This blog post looks at the end of the life of Ruth Harris (1926–1980), who died from cancer in 1980 before she could be awarded fellowship. Her nomination, made by Council (part of the RCP’s governing body) not long before her death, was withdrawn by that same body after her death. This was despite the precedent of other physicians being awarded fellowship posthumously. Had she lived long enough, Harris’ fellowship would have been awarded at Comitia, the RCP’s annual general meeting, which is held on the first Monday after Palm Sunday, as required by an Act of Parliament. She died 5 days too soon. She was, however, allowed an entry in Munk’s Roll (now known as Inspiring Physicians), the RCP’s series of obituaries or biographies of fellows of the Royal College of Physicians, starting from 1518 to the present day.

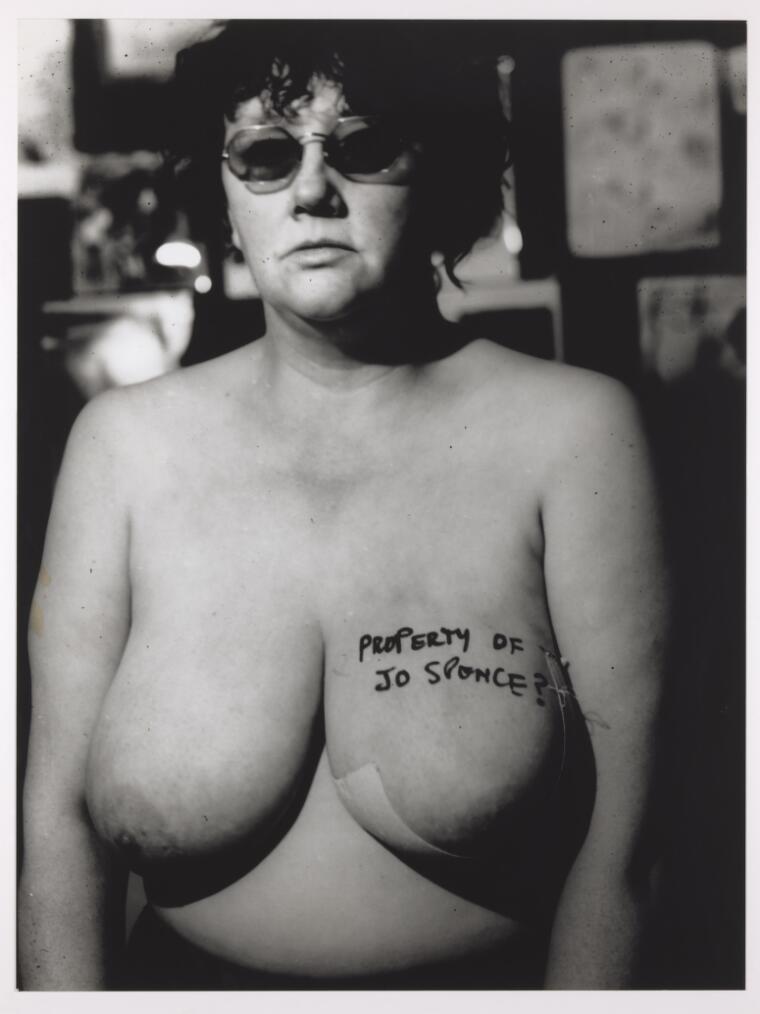

At around the same time, in 1982, the artist Jo Spence (1934–1992) was diagnosed with breast cancer. Both of these women were surprised by the impersonal treatment of their doctors. This influenced them to share their experiences. While we may expect an artist to share their feelings about cancer treatment, it is rarer to find this amongst doctors at the time.

Harris documented her treatment in an ostensibly anonymous article in The Lancet in March 1979. She wrote believing she was free from cancer because ‘clinically and by computerised tomography scan I am in remission from the disease’ – only to succumb a year later. As she wrote about the experience of her treatment – called the ‘horrors’ by her biographer – she held on to the hope that she would survive even though she knew she had ‘faced death’ and that she ‘may not now fulfil [her] ambition of being an old lady in a garden’.

Because of her poor experiences with her doctors, Spence chose alternative medicine rather than have chemotherapy after her surgery. She documented the process through photographs and these were featured in Wellcome Collection’s exhibition ‘Misbehaving bodies’, which closed on 26 January 2020.

