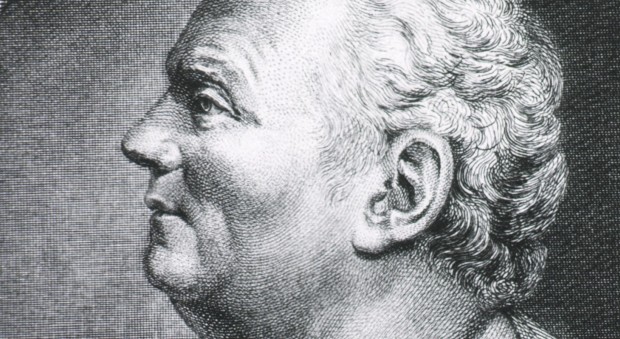

On 30 May 1765 in Philadelphia, John Morgan (1735–1789), a young physician newly arrived home after a 5-year long trip to Europe, began to deliver a speech at the commencement ceremony of the College of Philadelphia outlining his proposals for a new medical school, the first in the American colonies.

Earlier that month he had been appointed as America’s first professor of the theory and practice of medicine by the board of trustees at the College. The speech, his first public opportunity to describe his ideas, was later published as A discourse upon the institution of medical schools in America (1765), a copy of which is available in the RCP library.

Early life

Morgan was uniquely suited for his pioneering role. Born in Philadelphia in 1735, the son of Evan Morgan, a wealthy merchant and property owner, and Joanna Morgan née Biles, from a prominent Quaker family, he had what was then the best medical education available in the colonies. Between 1750 and 1756 he served as an apprentice to John Redman, a physician at Pennsylvania Hospital, and studied at the College of Philadelphia, graduating with a bachelor of arts degree. He also gained practical medical experience, spending a year as an apothecary at Pennsylvania Hospital and 4 years as a military surgeon in the French and Indian War.

European studies

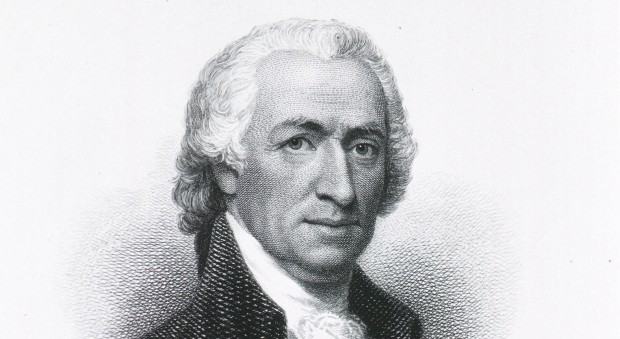

Recognising that many senior physicians in Philadelphia had studied in Europe, in 1760 Morgan resigned from the Army and sailed to England to continue his education. In London, he registered as a pupil at St Thomas’ Hospital and was also a student of William Hunter (1718–1783), the anatomist and physician, who taught him how to make anatomical preparations by injection and corrosion. Morgan then went to Edinburgh, where he studied with William Cullen (1710–1790), the renowned physician and chemist, and in 1763 gained an MD, having written a thesis in Latin on the formation of pus.

Morgan left Edinburgh for Paris in late 1763, where he attended the lectures of the eminent surgeon and anatomist, Jean-Joseph Sue (1710–1792). From Paris, Morgan rounded off his education with a Grand Tour of Italy and Switzerland, an adventure he recounted in The journal of Dr John Morgan of Philadelphia from the city of Rome to the city of London 1764.

When he returned to Philadelphia, Morgan was possibly the most qualified – and honoured – physician then in the colonies. In addition to his MD, he was a corresponding member of L’Académie Royale de Chirurgie in Paris, a licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians of London, and a fellow of the Royal Society and of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

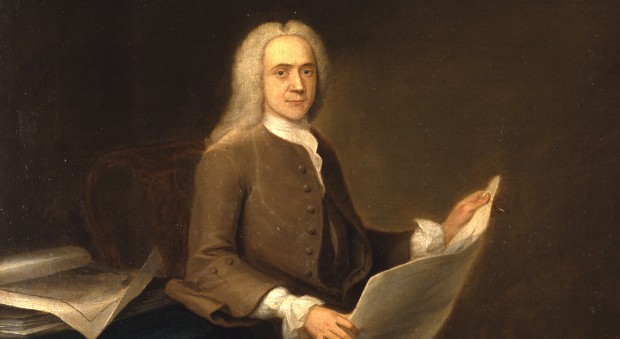

He also brought with him a unique set of recommendations and medical connections. The politician, writer and scientist Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790), then based in London, was a family friend and had introduced the young doctor to the prominent Quaker physician, John Fothergill (1712–1780). Fothergill had in turn put the sociable Morgan in touch with other leading physicians in London and in Edinburgh. By the time Morgan returned to Philadelphia, his proposal freshly written, Fothergill, Hunter and William Watson (1715–1787) had all given their support to the idea of a medical school.

