Tracing the history of women in any field is notoriously challenging: a combination of tracking down biographical details from brief mentions, extrapolating from individual stories to attempt to reconstruct the wider context, and interpreting the meanings behind a lack of evidence.

But every field also contains pioneers, and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836–1917) is perhaps the most well-known woman doctor in medical history. Hers is certainly not a 'hidden history'; instead significant surviving sources provide researchers with ample details of her life, career and opinions. She is also commemorated through institutions, plaques and activities that perpetuate her fame and achievements.

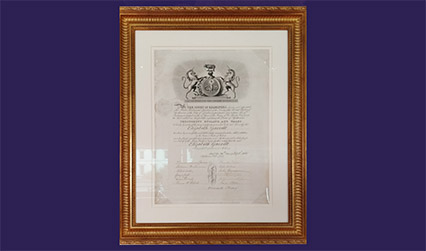

Having set her sights on achieving a medical qualification, and having been rejected by the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) in 1864 in her attempt to take their exams, Elizabeth qualified as a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries on 28 September 1865. Her qualifying certificate is on display in our current exhibition ‘This vexed question’, as is her 1864 letter to the RCP President requesting that she be allowed to take the College’s exams instead of the ‘comparatively easy mode of entrance’ presented by the Apothecaries.

But what is her wider legacy in terms of primary sources, historical evidence and surviving material? Where else can a researcher turn to explore the life of this determined professional, passionate mentor, and committed campaigner?

The RCP holds a small number of items relating to Garrett Anderson in its collections, most notably letters and petitions sent to the College. They show her developing from a medical student to a significant figure in the medical world, and her continued campaign to achieve educational parity for women medical students and doctors. The contrast between Elizabeth’s controlled handwriting and vocabulary in her initial letter of 5 April 1864 and the flourish of her signature on an 1895 petition to request woman be allowed to join the RCP membership is marked, but the response from the college was equally negative on both occasions. The small card asking for permission to attend a lecture of the Harveian Society on 25 November 1887 reinforces the point that Garrett Anderson, by this time well-established in the medical field, could not assume that her presence would be welcome.

Unsurprisingly, there is also surviving material in the archives at the Society of Apothecaries. The iconic survival is her qualifying certificate, lent to the exhibition, but this is backed up in their collection with the fascinating record of her experience, training and attendance at lectures that allowed her to sit their exams.

Once she became established, her roles in the hospital she founded and the London School of Medicine for Women (LSMW) where she held the post of Dean from 1883 mean that her documentary trace is much greater and formalised. Most of the relevant collections are held at the London Metropolitan Archives including photographs, formal LSMW archives such as minute books and student records, and letters to and from Garrett Anderson.

As an establishment figure, she was captured in a magnificent portrait by John Singer Sargent in 1900 held at the National Portrait Gallery. However, one biographer provides details of her reluctance to be captured as a ‘national treasure’, disagreeing with Singer Sargent over his depiction of her hands as too delicate, wearing a cheap pearl necklace in response to his request for her to wear jewellery, and insisting on wearing her academic gown rather than something more dressy. What she would think of the portrait being on permanent display as the only woman sitter in the Victorian Science and Technology Gallery?

More recently, she has been commemorated in a dedicated exhibition gallery at the Unison building on Euston Road. Fittingly, the exhibition makes use of the surviving remains of the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital building which neighbours the modern Unison headquarters. The Hospital was originally the New Hospital for Women, opened in 1872 as the successor to Garrett Anderson’s St Mary’s Dispensary, which she first opened in 1866. The New Hospital was re-named the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital in 1918, after her death the previous year. Its closure, first threatened in 1976, was highly contentious and vigorously opposed by many, a campaign that can be retraced through the papers of both the Hospital and its Staff Action Committee held at London Metropolitan Archives.

Garrett Anderson’s name survives in the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson wing of University College Hospital and the Garrett Anderson Centre at Ipswich Hospital. Her aspirational career has also inspired a NHS leadership development programme and a girls’ school in Islington. She is also commemorated in a blue plaque at 20 Upper Berkeley Street, London, her home between 1865 and 1874.

With so many achievements in the medical world, it’s easy to overlook Garrett Anderson’s political career. As a high-profile feminist and supporter of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), she took part in suffragette events and activities until 1911 when she stood down in opposition to their arson campaign. Her younger sister Millicent Fawcett was, of course, a leading campaigner for the moderate suffragist movement. Garrett Anderson was also the first woman to hold the office of mayor, elected in 1908 in her home town of Aldeburgh, Suffolk. The town is justifiably proud of its connection, with a plaque marking her family home, and another in the church, where she was buried in 1917.

Briony Hudson, guest exhibition curator

This vexed question: 500 years of women in medicine opened on 19 September 2018 and runs until 18 January 2019.