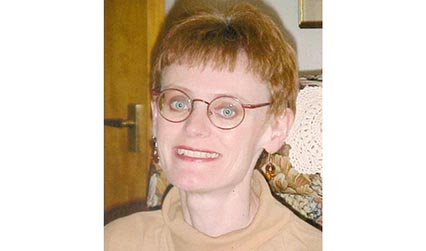

Sarah Walters, who died in 2018 at the age of 59, was the first person with cystic fibrosis (CF) to qualify as a doctor, setting a precedent for other people with disabilities to train in medicine. She also made a contribution to research into CF: as a senior lecturer in public health medicine at Birmingham University she demonstrated the importance of adults with CF having access to specialist clinics – work which has influenced national policy.

People with CF experience a build-up of thick, sticky mucus in the lungs, digestive systems and other organs, causing a wide range of complex, life-threatening symptoms. Although, as a genetic condition, CF has occurred for thousands of years, it was only identified and named in the 1930s. In 1936 Guido Fanconi wrote a paper in German outlining the traits of CF; in the United States credit is given to the pathologist Dorothy Andersen (1938) or Kenneth Blackfan and Charles May (1938) for first describing the condition.

For generations, the outlook for children born with cystic fibrosis was bleak. When Sarah was born, in 1958, very few children with CF lived beyond early childhood. A study by D J Mantle and Archie Norman (1966), looked at CF survival rates from the 1940s to 1964. They showed 80 per cent of those affected had died by the age of five, 90 per cent had died by ten and there were no adults. Sarah was finally diagnosed at the age of 11 and shortly afterwards was given just two years to live. Luckily, she was treated with new, high-dose antibiotics during her childhood, which gave her a chance of life.

Sarah had already decided – at the age of three – to become a doctor. She excelled at school, gained good A levels and applied to several medical schools, but none offered her a place. Undeterred, she decided to do a degree in microbiology at Surrey University. In an article she later wrote for the BMJ, she noted: ‘Contrary to expectations, I flourished away from home and obtained not only a first but the confidence to argue and persuade my way into medical school.’

She reapplied and was finally accepted into St George’s in London – an unprecedented move for the medical school. She had no money to pay for the course, but the chairman of the Cystic Fibrosis Trust sponsored her training, she won a scholarship and an exhibition, and earned money during the weekends and vacations as a medical secretary, electrocardiograph technician and nursing auxiliary. She qualified in 1985 with a distinction.

After junior posts, she was a registrar in respiratory medicine at East Birmingham Hospital, but later switched to public health medicine; she was a senior registrar for the West Midlands Regional Health Authority and in 1992 was appointed as a lecturer and then senior lecturer in public health and epidemiology at the University of Birmingham. In 1994, she set up and ran the masters in public health, pioneering a modular and part distance learning approach. She led the programme for more than ten years.

In her BMJ article, she stressed that, while her experiences as a trainee were much the same as any other junior doctor, she had also ‘…been ill myself, I have been an inpatient, I have waited hours in outpatients, I have had many diagnostic tests, and I have had many peripheral venous and central lines inserted in me. I have experienced the fear of not getting better...’ In short, she knew what it was like to be a patient, and she believed her experiences had a positive impact on her work as a doctor. She felt she knew what the patient needed to hear, and, in turn, she found ‘Patients are often fascinated to find that you have an illness yourself. You become one of “us” not just one of “them”’.

Sarah also researched into the experience of adults with cystic fibrosis. Her 1993 paper showed that a high proportion of adults with CF in the UK were living full and productive lives, a finding that contradicted several earlier findings. A year later, she co-wrote a report on the medical care received by adults with CF. The findings were stark: adults attending specialist clinics received more detailed care, had better symptom control, and were more satisfied with the service than those attending general chest clinics. Leading CF organisations now recommend all adults with cystic fibrosis should, where possible, receive medical care at specialist clinics. Sarah was also part of a team in Birmingham investigating the impact of air pollution on health.

Eventually, her health deteriorated and in 2006, at the age of 48, she took early retirement. But she still wanted to contribute. With her husband, Stephen Briggs, she bought Alvecote Wood, a neglected ancient woodland near their home in Tamworth. They both learnt woodland management and practical skills, including driving a tractor and operating a chainsaw, and in 2014 they received an award from the Royal Forestry Society.

Sarah died in April 2018 after catching flu. As the first person with cystic fibrosis to train as a doctor, she led the way for other people with disabilities to go to medical school. As she noted in an interview for the St George’s website, ‘There are now quite a few other doctors with cystic fibrosis, and with other disabilities, and I think that St George’s were enlightened to try and take people with disabilities on and prove they could become successful doctors.’ She undoubtedly proved they could and more than lived up to her wish to be remembered as ‘Somebody who made a difference, not only to the lives of people, but to the planet too.’

Sarah Gillam, editor of Munk’s Roll

The exhibition Catch your breath is open free of charge 9am–5pm, Monday–Friday until 20 September 2019.

References:

- Adab P, Marshall T. Sarah Walters. BMJ. 2018;361:1818 www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k1818 – accessed 20 May 2019.

- Alvecote Wood Ancient Woodland for Wildlife www.alvecotewood.co.uk – accessed 20 May 2019.

- Andersen D H. Cystic fibrosis of the pancreas and its relation to celiac disease. A clinical and pathologic study. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1938;56:344-99.

- Blackfan K D, May CD. Inspissation of secretion and dilation of ducts and acini. Atrophy and fibrosis of the pancreas in infants. Paediatrics 1938;13:627-34.

- Christie DA, Tansey E M (eds). Wellcome witnesses to twentieth century medicine volume 20: cystic fibrosis. London, Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 2004.

- Fanconi G, Uehlinger E, Knaver C. Das Coeliacsyndrom bei Angeborener zysticher pankreas fibromatose und bronchiektasen. Wien Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1936;86: 753–56.

- Mantle D J, Norman A P. Life-table for cystic fibrosis. BMJ. 1966;2:1238-41.

- St George’s University of London Five minutes with… 27 August 2014 www.sgul.ac.uk/news/news-archive/five-minutes-with-sarah-walters-obe – accessed 20 May 2019.

- The history of cystic fibrosis. www.cfmedicine.com Growing older www.cfmedicine.com/history/topics/olderCF.htm – accessed 20 May 2019.

- University of Birmingham Public Health at Birmingham. Dr Sarah Walters 12 April 2018 https://blog.bham.ac.uk/publichealth/2018/04/12/dr-sarah-walters/ – accessed 20 May 2019.

- Walters S. A doctor despite a disability. BMJ. 1988;297:1665-6.

- Walters S, Britton J, Hodson M E. Demographic and social characteristics of adults with cystic fibrosis in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 1993;306:549-552.

- Walters S, Britton J, Hodson M E. Hospital care for adults with cystic fibrosis: an overview and comparison between special cystic fibrosis clinics and general clinics using a patient questionnaire. Thorax. 1994;49:300-306.