Have you ever picked up a second-hand book and found someone’s name written inside? It’s enticing to stop and imagine who they were, and what life they led. What did they do with their time? Did they have a long life or a short one? Did they enjoy the book and keep if for years? Or was it given away at the first opportunity?

This often happens when I’m cataloguing a rare book: previous owners’ names appear on title pages, flyleaves and endpapers. Trying to untangle the handwriting and determine the spelling of someone’s name can sometimes be an insurmountable task. But sometimes, the pieces all fall into place and we find a connection to someone’s life, work and biography.

This week I’ve been working on some of the cataloguing backlog: books donated to or bought by the RCP library over the last few years. A handful of them are very relevant to our current exhibition Under the skin, all being anatomical in nature.

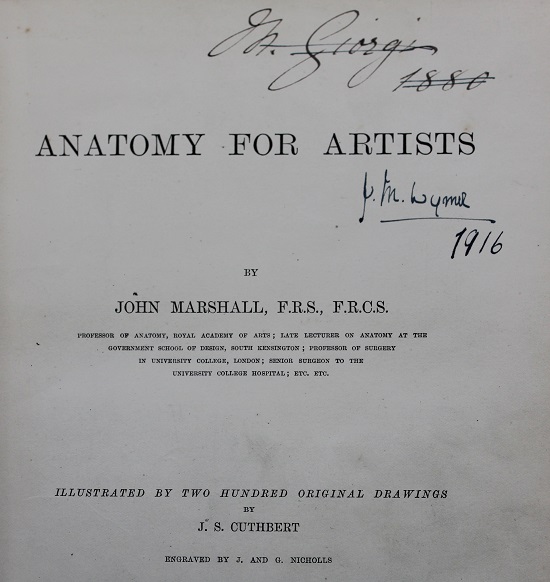

One book had clear signs of previous use and ownership: Anatomy for artists (1878) has a name written on the title page in pen, dated 1916.

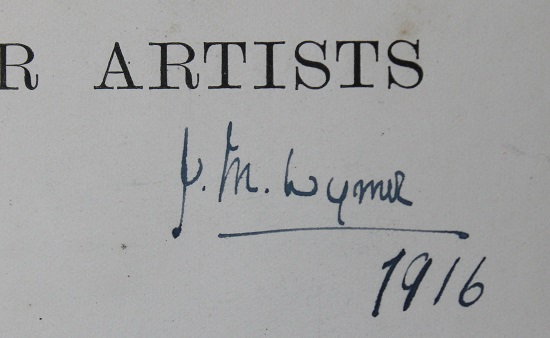

But what did it say? Wynne? Wynen? Leyner? The more you look, the harder it can be to be certain. Without any further corroborating evidence, the trail would go cold at this point. But our mystery owner wrote their name three times: on the title page, and on the blank pages at the beginning and end of the book. They sometimes added an address: 34 Stanhope Road, Sidcup, Kent.

Armed with these details and our best guesses at the name, we were able to track them in the 1911 census, and lo and behold, a Jean Mason Wymer is found at that address.

Searching online for Jean M. Wymer reveals that she was an art student at the Royal Academy schools from 1922 to 1927. In 1924 she married fellow art student Cosmo Clark, and changed her name to Jean Clark. Jean and Cosmo lived and worked in New York, London, Broadstairs, and the West Midlands. After Cosmo’s death in 1967, Jean moved to Suffolk. She painted in oil and watercolour and completed several murals for churches and other institutions. She exhibited across the country, with a retrospective of her work at the Bankside gallery, London in 1983.

Wymer was born in 1902, so she was only 13 or 14 in 1916 when she first signed the book. She was by then already studying at her local art school in Sidcup Kent, and had her sights set on studying at the Royal Academy (RA) in London. We can certainly assume her artistic ambitions were already well in train, because this certainly isn’t a children’s or beginner’s book. It’s over 400 pages long, full of technical language and detailed anatomical information.

Wymer's artistic education at the Royal Academy would have required intensive study of the human form, not only the external appearance but also the internal anatomical structure. The curriculum included anatomical lectures alongside close examination and drawing of classical sculpture, live models, and écorché models.

The book itself has a strong pedigree, with text by John Marshall (1818–1891), professor of anatomy at the RA, and illustrations drawn by John S. Cuthbert, Wymer's own maternal grandfather. There’s no evidence that this was a family copy of the book, passed down from John Cuthbert himself: in fact, another unidentified signature, ‘Jn Giorgi, 1880’, on the title page suggests that it probably wasn’t.

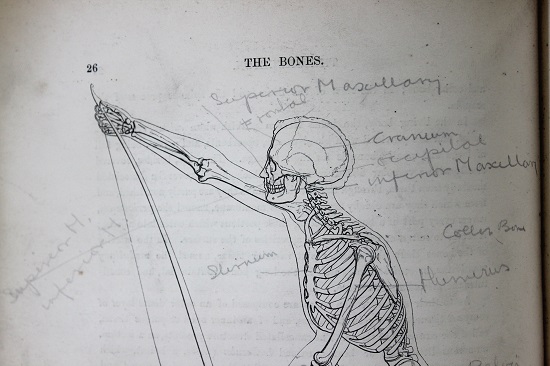

Wymer didn’t just leave her name and address in Anatomy for artists, but also a scattering of notes and annotations throughout the volume. Through these notes we can see the budding artist getting to grips with the human body, labelling major bones from head to toe.

Though her spelling of sometimes leaves a little be desired (she writes ‘stirnum’ for ‘sternum’, the breastbone) it’s clear that she was doing her best to master the details of the skeleton. Her artistic education at the Royal Academy would have required intensive study of the human form, not only the external appearance but also the internal anatomical structure. The curriculum included close examination and drawing of classical sculpture, live models, écorché models, and dissected human cadavers.

I haven’t been able to determine whether any of Wymer's student drawings survive: it would be fascinating to see how practical knowledge developed alongside the theory she learnt from this book.

Katie Birkwood, rare books and special collections librarian

With thanks to Felix Lancashire, assistant archivist at the RCP, and Annette Wickham, curator of works on paper at the Royal Academy of Arts.

Wymer’s copy of Anatomy for artists has now been added to the RCP library collection, and can be consulted in the library reading room. Other recently catalogued anatomical rare books include:

- John Marshall, illustrated by John S. Cuthbert, A rule of proportion for the human figure (1879).

- H. Renlow, edited by John Browning, The human eye and its auxiliary organs anatomically represented (1896)

- Florence Sabin, An atlas of the medulla and midbrain (1901)

- Hubert Biss, Baillière's popular atlas of the anatomy and physiology of the male human body (1948)