This post discusses historical attitudes to race, and quotes language and attitudes considered offensive today.

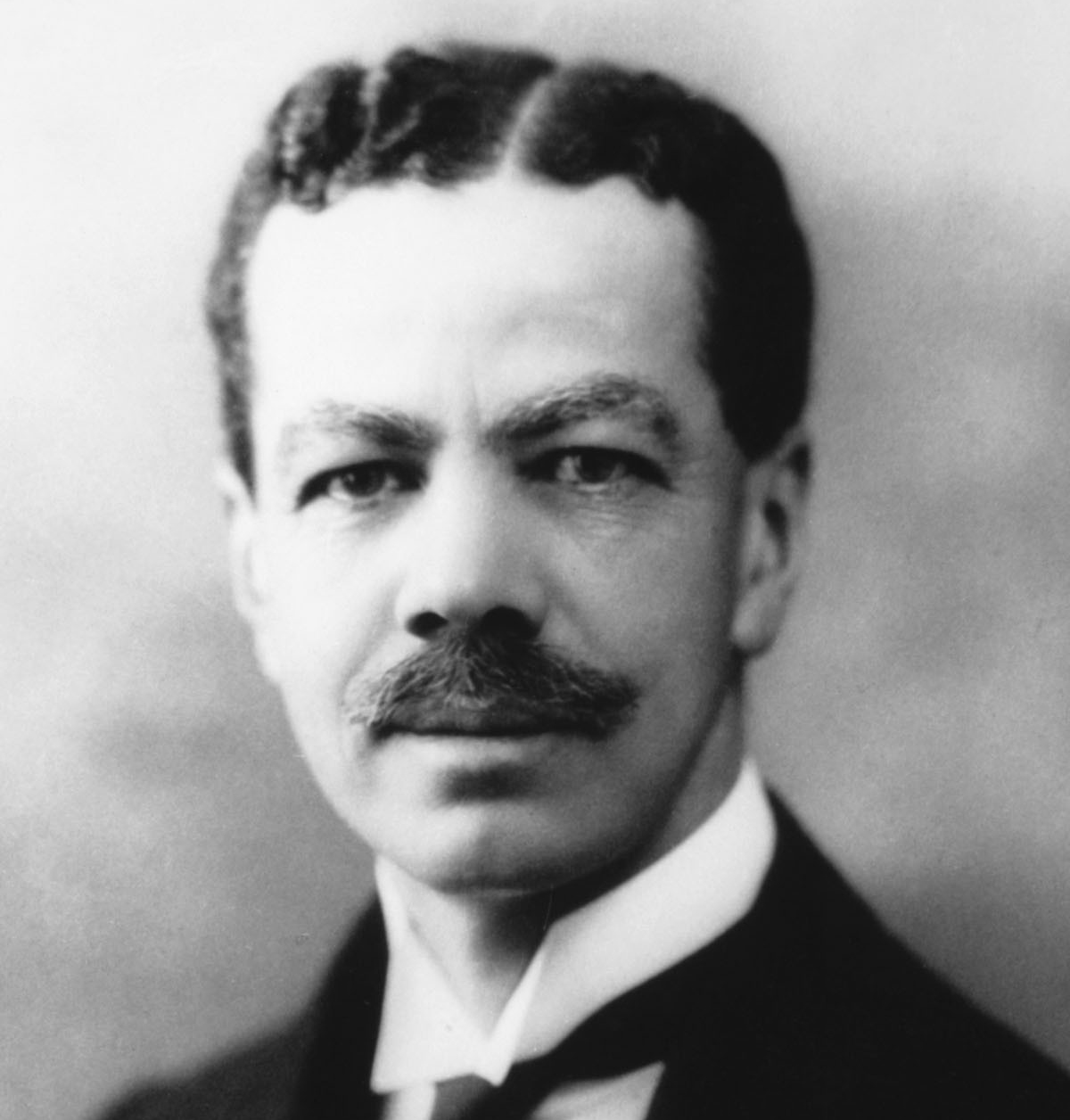

James Samuel Risien Russell (1863 – 1939) was a renowned neurologist, acclaimed professor, and one of the first Black British consultants. He became a member of the RCP in 1891 and was elected a fellow in 1897.

The careers of Black physicians like Russell are an integral part of Britain’s medical history. Often this narrative begins in the era of the Windrush migration after the Second World War. However, by starting here it overlooks earlier, pioneering West Indian doctors.

Russell was born in British Guiana (now Guyana) to a Scottish father and a mother of African descent. His father emigrated to Demerara in 1847 and became one of the wealthiest men in the colony through his sugar plantations. His mother’s history is unknown.

Russell was privately educated in Scotland and studied medicine and surgery at Edinburgh University between 1882 – 1886. He was an exceptional scholar and his Edinburgh Doctorate of Medicine was awarded the gold medal for outstanding achievement in 1893.

Russell completed his postgraduate medical training at St Thomas’ Hospital in London, and in 1895 received a grant to study in Berlin and Paris. While in Paris, he studied nervous diseases under Jean-Martin Charcot, at the Salpêtrière Hospital.

