Questioning the ‘diagnostic dolls’

Chinese ‘diagnostic dolls’ that depict under-clothed or naked young women lying in relaxed poses and carved in ivory, are found in many Western medical museums. The narrative around them usually describes them as a medical tool used by Chinese physicians before the 20th century for indicating afflicted areas during the diagnosis of women patients. Here in the collection of the RCP Museum, two examples can be found:

S179 Chinese carved ivory diagnostic doll on a wooden mount, 19th century

S430 Chinese diagnostic doll of carved ivory, 19th century

In recent years, scholarship has suggested that they may not be medical related. In this blog, I will share some of my doubts regarding their function.

During the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1636-1913) dynasties, influenced by the widely adopted Confucianism belief system, physical contact between an unrelated man and woman was not allowed in China, even during medical examinations. This seems to be a perfect justification for the existence of such dolls. However, in Yi Xue Ru Men (Introduction to medicine), a Ming dynasty medical book compiled by physician Chan Li (dates unknown), he gave a standard procedure for diagnosing women patients:

‘If diagnosing a woman, a close relative must be asked of her symptoms and her colour of tongue. If her illness is severe, examine the patient across the curtain of her bed; If her illness is mild, examine the patient across the curtain of her bedroom door. A piece of gauze must cover her hand (during the pulse examination), if her family is poor, the doctor will prepare the gauze himself.’

Cheng Congzhou (dates unknown), a doctor in the late Ming dynasty, documented a similar process where a male family member acted as a middleman, passing messages between doctor and women patients. Since no direct conversations were allowed between doctors and women patients during that time, the purpose of these dolls seems dubious.

Another thing that is problematic to me are their configurations. In Ming and Qing dynasty China, anatomical images existed often in forms of Ming Tang Tu (The Illuminated Hall Chart) and acupuncture dolls that show acupuncture points and channels. In these images, human bodies (generally male) were presented in an upright gesture with their genitals omitted or covered by clothing. However, diagnostic dolls depict nude women, posed in a sexually suggestive way. It would be inappropriate for doctors, who were highly respected at the time, to carry them around and present them to others.

Qing dynasty acupuncture figure, Science Museum

Ming Tang Tu (The illuminated Hall Chart)

The human body, showing a circulatory system (?) and acupuncture points: four figures. Colour woodcut (?) by a Chinese artist Wellcome Collection

Many of the diagnostic dolls are similar in style, or even identical in design. This suggests that they were once mass-produced. So, if they were not made for a medical purpose, what were they made for?

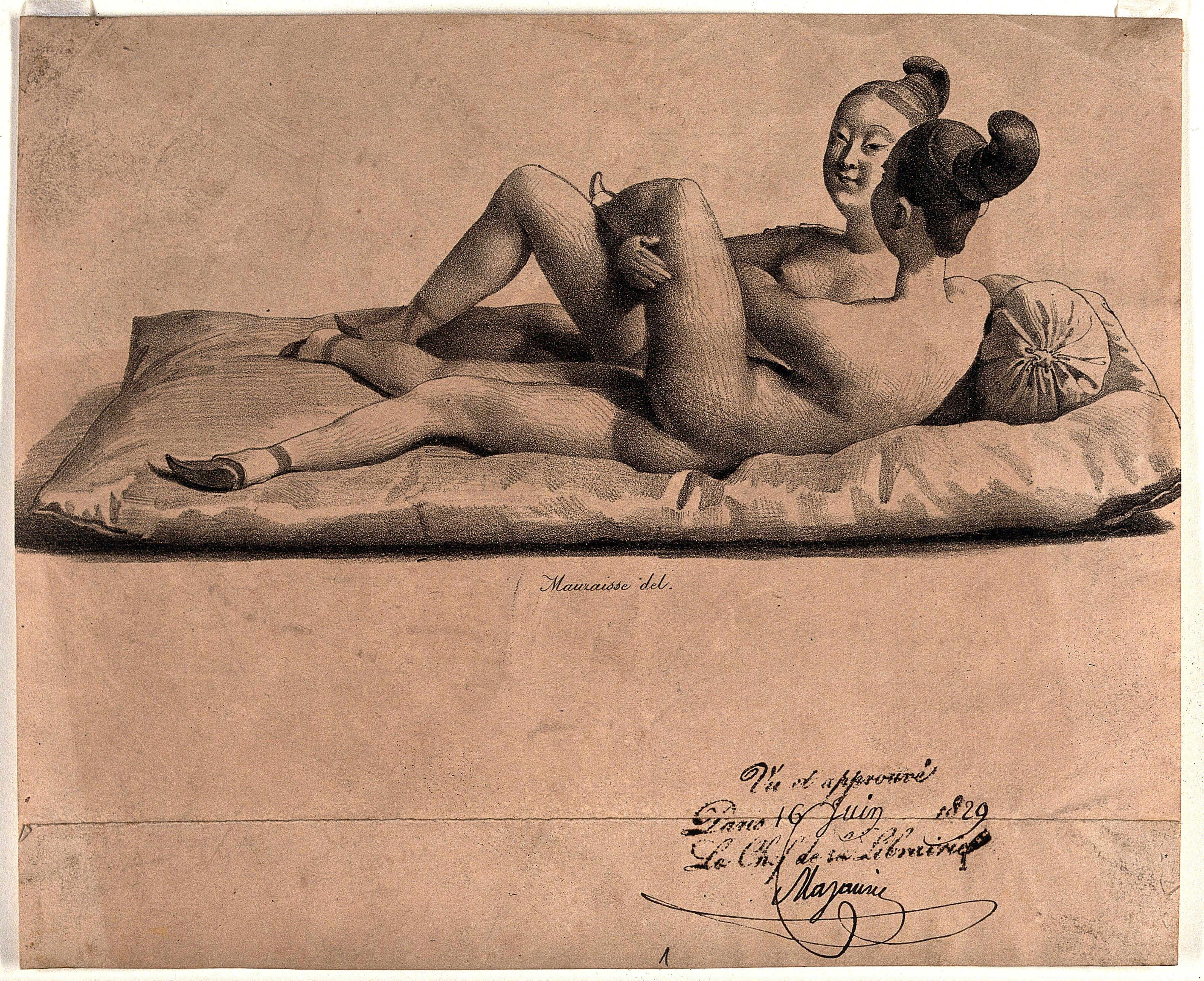

Two Chinese girls with bound feet, J.B. Mauzaissse,1829, Welcome Collection

The true function of these dolls may lie in the time of their production. During the Ming and Qing dynasty, China began to manufacture ivory carvings for western consumers with factories set up in Zhangzhou, and later in Canton [Guangzhou]. These ivory dolls, with their erotic poses and their bound feet, could be products designed exclusively for European customers to meet their expectations of an exotic representation of the east. This would explain why they mainly exist outside of China, and the medical stories behind them, might just be a way to justify their existence among a doctor’s collection.

Yuewei Wang, Placement Student

References:

Furth, Charlotte A Flourishing Yin: Gender in China’s Medical History, 960-1665, University of California Press, 1999

Li. Chan, Yi Xue Ru Men https://www.zk120.com/ji/read/622?uid=None (Accessed on 27/8/2021)

Objects in RCP collection:

S179 Chinese carved ivory diagnostic doll on a wooden mount, 19th century

S430 Chinese diagnostic doll of carved ivory, 19th century