Medals and plaquettes (small rectangular plaques) are frequently overlooked in museum collections, but often reveal hidden depths if you take a closer look.

Medals have a very long history, but they first became common in the 15th century. Commissioned by rulers and nobles with their portrait on one side and usually their coat of arms or emblem on the other, they were designed to be given as gifts to allies or as a way of currying favour with someone more influential. As time went on people began to create medals for other reasons, such as to commemorate events or for propaganda purposes.

Later medals built on this tradition, and the RCP Museum collection holds medical medals from the late 19th century to the present day, most of which were donated to the museum by members and fellows of the RCP. What the medals were awarded for, who they were from, and what they depict can give us a unique insight into what – and who – physicians have considered important over the last 150 years.

The apparatus of medical life

The intricacies of day-to-day life may not be something you would expect to see on a specially commissioned award such as a medal, but the apparatus of medical life makes an appearance on several of the RCP’s medals.

The Richard Mead medal was a prize awarded to students at St Thomas’ Hospital in London. It was engraved and probably designed by two members of the Wyon family, well known engravers in London in the 19th century, Leonard Charles Wyon (1826–91) and Allan Wyon (1843–1907). With a head and shoulders portrait of Mead on the front, the back shows a man sat on a stool, deep in thought.

Behind him on a desk we can see – if we look closely – the equipment of medical and scientific research. The coat of arms of St Thomas’ Hospital Medical School hangs on the wall, while to the left, below the window, is a microscope, accompanied by a flask with two tubes poking out of the top and looking as though it has just been detached from some large experimental set-up. To the right is an incubator, used to keep laboratory samples dry and maintain them at a constant temperature. If you look past the figure in the foreground you can see a pot containing hooks and a scalpel, items that would have been used for anatomical research and dissection, and possibly those that the figure has recently used to extract the heart which he is contemplating, holding it – glove-less – in his left hand.

Excelling in examinations

Many medals were produced to celebrate the achievement of an individual. This set of unusual plaster medals in metal cases were awarded by the Royal Manchester School of Medicine and Surgery for performance in university medical exams. William H Broadbent (1835–1907), son of a Yorkshire factory owner, attended Manchester medical school, graduating in 1857. Evidently a conscientious student, Broadbent received these medals during his three year degree for ‘excelling in the examinations’ in Chemistry (1855), Materia Medica, Medical Botany & Therapeutics (1855, an extra summer course), Anatomy and Physiology (1856), Principles and Practice of Medicine (1856), Principles, Practice and Operations of Surgery (1857), and again in Anatomy and Physiology (1857).

The development of the Manchester students’ medical knowledge can be seen from the courses taken by Broadbent; first year includes modules in chemistry, botany and the ingredients used in medicines, before later years moved on to focus on the more practical and interventive elements of medicine such as surgery and the workings of the body.

The retention of the set together by Broadbent suggests the pride he must surely have taken in being awarded these marks of recognition during his studies. His early achievements led to a very successful career that included positions as physician to various member of the royal family and to being awarded a baronetcy in 1893.

Étienne-Jules Marey

From general images of medical research to more specific depictions; a small number of items in the collection show named individuals carrying out their work. Étienne-Jules Marey (1830–1904) was a French physiologist who carried out research on the circulation of the blood. Alongside Auguste Chaveau he invented the sphygmograph, an instrument for measuring the pulse, in 1859. The small machine sits along the length of the wrist, over the pulse point, the small movements of the pulse causing a thin metal arm on the sphygmograph to bounce which in turn draws a line on the attached piece of paper. This early version of a blood pressure monitor is the basis of equipment still used today.

