As our exhibition ‘This vexed question: 500 years of women in medicine’ comes to a close, guest curator Briony Hudson, considers the challenges and delights of researching ‘hidden’ history.

Women’s history is often described by historians as ‘hidden’ but what does that mean in reality when you’re planning an exhibition focussing on the role of women in medicine over the last 500 years? If much of women’s work is invisible, how does a curator find material to put on display?

The hidden nature of women’s work often relates to their exclusion from the formal sphere of employment until recent years. This is certainly true for medicine: the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) used the silence on women in its founding documents as its rationale for their exclusion from its membership until the early twentieth century. They were apparently following the lead from an 1511 Act of Parliament that included women as ‘the great multitude of ignorant persons’ that were carrying out ‘the Science and Cunning of Physick and Surgery.’ So women appear very rarely in the College records. When they do it is usually to be reprimanded, often fined and occasionally imprisoned, their punishment often harsher than for male offenders.

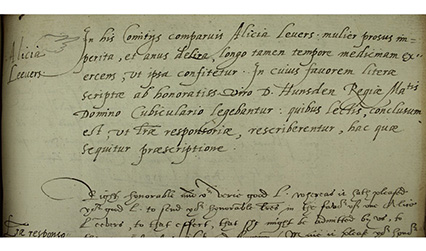

For example, Elizabeth Pratt agreed to cease medical practice on 24 February 1709, signing her name at the bottom of a formal bond in the College’s collection. She admitted treating Mary Morecock for a sore throat with ‘crude mercury’, and charging her 40 shillings. Morecock later died, and Pratt was fined £15 by the College censors and sent to Newgate Prison. In contrast, in 1586, Alice Leevers was saved by her association with Lord Hunsdon, Elizabeth I’s Lord Chancellor. His letter to the College after her appearance there, led to the compromise that she would be allowed to continue to practice even though the RCP records describe her as ‘utterly ignorant’ in medicine.

Of course, many women worked within a family business with their husbands as the visible worker or wage earner in the majority of cases. But this hides multitudes of women who had significant medical skills. Susan Lyons appears in the records of both the RCP and the Society of Apothecaries. Like many widows, Susan Lyon continued her husband’s apothecary business after his death. On 16 February 1631 she appeared before the College censors who banned her from making any more medicines. However, the records note that she ‘keeps her shop as in her former husbands dayes and serveth phisitions bills ... [she] cann and doth make medicines and hath made manye.’ She appears in the records because she supplied medicines to an unlicensed Dutch doctor. However, the Society of Apothecaries allowed Lyon to train her second husband to work alongside her and her apprentice, showing that they recognised her expertise.

Family businesses depended on women as well as men. Examples in the exhibition include Daffy’s Elixir, built up as a successful medicinal brand by its inventor Anthony Daffy in the mid-18th century, but continued by his widow, daughter-in-law and granddaughter. Author Nicholas Culpeper is extremely well-known but it was actually his wife Alice who was responsible for the publication of many works after his death. In 1656 she defended her actions, publishing a ‘Vindication of her Husband’s Reputation’ in The English Physitian Enlarged:

my Husband left seventy-nine Books of his own making, or Translating, in my hands, and I have deposited them into the hands of his, and my much Honored Friend, Mr Peter Cole, Book-Seller, at the Printing-Press, neer the Royal Exchange (for the good of my Child) …

Jane Pemell of Southwark was licensed by the Archbishop of Canterbury to practice surgery on 10 July 1685. Echoing Alice Culpeper’s vindication, Pemell’s application included a personal statement demonstrating both her experience and her need to practice in order to support her family:

I have under god followed this practise about twenty years and have bine very successful in cures haveing nothing else to mayntayne my family, haveing lost all & fyred out of the citty, & my husband being taken in the Dutch wares had lost all hee had goten in seven yeares & both ancient, I weare willing to put myselfe foreward to doe good, and to get an honest mayntenace

However, what marks Pemell out as different to many other women in this period, is that she was an authorised practitioner. The same 1511 Act that provided justification for the RCP to exclude women, set up a system of licensing through the Church of England. The Archbishop of Canterbury granted licenses to 12 women in this way, with Jane Pemell’s poignant testimony on display in the exhibition, generously on loan from Lambeth Palace Library.

