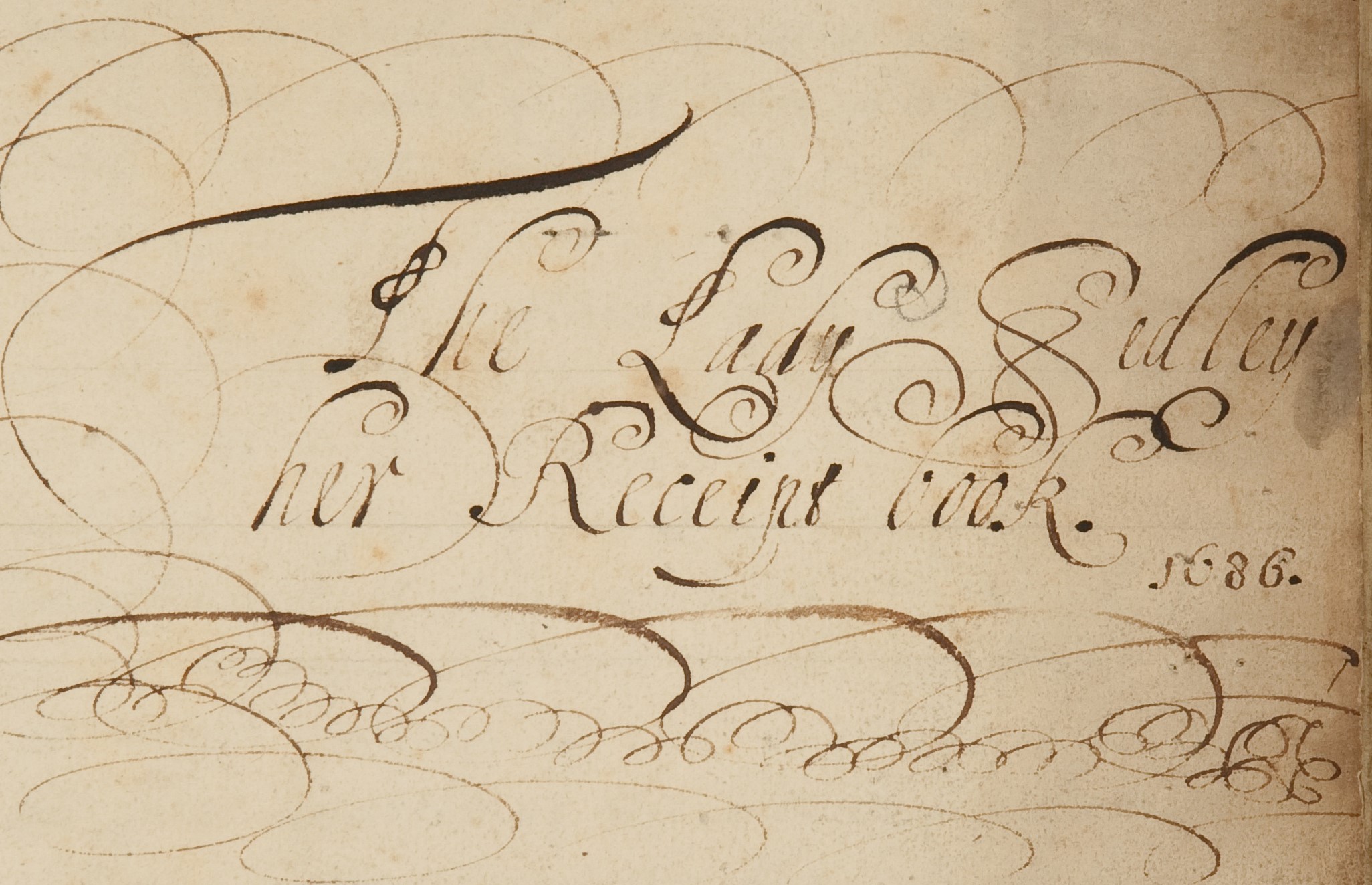

The archives at the Royal College of Physicians contain a substantial collection of handwritten recipe books, manuals containing medical treatments and ingredients. These are fascinating and frustrating volumes. One of the most mysterious is manuscript 534. It has an inscription on the first page which states “Lady Sedley her receipt book 1686”.

