations], is entirely like that in normal hetero-sexual love; but, since it is the exact opposite of the natural feeling, it becomes a caricature, and this the more, since these individuals, at the same time, as a rule are subject to hyperaesthesia sexualis [excessive sexual sensitivity], and, therefore, their love for their own sex is emotional and passionate. (page 255)

However, even this disparaging and – often – obviously disgusted representation of his subjects of study brought comfort to some people at the time. In Stepchildren of Nature (2000), Harry Oosterhuis records that Krafft-Ebing received letters of thanks from lay readers reassured to know that they were not alone, and by his description of them as medically, rather than morally, flawed. Many LGBT+ people today will recognise the jolt of familiarity and reassurance that comes from seeing yourself represented, even if it’s in unsympathetic and derogatory terms, when your identity seems to go otherwise undocumented in society and the media.

About the donor

Henry Seymour Branfoot (1851–1919) studied medicine at Guy’s Hospital, London, and worked there as well as in Oxford and Manchester before becoming the consulting physician to the Sussex County Hospital in Brighton. He retired from medical practice around the year 1911, aged 60 or so. This is the last year in which he has an entry in the Medical directory, and The Times of 10 May 1911 recorded that he had resigned his commission as Lieutenant-Colonel of the Royal Army Medical Corps 2nd Eastern General Hospital, Brighton.

His address on the donation letter of 1919 – 14 Shelley Court, Tite St, SW3 – places him in an apartment close to the river in the London Borough of Chelsea, a suitable spot to retire to. We don’t know if Branfoot had a particular interest in psychopathology or sexology. Maybe he bought the book because it had caused quite a sensation, maybe it was useful to his medical work, or maybe he had a personal interest.

Branfoot’s scrawled donation note reveals a lot about societal attitudes in the early 20th century; a desire to hide that which is deemed unsavoury or undesirable from ‘innocent’ eyes which hasn’t necessarily entirely disappeared in the UK today, even though legal and medical attitudes to LGBT+ people have changed substantially. In recent years, for example, arguments about the appropriate ways to educate school children about LGBT+ identities have continued to rage, but there’s no denying that information about sexuality and gender is far more accessible than it was in Branfoot’s time.

Katie Birkwood, rare books and special collections librarian

Resources used in writing this post:

- Anonymous. Review of the English translation of Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia sexualis with special reference to contrary sexual instinct: A medico-legal study (1892). BMJ 1893;1: 1325.

- Cook M, Pick D and Ffytche M. Deviance, disorder and the self. London: Birkbeck College, 2003–10. [Accessed 26 January 2021].

- Oosterhuis H. Stepchildren of nature: Krafft-Ebing, psychiatry and the making of sexual identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000. Cited in Cheadle T, Sexology and the ‘Invention’ of Homosexuality. FutureLearn, 2020. [Accessed 26 January 2021].

- Schmid A. Psychopathia Sexualis: A Historic Peepshow of Sexual Pathology and Criminology Appealing to Scholars, Artists and Common People Alike. Indiana University School of Medicine, Medical Library blog, 8 May 2020. [Accessed 26 January 2021].

- Wellcome Collection. Sexology collections. Accessed 26 January 2021].

Taking place in February every year, LGBT+ history month celebrates the lives and achievements of the LGBT+ community. It also aims to promote tolerance and raise awareness of the prejudices faced by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and other people with gender identities and sexual orientations that are not specifically covered by the other five initials.