School of medicine

There was also wide support for the medical school among the community of young American doctors and students Morgan had met in London and Edinburgh. In particular, he talked to a Philadelphian young physician, William Shippen junior (1736–1808), about his plans. Like Morgan, Shippen studied at Edinburgh University, but returned to Pennsylvania before Morgan and, in 1762, began a series of lectures on anatomy. In September 1765 Shippen was made a professor of anatomy in the new medical school, three months after Morgan’s appointment.

In the commencement speech, Morgan began with a defence of his then novel decision to practise as a physician in Philadelphia and not as a surgeon or apothecary. In this, he was following the newly introduced rules of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. Since 1750, the Edinburgh College had barred anyone who was already a member of the Corporation of Surgeons, and 4 years later resolved that fellows must not practise as apothecaries.

Morgan then outlined what subjects should be taught in medical school. These should be studied in a certain order as ‘links of a chain … begin with Anatomy; then what I have called medical natural history, viz The Materia Medica and Botany; Chymistry should follow; and the study of practice should compleat the work’.

He then described the state of medicine in the colonies. Although, as he pointed out, there were physicians and surgeons ‘qualified by genius, education, and experience’ many American practitioners were, he (rather tactlessly) argued, undertrained and ill prepared, their actions ‘robbing the affectionate husband of his darling spouse … increasing the number of orphans; – mercilessly depriving them of their parent’s support’.

Philadelphia, he went on, was the logical choice for the location for a medical school. The city was growing in population and influence, and already attracted young men wishing to study medicine. The Pennsylvania Hospital was an ideal place for clinical teaching and medical students would be able to study other subjects at the College and gain a good liberal education.

On 26 September 1765 the Pennsylvania Gazette printed the formal announcement of the opening of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Morgan’s course on materia medica and chemistry began on 18 November and met three times a week for three or four months, initially in the back parlour of his house. Nearly three years later, on 21 June 1768, ten students were given the first MB degrees in America and, in 1771, the first doctorate in medicine was conferred.

The medical school grew rapidly, but over the years a serious rift developed between Morgan and Shippen. Shippen, who had been the first to offer public lectures to medical students in Philadelphia, not unnaturally felt the idea of a medical school was his own. Morgan certainly downplayed the younger man’s contribution in his commencement speech, pointing out that though Shippen had ‘proposed some hints of a plan for giving medical lectures’, he hadn’t recommended establishing the new school within the College of Philadelphia.

The antagonism between the pair continued into the American Revolutionary War. In October 1775, Morgan was appointed by Congress as director-general to the military hospitals and physician-in-chief of the American Army. During his short term in office he faced insubordination, problems with supplies and a continual undermining of his position. Shippen led a faction attempting to oust him from his military role, and in 1777 Morgan was dismissed and Shippen appointed in his place. Two years later, after lobbying Congress and writing his pamphlet A vindication of his public character in the station of director-general of the military hospitals, and physician in chief to the American Army, Morgan was absolved of all wrongdoing.

After the war, the pair refused to work with one another. Morgan retained his professorship, but never again taught at the medical school. Worn down by ill health, the conflict with Shippen and the battle to clear his name, his once promising career faded. He resigned his post at the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1783 and, after the end of 1786, rarely saw any patients.

Morgan died alone in his house from influenza on 15 October 1789, aged 54. The death notice which appeared in some American newspapers as well as in London’s Gentleman’s Magazine highlighted his transatlantic achievements as ‘... one of the Medical Professors in the College of Philadelphia, and member of many literary societies, both in Europe and America’.

Sarah Gillam, assistant editor Munk's Roll

Read our weekly library, archive and museum blog to learn more about the RCP’s collections, and follow @RCPmuseum on Twitter and @rcpmuseum on Instagram.

The following sources were used when writing this post:

- Bell WJ. John Morgan: continental doctor. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1965.

- [Editorial]. John Morgan (1735–1789) founder of American medical education. JAMA 1965; 194(7):235-236.

- Flexner A. Introduction. In: Morgan J, A discourse upon the institution of medical schools in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1937.

- Middleton WS. John Morgan, father of medical education in North America. Annals of Medical History 1927; IX(1):13-26.

- Morgan J. A discourse upon the institution of medical schools in America: delivered at a public anniversary commencement, held in the College of Philadelphia May 30 and 31, 1765. Philadelphia: William Bradford, 1765 https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/A_Discourse_upon_the_Institution_of_Medic... [Accessed 14 June 2017].

- Packard FR. Morgan, John (1735–1789). In: Kelly HA, Burrage WL, American medical biographies. Baltimore: The Norman, Remington Company, 1920. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/American_Medical_Biographies/Morgan,_John [Accessed 14 June 2017].

- University of Pennsylvania Archives. Penn biographies: John Morgan (1735–1789). http://www.archives.upenn.edu/people/1700s/morgan_john.html [Accessed 14 June 2017].