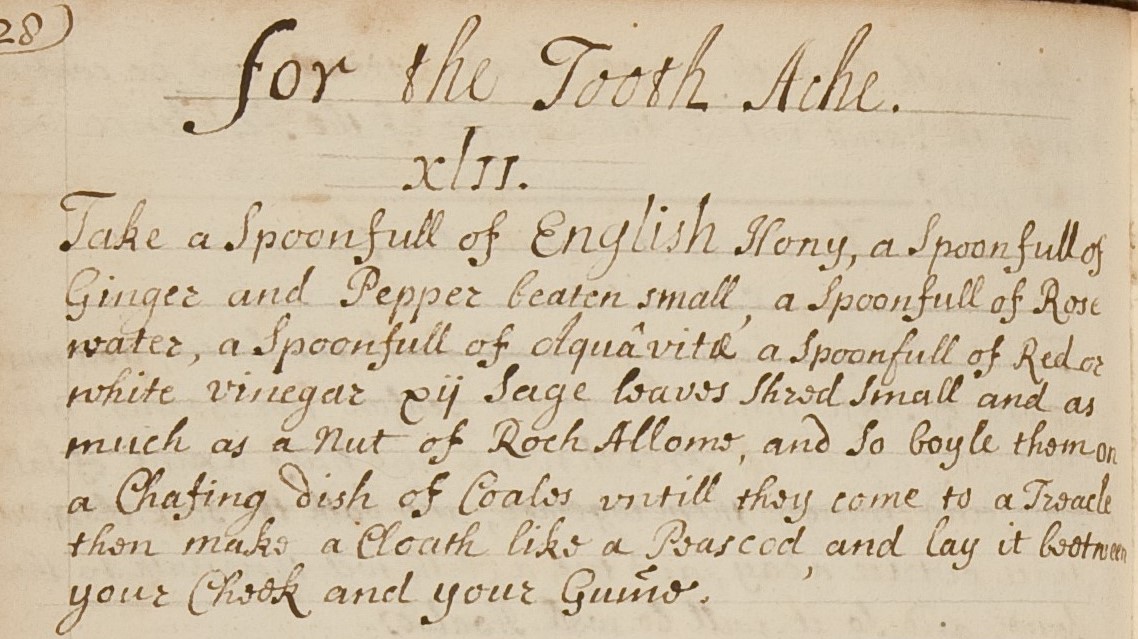

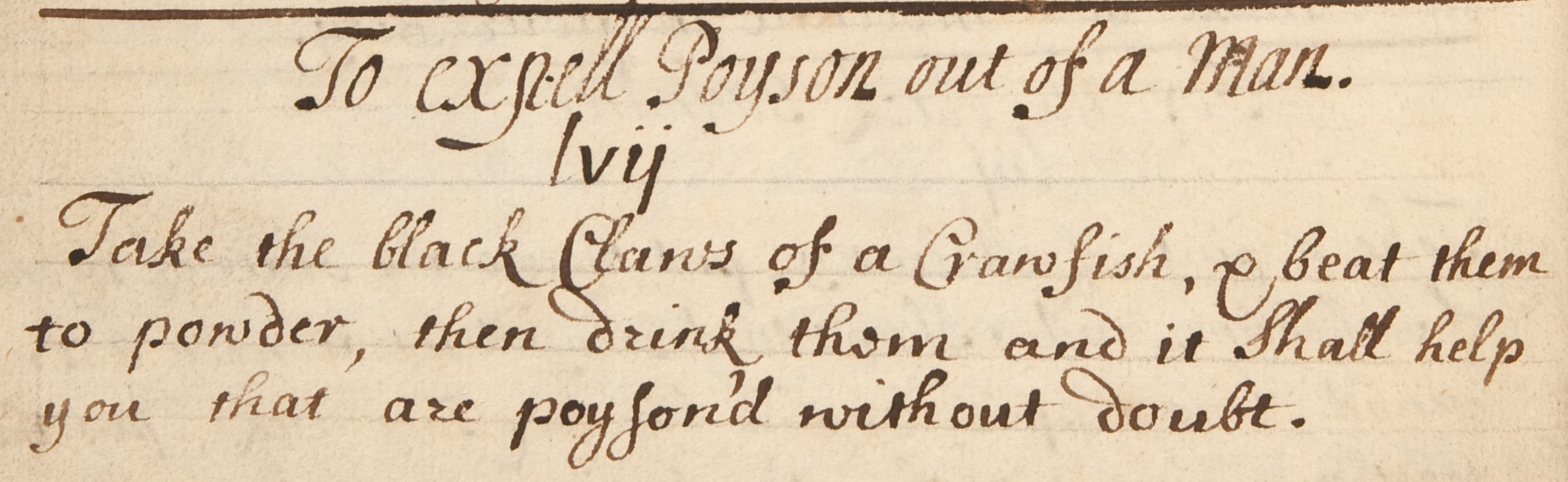

Between the 16th and the 19th century most medical treatments were provided by local healers or from within the household. In higher status households, and in larger population centres, there was access to apothecaries who could make up medicines. More usually, medicines would be made at home from locally available ingredients. They relied on sets of instructions, called receipts or recipes. These could be sourced from well-known healers, or sourced from or endorsed by physicians.

