While working with the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital Collection (MS-NORFN), I found the highlight of my placement with the Royal College of Physicians (RCP): a letter from the 1st Duke of Wellington which offended the county of Norfolk (ALS/W61). This may seem like an odd highlight to pick when working with such a well-established and respected organisation, but it perfectly represents what I, and many others, find so enjoyable about working with archives.

To put this into context, I am a student aiming to be an archivist, and so I must complete a two-week placement in an archive. This placement was complicated by the fact it happened in the middle of a national lockdown in response to Covid-19. However, our placements went ahead and I found myself digitally working with the RCP, examining a collection of letters which form the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital Collection (MS-NORFN). The focus of these letters is the Norfolk and Norwich Musical Festival and I read many letters accepting and declining invites, making donations, and offering support written by the Lords, Ladies, Earls and Dukes of Norfolk and beyond. The festival was set up in 1824 to raise money for the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital. Although it traces its history further than 1824, this was the year the festival was formalised into the event which continues until this day. The 1824 festival was a classical music event which had the patronage of many influential and wealthy people in society, including King George VI and the 1st Duke of Sussex, Prince Augustus Frederick. The success of this event amounted to £2,399 being donated to the hospital and ensured that further festivals were held in the future. The festival continued as a triennial event until 1989, when it became an annual event.