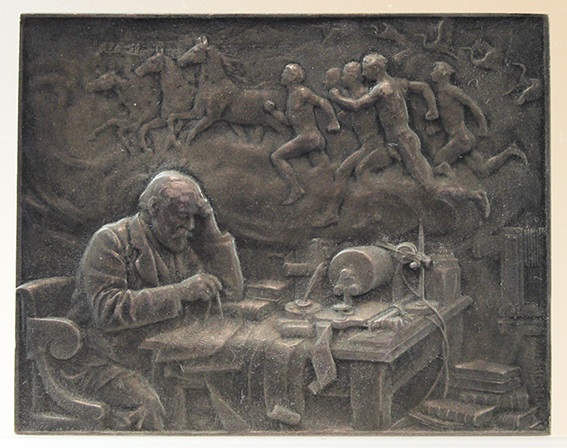

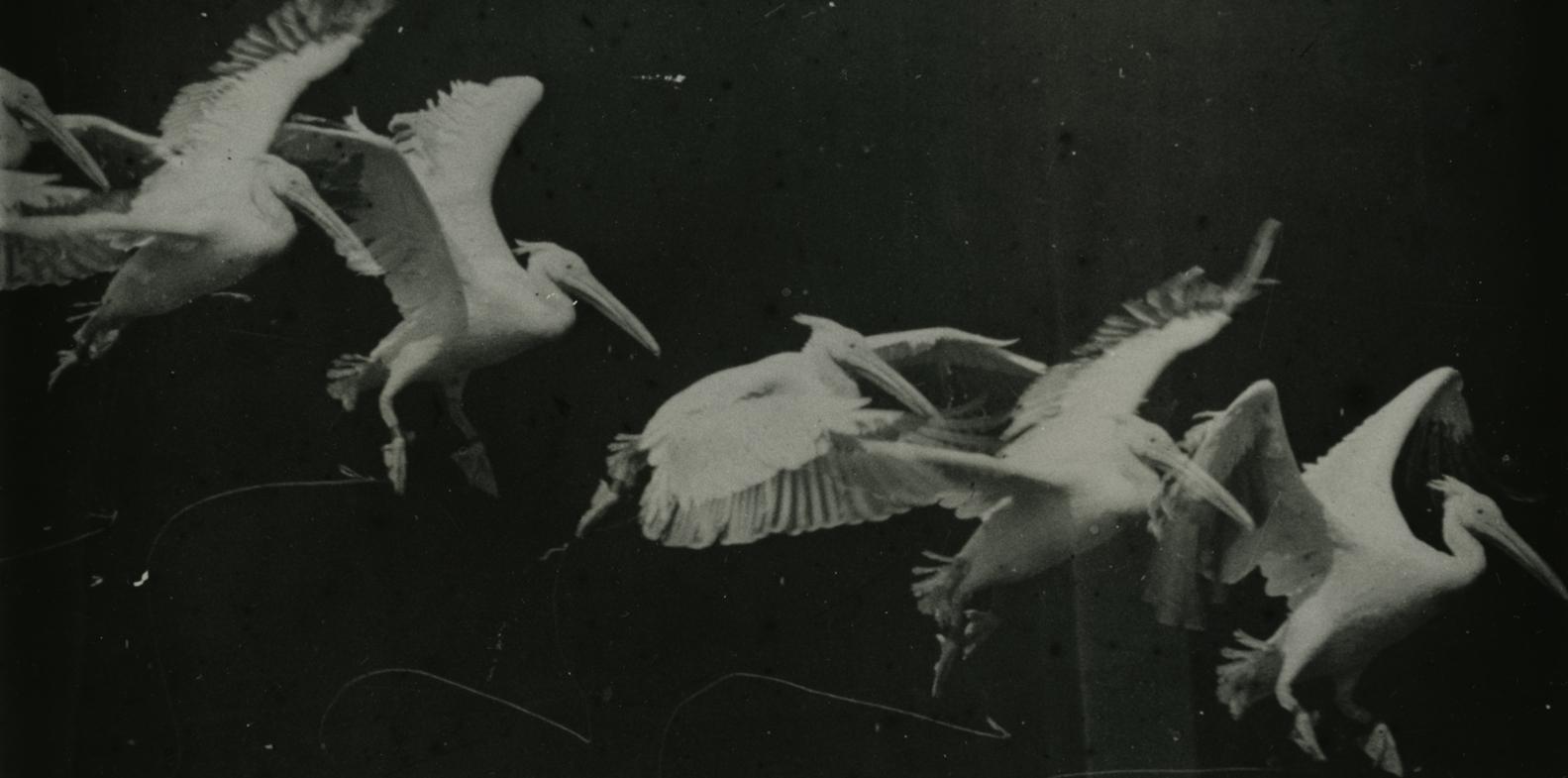

In addition to his work on blood pressure Marey researched the functions of motion, studying an extensive array of animals as well as humans and even developing a special ‘photographic gun’ to enable him to take images of birds in flight. The plaquette – a commemorative metal item similar to a medal but rectangular – of Marey in the museum collection was designed by Paul Richer in 1902. It commemorates Marey and his work, showing on the obverse (front) a portrait of Marey and an inscription specifying his position on the staff of the Collège de France, a long-standing higher education and research institute in Paris.

The reverse again shows Marey, but this time sat at his desk, deep in thought over some calculations that he is conducting with the aid of a pair of compasses. There are books stacked on the floor and his workspace is piled high with paper traces from measuring equipment that takes up most of the table space. On the far right is visible a cinematic machine, referencing another strand of his research that looked at how to capture and display moving images. The top half of the image depicts, in a cloud-like thought-bubble, running men and horses, flying pelicans, and a scene with steamboats on a lake tucked into the top left corner, indicting the subjects of Marey’s studies into motion and blood pressure.

Explore the RCP coins and medals collection further by browsing our catalogue.

Lowri Jones, senior curator

Medical Medals is a small permanent exhibition that can be visited in the Thomas Cotton room on the lower ground floor of the RCP. The RCP building is currently closed due to the Coronavirus outbreak but updates will be posted on our Visit Us page when we are able to welcome visitors again.