The first recorded use of the word receipt was for a medical preparation in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (c. 1386). The term recipe didn't arrive until the 1500s, and it was also first used to describe medicine. Both words began to be applied to cooking only in the 18th century, after which recipe slowly became the preferred word. Both receipt and recipe are thought to come from Latin recipere "to receive".

In households where the family were wealthy enough to have received some formal education, the receipts themselves were recorded in handwritten books, sometimes combined with more general cooking recipes and other snippets such as estate accounts, poems, or even charms to ward off witchcraft. Because these manuals for medical care were used across generations and kept within families there is often almost no identifying information about the compilers, their locations or what time periods they refer to.

There is sometimes an inscription with a name, a place name, or a date. But it is often impossible to use the inscription to correctly identify a known historical person. This is partly due to the idiosyncratic nature of the inscriptions and partly due to the fact that the author was usually a woman. Women are poorly represented in the historical record, compared to men of similar social status.

The composition of the books, the nature of the common ingredients, the references to sources for the recipes, the style of the handwriting, other types of entries, they all give us clues as to the location, social status, educational status and general lives of the compilers. But these clues can be misleading, for many reasons. In the absence of firm data, the best we can do is make guesses about who the authors were and when they were writing or using these volumes.

Most of the ingredients used in the recipes in this manuscript are plant based, or from animal products. They also follow established medical tradition in the late 1600s. Goat’s blood is used in a remedy for the stone. Doctors of the time thought goat’s blood was lithontriptic (a substance that dissolves kidney stones in the urinary organs). A recipe for the gripping of the gut applies a hot poultice to the navel. Medicines were thought to find a way to the intestines through the navel and were often applied externally rather than internally.

At first glance the identity of the compiler is obvious. Catherine, the wife of Sir Charles Sedley, infamous restoration libertine and poet, was alive in 1686. However, research confirms that from 1672 to her death in 1705, Lady Sedley was being held in a convent at Ghent, with severe mental health issues. Catherine’s daughter, also called Catherine, was a mistress of King James II’s and a celebrated wit at court. He made her Baroness Darlington and Countess of Dorchester in January 1686, so she would be unlikely to have called herself Lady Sedley.

A more likely possibility is that it was written by Ann Ayscough, daughter of a Yorkshire gentleman. Ann became Sir Charles’ common law wife around 1672, after Lady Catherine was sent to Ghent. There are contemporary sources which state they went through some form of marriage ceremony and that she was known socially as Lady Sedley. Charles and Ann had 2 sons and their relationship lasted until Sedley’s death.

A final mystery is that the later recipes, from page 59, are obviously written in a second hand, which is less neat than the first. But there is no second inscription in the volume.

Our archive catalogue is fully searchable online here. While the archive service is closed during the pandemic, a publicly accessible digital copy of this manuscript is available here. Digitized versions of over 10,000 items from our archives are available online, as part of a charged for scientific archives resource.

Pamela Forde, Archives Manager

Resources used in writing this post:

- 'Dictionary of National Biography', Vol.LI, Sidney Lee (ed.) (London, 1897) [DNB, 1897, pp.185-88], entries for Catharine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester (pp.185-87) & Sir Charles Sedley (pp.187-88)

- 'The Lady Sedley's Receipt Book, 1686, and other Seventeenth-century Receipt Books', Leonard Guthrie, 'Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine', 1913, Vol. VI, pp.150-169

- 'Correspondence: Lady Sedley's Receipt Book', Eleanore Boswell, 'Times Literary Supplement', 12 December 1929, p.1058

- Dame Sarah Cowper’s diary, Hertfordshire Record Office D/EP/F29-35

- Sir Charles Sedley, 5th Baronet [Accessed January 2021]

- The history of Parliament, Sedley, Sir Charles, 5th Bt. 1639 - 1701 [Accessed January 2021]

- Merriam Webster dictionary, 'Recipe' [Accessed January 2021]

Lady Sedley's recipe book has been chosen for inclusion in a Transcribathon hosted by the Early Modern Recipes Online Collective, alongside a contemporary recipe book from the Wellcome collections. For full details of the Transcribathon event, see here.