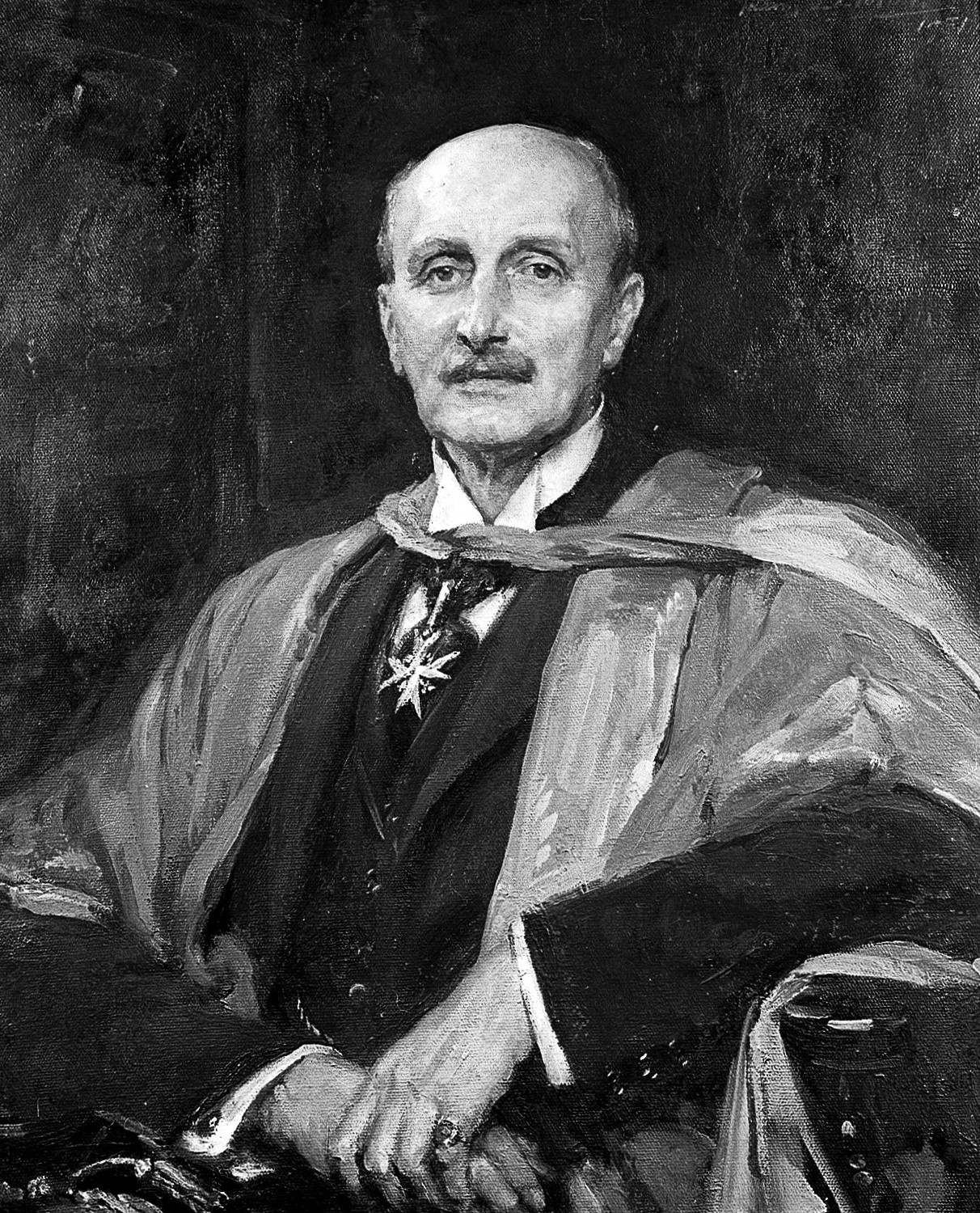

Archiving is not just going through records one by one. Perhaps it is proof of being a history graduate, but one of my favourite parts of archiving is providing the records with context, which means we get to do research. We do this so that we best know how to represent the records, such as finding a suitable name for the collection, or identifying the key people involved. Only through such research can we properly describe the records, as we discovered when we learnt the donor of the records, “Dr Copeman”, may not have been Edward Copeman (1809-1880) as we assumed, but possibly his relative Dr Sydney Arthur Monckton Copeman (1862-1947), both Fellows of the RCP. We had assumed Edward Copemans’s involvement due to the fact he was elected physician in Norfolk and Norwich Hospital in 1851, and appointed chairman of the Norfolk and Norwich Musical Festival in 1857, both positions he stayed in until retirement in 1878, two years before his death. It was in these positions that Edward presumably obtained the collection of letters. However, one of the letters has been recorded as being donated by Sydney Copeman and other letters date from after Edward’s death. Due to this, we believe there is a possibility Edward passed his collection onto Sydney, who added further letters to it, before finally donating the letters to the Royal College of Physicians. Regardless of which Copeman donated the collection, both were successful in their fields, with Edward being a specialist in gynecology and Sydney advancing military medicine.

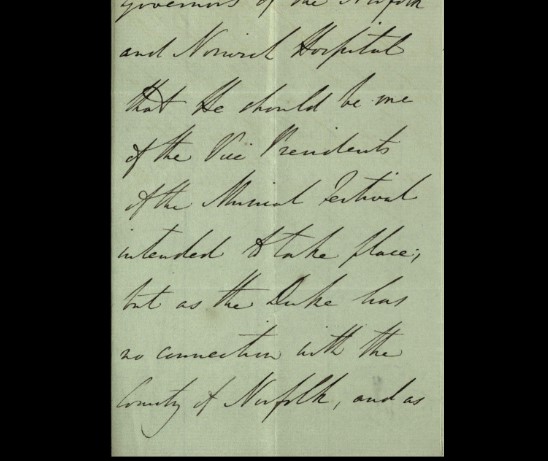

Archival research took me from the website of the Norfolk and Norwich Musical Festival, looking over information concerning the Festival's 250th anniversary, to a book published in 1896, directly informed by some of the people involved in the original festivals. From this research, we are able to produce a well-informed description of the collection, noting the first festival raised £6,833, was conducted by Sir George Smart (1776-1867), and my highlight, that a letter I had examined (ALS/W61) caused a little scandal at the time. This is because the Duke of Wellington declined an invitation to be a Vice President of the Festival as he had “no connection with the county of Norfolk” (ALS/W61), an excuse which did not go down well with those in support of the charitable festival. The Committee organizing the Festival demonstrated through a not-so-subtle response that they disapproved of his excuse, reminding him of his “presence… at the grand battues [hunts] of the late Lord Suffield, and his acceptance of the freedom of the city”, a rather clear display of the Duke’s connections to the county.

While my placement was a little strange, working through Zoom and emails due to the Pandemic, it still represents the basic but crucial work of cataloguing that most archivists wish they had the time to do. Being able to handle (albeit electronically) and read over records from the past is what attracts many to the profession; I began my relationship with archives in a search room looking over 19th century records for my dissertation. It is this type of hands-on engagement with records which can change history from the abstract to the real, allowing us to see in his own words how the Duke of Wellington offended a whole county across just three small pages.

Shea Evason, Archives placement student

Sources used:

- Norfolk and Norwich Hospital Collection (MS-NORFN)

- Autograph letter from Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington to John S Patteson, Mayor of Norwich (ALS/W61)

- Norfolk and Norwich Music festival at 250 [Accessed January 2021]

- Robin Humphrey Legge and W.E. Hansell, Annals of the Norfolk & Norwich Triennial Music Festivals, Jarrold and sons, 1896 [Accessed January 2021]