After returning from study abroad, Russell worked in Nottingham General Hospital and at the Metropolitan Hospital, London. In his early career, he worked in the research laboratory of distinguished neurosurgeon Sir Victor Horsley at University College London (UCL).

In 1898, Russell was appointed resident medical officer at the National Hospital Queen Square. His research at the National Hospital contributed to the understanding of the cerebellum and subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord (damage to the brain and spine caused by vitamin deficiency and associated with a kind of anaemia).

Later, Russell took a step back from research to focus upon practice and neurological teaching. As professor of clinical medicine at UCL his students remembered him as a gifted and inspiring teacher, particularly favouring clinical demonstrations over formal lecture. His interest in clinical teaching is reflected by his contributions to Allbutt’s System of Medicine, Quain’s Dictionary of Medicine and Gibson’s Textbook of Medicine.

In 1900, Russell was appointed consulting physician of neurology at the National Hospital. Following this appointment, he became a member of the management board and professor of medical jurisprudence; a branch of medicine that applies medical knowledge to legal situations.

With two important appointments at the UCL and the National Hospital, Russell went on to set up his own practice at 44 Wimpole Street in the heart of London’s private medical district. He specialised in mental disorders and his clients comprised ‘a large proportion of chronic psychotics and psycho-neurotics’. His practice treated some famous clients of the time such as the explorer Sir Henry Stanley and the novelist, Mrs Humphry Ward.

Considering Russell’s career success, it is perhaps tempting to believe that the early 20th century medical profession was free from racial prejudice. Sadly not, with racialised slurs and an inappropriate fixation upon his skin colour is evident in reminiscences by his peers and later biographies.

One of his students recalled how Russell, then a consultant, was belittled by a fellow physician:

‘One day when Dr Taylor and I were going up the stairs Risien Russell and Leslie Paton were chatting in the front hall and, as a high-pitched laugh resounded up the [stair]well, James Taylor said "Russell's little n***o laugh"- the only unkind thing I ever heard him say about anyone.’

M, J. Purdon, Reminiscences of Queen’s Square, 1981

Russell’s ethnicity was omitted from his obituaries but offensive remarks about his appearance permeate later biographies. His house-physician Macdonald Critchley recalled Russell’s ‘dark skin’ (1920) and other accounts referenced his ‘n*****d features’ (1981) or being of ‘mixed racial stock’ (1991).

From 1908 and throughout the First World War, Russell served as a Captain of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). His commission as an officer was unusual as the War Office was known to be hostile to Black doctors, including those trained at British universities. It advised that only West Indian medics of ‘pure European descent’ were likely to be accepted as officers in the RAMC.

It is difficult to ascertain whether Russell’s wartime career was affected by War Office racism and he continued to work as a consultant at the National Hospital treating soldiers with shellshock. After the war, he was active in campaigning for reforms to lunacy laws and campaigned to keep patients with less severe mental health issues out of mental institutions. He became Chairman of the National Society for Lunacy Reform in 1924 and acted as an expert witness in the courts for high-profile cases with psychiatric considerations. In 1928, Russell retired from the National Hospital, completing a 30-year career with them.

Within his lifetime, Russell was a well-known and respected physician. He achieved consultant status and a large private practice. He enjoyed his material success. He was chauffeured about town in his Rolls Royce, owned fine art and hosted dinner parties with a small orchestra.

Russell died in the consulting room of his Wimpole Street practice at the age of 75. This year, the Windrush Foundation nominated his residence and practice to the blue plaques scheme. English Heritage have approved the nomination, publicly marking the life story of Britain’s first Black consultant physician.

Correction: In the original blog article James Samuel Risien Russell: Britiain's First Black consultant (published 7 July 2021), we said that Russell was Britain's first Black British consultant. It has come to our attention, via research conducted at Queen Square Archive, that he was not the very first but one of the first consultants of colour. In fact, Charles Édouard Brown-Séquard (1817 - 1894) pre-dated Russell in becoming a consultant physician. Highlighting the careers of pioneering Black consultants, and physicians of colour, remains an essential and ongoing area of research for the RCP.

Elizabeth Douglas, collections officer

Sources used in writing this post

References [all accessed 16 June 2020]:

- Obituary, James Samuel Risien Russell, Br Med J 1939 ;1: 645

- Brown, G.H., James Samuel Risien Russell, Inspiring Physicians, Vol IV: 396

- Green, J., Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, James Samuel Risien Russell

- Green, J., Dr James Samuel Risien Russell

- Windrush Foundation, Pioneers: Dr J S Risien Russell

- O’Connor, W.J., British Physiologists 1885-1914: A Biographical Dictionary, Manchester University Press, 1991

- MacNalty, A., Some Pioneers of the Past in Neurology, Medical History, 1965

- Purdon Martin, J., Reminiscences of Queen’s Square, Br Med J 1981: 1640-42

- Imperial War Museum, Lives of the First World War: J S Risien Russell

- Costello, Ray, Black Tommies: British Soldiers of African Descent in the First World War, Liverpool University Press, 2015

- Linden, S.C., and Jones, E., Medical History, October 2014: Volume 58, Issue 4, 'Shell shock' Revisited: An Examination of the Case Records of the National Hospital in London