What is difficult for the historian is to grasp from these glimpses of women in formal or published records whether they represent the norm. Can we confidently extrapolate from these individuals to come up with a sense of how many women were working in medicine, and what work they were carrying out? From her exploration of contemporary records, historian Margaret Pelling estimates that over 300 women were working as medical practitioners in London in 1550–1640. Surviving advertising handbills from the 18th century, including one promoting Agnodice the Woman Physician on show in the exhibition, suggest that there were many women selling medicines and cosmetics, and carrying out minor surgical procedures, even if they weren’t allowed to formalise this work through registration or membership of an institution.

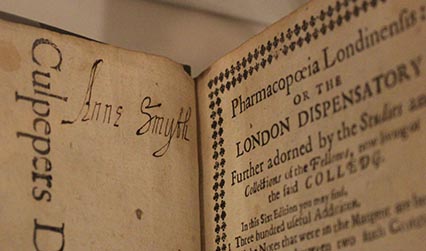

Much of the evidence for women in medicine and in work more widely – and also for other more hidden groups – survives in a very ephemeral form. If they’re not in these rare formal records, the registers of livery companies or depicted in portraits, where do you find them? Instead the sources are often hand-written and paper-based, passed down in families rather than in legal records or corporations. This is certainly the case for women making medicines within their homes, and passing on recipes through receipt books, or marking their name in medical publications, presumably to record their ownership (and readership?) of them.

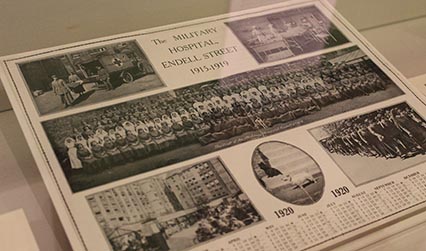

Perhaps surprisingly, this is also true in recent decades: the surviving evidence for women’s work is flimsy and was not necessarily intended to survive. One example on display is the calendar produced to commemorate Endell Street Military Hospital in 1919. Presumably these calendars were produced in great numbers to mark the end of a remarkable period of women’s history: a hospital staffed entirely by women, led by suffragettes Louisa Garrett Anderson and Flora Murray, open from May 1915 to October 1919, that treated 26,000 in-patients and 20,000 out-patients during this short time. But how many calendars still survive? The one on show in the exhibition was saved in the voluminous archives of the Medical Women’s Federation at the Wellcome Library, probably just collected in with other material, a single sheet of thin paper, but a fantastic record of a ground-breaking and short-lived institution.

Another fascinating survival on display is a handkerchief recording the signatures of suffragette inmates at Holloway Prison in 1912, an item that has moved from ephemeral to highly-treasured through its life. Information about its early existence is virtually non-existent: having been signed by 66 suffragette prisoners, including GP Dr Alice Ker, presumably within the jail, it must have been brought out by one of the women involved, and later embroidered so that the signatures survive. It was re-discovered in recent decades and is now preserved as part of the Priest House, part of Sussex Archaeological Society.

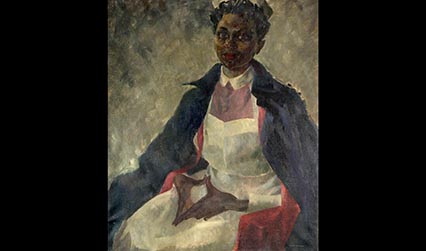

Even when we do have records of women working in medicine, that information is often extremely scant. Nurse Brown from Jamaica is a portrait in the exhibition, loaned by Wolverhampton Art Gallery. It was painted by Irene Welburn in around 1956, and its title provides the only information that we know about this sitter. She was part of the Windrush generation recruited to the NHS after the Second World War, but no other information seems to have survived.

Incredibly, even women achieving ‘firsts’ can prove elusive. The first woman member of the Royal College of Physicians was Ivy Woodward (1877–1957), who joined in 1909. Trawling through census records and medical registers has allowed us to flesh out her biography, including her posts at the Royal Free Hospital, the New Hospital for Women, Warneford Hospital, Belgrave Hospital for Children, and as Medical Inspector for Infant and School services. We can find details of her marriage to surgeon Arthur Haslam and their 5 children. However, we have been unable to find a single photograph of her. For the exhibition, we have commissioned artist Mark Conlin to produce a silhouette to represent her likeness, but we would dearly like to add a real image to the college’s collection. Can you help?

Briony Hudson, guest exhibition curator

The RCP exhibition This vexed question: 500 years of women in medicine closes on Friday 18 January 2019.