In their work, physicians strive to combat death. In the 19th century, death was much more a part of everyday life than it is today, leading to mourning practices which may seem strange to 21st-century eyes. But what happens when it is a physician themselves who dies? Inspired by a recent discovery in the stores, this post explores the practice of post-mortem photography and Victorian end-of-life care.

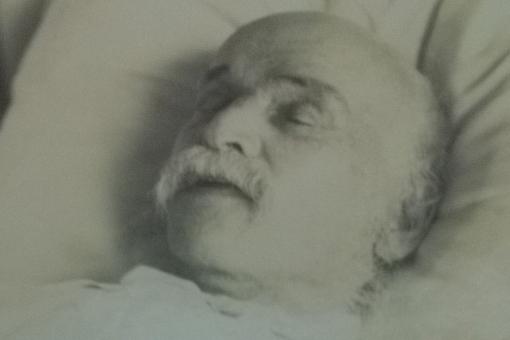

At this time of year, thoughts turn to the ghoulish and the macabre. When during a recent project we came across two post-mortem photographs in the museum stores, we knew that deathbed photography would be the perfect subject for the season. The photographs show famous Victorian doctor Sir William Jenner (1815–1898), physician-in-ordinary to Queen Victoria from 1861 to 1889. Yet rather than depicting Jenner in his ceremonial finery, this emotive image shows the great physician on his deathbed.

Post-mortem photography was a popular mourning practice in mid-19th century Britain and America, reaching its peak around the 1870s. While it may seem macabre to us today, portraits taken after death were an important way for families to remember lost loved ones. In the 1840s, photographers even advertised their willingness to take pictures of a deceased loved one ‘within an hour of their death’. When such images were commissioned they were often displayed prominently on mantelpieces in the home. These post-mortem photographs were intended to capture the ‘last sleep’: showing a relative at peace to comfort the grieving family. Such images are predominantly of children, often representing the only picture a parent would have of their child. From the 1880s, mortality rates began to improve, leading to a decline in popularity for post-mortem photography.

These images show Jenner in a characteristic ‘last sleep’ pose. His bed has been pushed into the centre of the room, likely allowing space for a photographer to position themselves in front of a curtained window. As there were personal cameras available in the 1890s, it’s possible this photo was taken by a relative rather than a professional photographer. Rather than being shown in a coffin and surrounded by flowers, this photograph was likely taken very shortly after the hour of Jenner’s death.

William Jenner was a Victorian celebrity, rising quickly through the ranks and becoming physician-in-ordinary to Queen Victoria in 1861. The next year, Jenner famously treated Prince Albert after he contracted typhoid, the disease which ultimately resulted in his death. Jenner was an expert in typhoid and wrote a famous volume on the subject of distinguishing the infection from the very similar typhus. As Jenner had mused in life: ‘The great aim of the physician is to prevent disease; failing that, to cure; failing that, to alleviate suffering and prolong life.’

The deathbed photos of Jenner raise a number of interesting questions: why were these photos taken when post-mortem photography was on the wane? Indeed, it is much more common to see deathbed photographs of children gone before their time than someone who had lived a long and full life like Jenner. Furthermore, why would a physician who spent his life fighting against death be depicted in such a way after his passing?

These post-mortem photos of Jenner fall into the tradition of memorialising famous individuals after their death; that these images were given to the RCP suggest they were intended as a record of the famous doctor. While his celebrity may have waned in the years since his retirement in 1889, Jenner was a well-respected physician who had been elected RCP president in 1881. Many of the most famous post-mortem images in the world are of deceased world leaders, such as Vladimir Lenin.

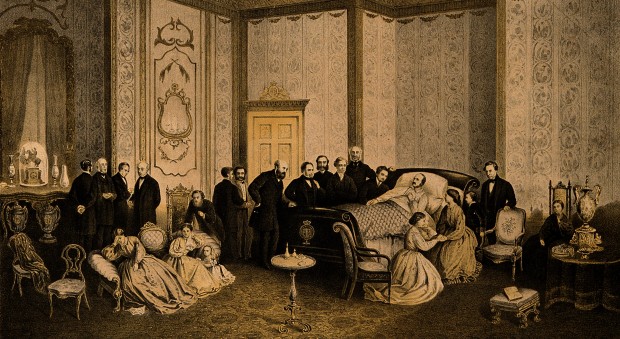

Underlying these photos is a broader issue – that of the role of the physician in death and end of life care in the 19th century. Doctors played an important task in ensuring their patients had a ‘good death’ in the Victorian era. A good death was typically understood to be when the patient’s friends and family had time to say goodbye and the patient could pass-on peacefully. It was crucial that physicians provided an accurate prognosis, alerting friends and family to the nearing event and allowing the patient time to see to their worldly affairs.

While Jenner had believed it was the role of the physician to ‘prolong’ life as long as possible, at the time of his death, medical opinion was changing. Sir Henry Halford (1766–1844) and William Munk (1816–1898) were just two of the prominent physicians who were transforming attitudes towards end-of-life care. Munk in his famous Euthanasia or, Medical treatment in aid of an easy death (1887) encouraged physicians to alert patients and families to the nearing event as soon as possible, while keeping the patient as comfortable as possible, using heavy doses of opium where necessary.

For the relief of pain in the dying wherever it may be situated, we have our one trustworthy remedy in opium … If judiciously and freely administered it is equal to most of the emergencies in the way of pain that we are likely to meet with in the dying …

Both Munk and Halford believed in the importance of alleviating pain in terminal cases, and argued that opium addition was not a concern in these cases. The same stance was taken decades later by Dame Cicely Saunders (1918–2005), pioneer of the hospice movement.

While we may not know who took the photograph, these post-mortem images of Jenner appear to have served their purpose. They are an immediate and striking image of a leader of the profession in the 19th century – a memorial to his life and a reminder of his humanity.

Kristin Hussey, curator

- Portraits of Henry Halford and William Munk are on public display on the second floor gallery of the Royal College of Physicians. For more details on items in our photographic and print collections, search the collections online.

Read our weekly library, archive and museum blog to learn more about the RCP’s collections, and follow us on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.