For 8 weeks in March and April Cara Gobea joined the Library, Archive and Museum team on a work placement during a semester studying in the UK. While she was here, she helped to list a collection from the RCP archives.

The lives of many great men and women who made medical discoveries and aided those in need are connected with the RCP. A prime example of one of these characters is Lord Max Rosenheim (1908–1972), former RCP president. The RCP archives hold several of his letters to colleagues, personal journals, and hundreds of photos from his medical voyages around the world.

Uncovering the life of Lord Rosenheim, one is bound to be amazed by his dedication to medicine and his contribution to developing countries. He began his research and experiments on the use of mandelic acid as a treatment for urinary infection in 1932, which became the focus of his doctoral thesis in 1938. The success in his research led to several other discoveries for the use of mandelic acid as a treatment and gave him a jump-start on his career as a research medical doctor. If it wasn’t for this discovery RCP and the rest of the world may not have heard of Max Leonard Rosenheim. The news of his discoveries reached beyond the UK, making its way to the United States of America, whose doctors honoured Lord Rosenheim through letters and enquiries about his ground-breaking discovery.

The Raymond Horton-Smith Prize for the best MD Thesis of the year was awarded to him in 1938, giving him the opportunity to be recognized by several doctors locally and others from other regions, such as New Orleans, USA. Among his correspondence one will find enquiries from doctors associated with the American Medical Association seeking more information on the medical uses of mandelic acid, along with aid to their experiments.

After the publication and success of his treatment for urinary infection, Rosenheim spent much of his time traveling around the world studying new medicine, attending conferences, and working to improve healthcare and medical education in developing countries. His first voyage was to the USA in 1939 and he continued on into his old age where his last adventure was in Mauritius, Cape Town, and South Africa in 1972.

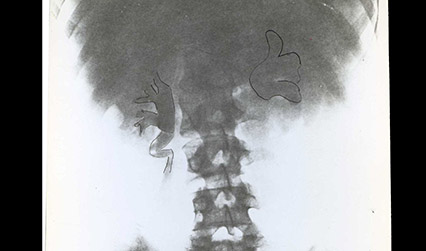

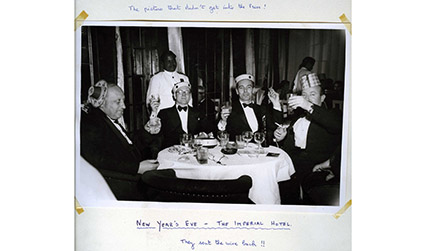

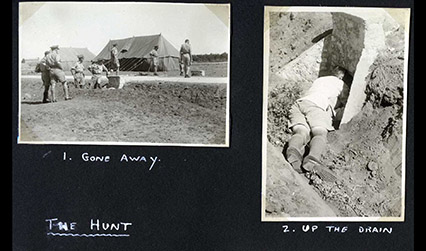

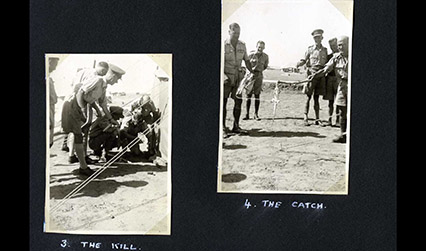

He was awarded the Bilton Pollard Travelling Fellowship in 1939 and placed under Dr Fuller Albright (1900–1969) in Massachusetts, but his time was cut short. Rosenheim was called for a greater purpose and returned home to London, to assist in the war. In 1941 he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and was positioned as officer-in-charge of the medical unit in various regions such as the Middle East, North America, Europe, and South Asia. The Rosenheim collection is filled with correspondence, notes, and his own personal form of scrapbooking up until 1941. However form 1941–44, we have nothing but a photo album holding pictures of his medical unit and the places he was stationed. This photo album sheds a bit of light on the mysteries of war with bits of personal captions and heart-touching photos of injured soldiers making do with what they can.

From there on, Lord Rosenheim continued discovering the world through the eyes of medicine. He maintained several travel diaries for every voyage he embarked on, each with detailed notes – right down to what he ate for dinner! He was a man who paid close attention to detail, with timings and activities carefully recorded. He assisted in the Colombo Plan in India in 1955, a regional organization that focuses on intergovernmental effort to assist the economic and social development in the Asia-Pacific region, and went on to even larger organizations, like the World Health Organization. He mostly helped teach students and fellow doctors new practices of medicine, bringing new technology to poorer nations.

It is in his photo albums where you see glimpses of his personality and sense of humour, which is often sarcastic. Several of these albums contain his own comments and adventures, such as a lizard chase in the midst of war. Lord Rosenheim had an eye for photography. Although he is generally recognized for his brilliance in medicine, it would not be so farfetched to esteem him as a photographer as well. Several of his photos beautifully capture the life around him, even in what would be considered a time not to remember.

Within his collection it is evident that he was a well-respected doctor, as well as a loved friend. Rosenheim had a gift with people, where his patients did not feel as just his patients but more of a colleague or even a friend at times. He was even viewed as a friend to Winston Churchill and his wife, Clementine Churchill. Among several other letters thanking and praising Max Rosenheim, one will come across a few letters from Winston and Clementine Churchill where one can see the obvious fondness they held towards Rosenheim. His aid to the Churchills brought about their friendship, where Clementine Churchill would wish him, “a wonderful time in America,” and send thanks for the roses he sent and an evening at a delightful performance.

Among these praises there are whole files on his becoming a Lord and being placed on the Queen’s Birthday Honours list. He received so many letters of congratulation from his colleagues, patients, and important figures that they could be a whole collection in themselves.

Cara Gobea, archives intern