When we go back in time to the 1600s, instructions are basic and measurements are more indicative of relative ratios than precise amounts. Then we come to the elements which are really subject to variations. The temperature of the heat source (the fire), how well items have been pounded in a mortar, the freshness of the organic ingredients, the alcohol content of the ale or wine etc.

How did someone using a recipe know that they achieved the desired result which would make the remedy as intended, and therefore, hopefully an effective one? If a recipe book was complied by a local healer and passed on to a successor or peer, it is more than likely that the book was more of a teaching aid. Most of the training would have been practical, with skills learned on the job. One of the skills being passed on would be the knowledge of what the remedy should look, smell and taste like.

In general, the more complicated and difficult to produce a recipe was, the less likely it is that it would have been used by the casual reader. But it is very likely that some of these books were compiled and used by people who were healers for their communities. Making remedies could have been a large part of their role. Such people could have routinely used more complicated recipes.

Another compelling piece of evidence for the assumption that these volumes were compiled and used by local people with specific healthcare roles in their societies is the lack of diagnostic content. The recipes clearly assume that diagnosis has already taken place. Making a diagnosis when someone has an obvious injury or set of symptoms could be reasonably straightforward when they are examined. But identifying the cause of symptoms is less obvious with certain diseases. Experience would have been needed for accurate diagnosis.

The term ‘domestic recipe book’ which is usually how these volumes are described assumes a separation between personal and professional healthcare which was not well defined at the time these volumes were being used. The role of a healer was likely part of a network of traditional community organisation in rural communities and small towns. Only larger urban centres would have widespread professional medical services. These would have been too expensive for many of the poorer sections of the community, where simple self-treatment was possibly the only affordable option.

As with so many elements of early modern medical recipes, there isn’t enough historical record we can rely on when researching the use and effectiveness of these fascinating volumes. The full story will always be beyond our grasp.

Transcribathon 2022

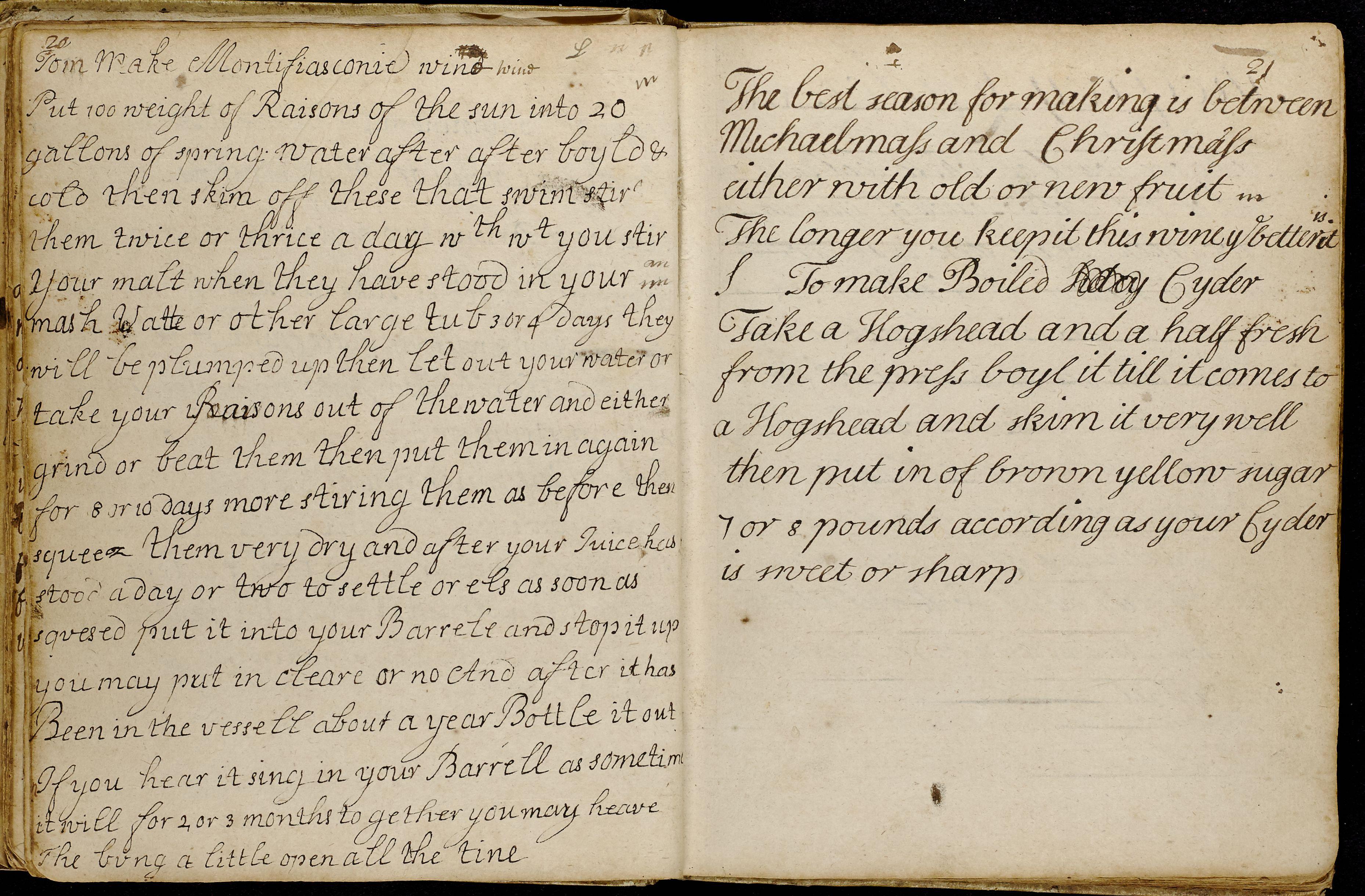

Manuscript MS502, “A collection of medical receipts and prescriptions” is from the archive collections of the Royal College of Physicians. This handwritten volume has been chosen as one of the items included in the EMROC 2022 November transcribathon. This takes place on 4 November 2022. See here for more details and how to get involved.

A complete digital copy of this manuscript is available, in an online collection of RCP medical recipe books, in the Internet archive, here.

To accompany the Transcribathon, we are producing a series of blogs about manuscript 502, focussing on each of the elements which make up a successful recipe. See below for the previous blog in this series.

This is the fourth and final blog in the series. For more information on this, and the other fascinating items which make up the archives of the Royal College of Physicians, see here.

Pamela Forde, archives manager

Discover the story behind the manuscript, what made it a great choice for the transcribathon, its authors and its ingredients in these two excellent videos by archive manager Pamela Forde.