RM Sánchez-Camus, a creative practitioner who develops works of art in collaboration with community partners, said in ‘Misbehaving bodies’ that:

‘In these photographs Jo Spence is sharing the processes of control enacted upon the body by the medical world and her own dignified autonomy to take back control and attempt to capture her body and heal it through alternative medicines. She reveals for us the mysteries of the liminal [or transitional] world of dying, in all its brutal physicality and vulnerability. In these images we see the fear and control but also the hope and resilience that is so universal in end-of-life care – the final hero’s journey of one individual’s epic tale.’

While the RCP does not have a comparable set of photographs or diaries by Harris, we have the photograph she submitted and biographical form she completed when she was nominated for fellowship of the RCP, while unwell. For many of the women in the RCP’s collection, their photograph and their biographical form is all that we know about them. The obituaries are commissioned after their death, based on the biographical form that they complete when they become a fellow.

The fellowship nomination was important to Harris and she appeared to be determined to see it through. Harris’s biographical form is handwritten but seems to have been completed by someone else because part of the signature is in a different hand. It is possible that her illness prevented her from writing and that she tried to sign it but only got as far as her first name. The same person who filled in the rest of her form appears to have completed her name.

‘Working with patients at St Christopher’s Hospice over six years, through the arts I have come to understand how this temporary moment in time called ‘dying’ engenders a powerful sense of self and a need to leave behind a legacy. To make a mark in the world and proclaim your existence to others before succumbing to the full breakdown of the machine that has until that point carried you through life.’

RM Sánchez-Camus

Along with the form, Harris submitted a small passport photograph. There are a surprising number of passport photographs in the RCP’s collection, which is to say that they are head and shoulders and facing the camera, usually taken in a booth. The passport photographs rules now are strict about how you are allowed to look, including not allowing smiling, but in the 1970s when many of these were taken they were an opportunity for women to be in control of their image. They didn’t have to do what a photographer wanted. It was cheap and they could immediately see the results and try again if they were not happy with it. It is a very informal medium, which seems at odds with the careers that physicians such as Harris had undertaken, the forms that the RCP asked them to complete and also the ceremony that they would attend to confirm their entry into the fellowship.

My first thought on seeing this photograph of Harris was that she didn’t see the value in a photograph that would immortalise her in Munk’s Roll. She is sitting slightly off centre, casually dressed, unsmiling and no special attention paid to hair or makeup. But really this is a portrait of someone who is completely at ease with her appearance and probably was the last time she felt this way.

The photograph isn’t dated and was most likely taken before she became ill in autumn 1977. Harris may not have been concerned about her appearance before, but she was acutely aware of the changes as a result of her illness. In The Lancet, she describes her appearance during her treatment as having ‘total hair loss, a generalised iridescent clay colouring of the skin and slight patchy dark pigmentation’.

'The diagnosis is the door into the world of dying that positions you as the subject in a journey into the unknown. … To be living as someone who is dying is to be, as mythologist Joseph Campbell termed, on a hero’s journey. Leaving behind the comforts and certainty of everyday life, the dying person has to re-evaluate and re-examine how they live, what they live for and who they are in relation to their imminent death. There is a powerful physicality in this process; the body is out of control.'

RM Sánchez-Camus

Many doctors, used to observing illness rather than suffering it themselves, find becoming a patient an eye-opening experience. This photograph alongside Harris’ biographical entry shows a doctor whose professional life became inextricably linked to her personal experience.

Nearly 30 years later, Kate Granger (1981–2016) started the #HelloMyNameIs campaign in 2013 while she suffered cancer. This is a campaign for more compassionate care that all three women lacked during their treatment. The key values of the #HelloMyNameIs campaign are: communication; the little things; patient at the heart of all decisions; and see me as a person first. They show that seemingly small things make a huge difference to how a patient feels and, in the case of Spence, the decisions that they make about treatment. Perhaps it is because acts of compassion can be so small as to appear insignificant that they are forgotten, and the lessons need to be relearnt over time. Harris and Granger may not have known each other but they shared similar experiences and their lives are threaded together through Inspiring Physicians to benefit patients in the future.

Corinne Harrison

LAMS officer