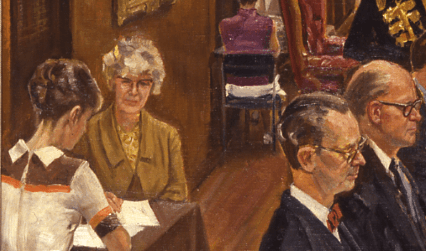

Women are scarce in Raymond Piper’s 1968 group portrait of RCP fellows attending their Annual General Meeting (AGM). Of 89 figures depicted by Piper, just seven are women. Four provide administrative support and are stationed down the painting’s left hand side. Their position behind a flank of senior officers disguises the authority of Ina Cook (1909–1996), who alone gazes wryly out towards the viewer through sharply angled spectacles, dressed in a brown mac.

From 1934 to 1969 Cook dragged the archaic RCP into organisational order. Through decades of efficiency and tenacity, she stormed the last bastion of medical masculinity, not as an RCP fellow (as her 1968 portrait companions Dame Albertine Winner, Dr Elizabeth Stokes and Professor Dame Sheila Sherlock did) but from the position of assistant secretary and later secretary: the first woman employed by the RCP.

A transcript of Cook’s recorded reminiscences is held in the RCP archives and the 15 pages of typed notes are a delightfully engaging read. Cook demonstrates a remarkable sense of humour about RCP life, without which it’s hard to see how she could have withstood the rank awfulness of the early 20th century workplace for women.

Born in Fife, Cook found few openings for women graduates after study at the University of Edinburgh, and came to London. She applied for the job of RCP assistant secretary in 1934 and was interviewed by RCP president Viscount Dawson of Penn, and then registrar Sir Raymond Crawfurd who ‘explained that he himself kept all minutes and records and dealt with correspondence in his own hand. He did not see what I could possibly do, perhaps I could knit? (I couldn’t)’.

Despite this shortcoming, Cook got the job and arrived one September morning in the RCP’s Pall Mall East home in Trafalgar Square (today’s Canada House). Described as ‘more mausoleum than headquarters’ and ‘very small, very grand and very inert’, there was no proper office and Ina took possession of the small library.

Cook writes: ‘I began with a gaffe. I hung my outdoor things on a peg in the hall. Scandal! A wardrobe was immediately built so that this evidence could be suitably hidden’. She remembered that ‘Amenities for ladies … were situated in a housemaids’ cupboard on the back stairs, with a basin on the stairs themselves’.

At that time the College staff consisted of Mr Barlow the secretary, and Mr Bishop, the assistant librarian, apart from porters and one aged porter’s wife’. Mr Barlow explained that ‘he did not want an assistant at all. He had wanted a typist of his own so I should expect no help from him. And this he stuck to until he retired.

The treasurer, Sidney Phillips, was over 80 years old and kept all the books in his own illegible hand until he became blind and needed the auditor to help him. One of Ina’s duties was to listen to the treasurer’s stories of how he caught a spy and his experiences as a special constable. ‘I would be hopping from one foot to the other trying to coax him to sign cheques’.

Internal communication was poor:

I had a telephone, there was one in the Censors’ Room, one in Mr Barlow’s office and a switchboard in the hall. The porter was in charge of the hall and the switch was a very old man and dozed most of the day in the porter’s chair… Dr Phillips when he required anything first telephoned, then blew down a tube which whistled in the hall, then proceeded to the top of the stairs and clapped his hands, and finally shouted.

‘No one kept any records… and I was to start a filing system’. With Dr Phillip’s ‘connivance’ Ina cleared some shelves, very much against the wishes of the registrar who was ‘against filing’ but in time ‘came to see its uses’. At that time there were around 500 fellows so when Comitia (now known as the AGM) was called or there was a circulation all the envelopes had to be typed. Ina did this twice and then asked for an addressograph. Her next request was for a duplicator as all memos had to be typed with carbons several times. At last this was agreed and the RCP moved one step nearer efficient administration.

Some of Cook’s reflections might still resonate today: ‘One of my duties was to, as far as possible, dissuade Dr Phillips from rushing off at a tangent. He was very old and mischievous’.

From noon I was in charge of the Reading Room while the assistant librarian had lunch. This was by no means arduous and I usually read the Times. It was stipulated, however, that I must not go up a ladder… We had two regular readers… Sir Humphrey Rolleston who sat in the far window in his overcoat and ate sandwiches… the other was chatty but later transferred his allegiance to the Royal College of Surgeons as it was warmer there.

Relations with Mr Barlow, the secretary, remained strained up until his retirement.

He would have liked to get rid of me and tried very hard. Some mornings Sam, one of the porters, would be sweeping at the very end of the pavement, to warn me that the secretary was out for my blood… Mr Barlow and I had a shouting match and things went on as before.

The modernising move from Trafalgar Square to Regent’s Park was eventually made in 1964. On the final evening at the old building a candlelight and champagne party was held in the Censors’ Room and the handful of staff, led by Cook, travelled to Regent’s Park (where today over 400 are employed). Cook was responsible for the ceremonies, the laying of the foundation stone by Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother and the opening of the RCP building by Queen Elizabeth II in 1964.

Cook retired in 1969 after 35 years of service. She was the indisputable authority of RCP life, recognised with an MBE and election to honorary fellowship. Her Munk’s roll obituary rather damns with faint praise: ‘She was a sound administrator, although perhaps rather old fashioned. It was impressed on everybody that the punctilious traditions of the College should be observed’. Old-fashioned perhaps, by later standards, but Cook’s legacy as a tenacious trailblazer dragging a decrepit institution into the modern era can be remembered with gratitude today. She spent her retirement in Brighton with her life-long friend Ellinor Grant.

Emma Shepley, senior curator

Comitia, 1968, by Raymond Piper can be viewed online at Art UK. It is on permanent display on the RCP’s second floor public gallery.

A transcript of Ina Cook’s 1987 reminiscences (from which all quotes are taken) is held in the RCP archive (MS2028/37).