Miraculous medicines: cure-all ingredients in early modern European recipes

Dragon’s blood: fantastical and domesticised healing

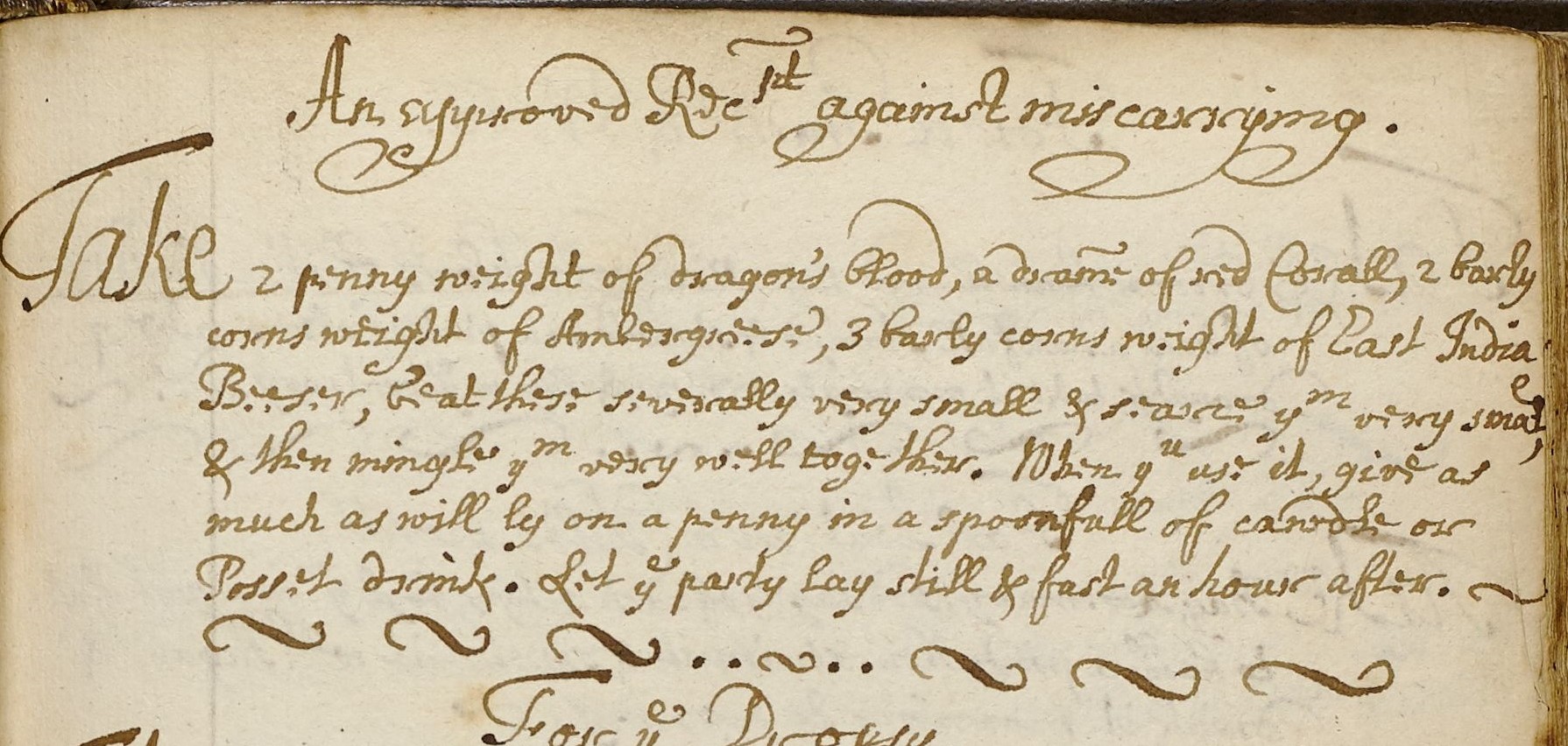

Curiously, a recipe book attributed to Mary Goodson in 1687 links dragon’s blood to women’s reproductive health. The entry entitled ‘An approved[?] receipt against miscarrying’ outlines a mixture of dry powdered ingredients, including first and foremost the dragon’s blood, which is then to be taken by the recipient with a spoonful of liquid; she must then lie still and abstain from eating for the next hour.

If ever an ingredient stood out as a fantastical farce, it is surely dragon’s blood. Mentioned as early as 50-70 AD in Dioscorides’s De Materia Medica, this ingredient—formed in lumps of dark-red resin or bright-red powder— became known as an antidote to many ailments. In De Materia Medica it was heralded for its ability to treat respiratory and digestive problems. By the medieval period, merchants emphasised its far-fetched origins and widened its compendium of cures. Merchants claimed that this really was the solidified blood of dragons, collected after the beasts were slain by their mortal enemies, elephants. Was this an attempt to increase the romanticism, or perhaps just drive up the price? You decide!

Goodson’s book (MS251) contains mostly culinary recipes but includes a few medical receipts, as was common in a well-to-do early modern household. Little is known about Goodson herself. This is often the case with the scribes of such recipe compilations as they were kept within families and passed through generations. Furthermore, women are not as widely documented in historical records, and we only have her (presumably) self-penned name to go on. Interestingly, there is also a dedication to a Molly Morgan at the start of the manuscript and potentially a second hand that appears in the latter part.

So, how did dragon’s blood make its way here?

There is of course no evidence for the mythical claims, but it would be foolish to dismiss dragon’s blood altogether. In fact (and by the 15th century it was widely understood), the resin comes from a blood-red tree sap; this was native to the Canary Islands and Morocco but has since been sourced from trees native to Asian countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia. It is still regarded today in herbal medicine for its proven antiseptic qualities, and it was recently found to contain taspine, which has antiviral properties. (It is fair to note, however, there have been no human clinical trials to assess its full effectiveness.) This bolsters the early modern belief that, in addition to respiratory and digestive problems, dragon’s blood was also excellent for treating wounds; there may be some truth in its historical promises, then.

Cure-all as it was, Goodson links dragon’s blood in her recipe book specifically to women’s reproductive health. This is not an entirely unique sentiment: it was first recorded by Trotula of Salerno, a fascinating medical group in the 12th century which is believed to have included at least one woman, named Trota. She identifies a concoction including dragon’s blood as being effective in treating menstrual problems, especially heavy or prolonged bleeding. Centuries later we see in John Quincey’s Pharmacopoeia Officinalis Extemporanea, contemporaneous with MS251, an entry citing dragon’s blood as an ingredient for creating a ‘plaster to prevent miscarriage’. Goodson’s entry is therefore representative of a historically wide and apparently accepted treatment.

Importantly, the entry in MS251 demonstrates the domestication of such a multi-faceted ingredient: from fantastic lands of slain dragons to the Goodson-Morgan household, dragon’s blood is an early modern cure-all ingredient that continues to intrigue. For example, the skincare industry today has adapted the combination of dragon’s blood’s soothing effects with its ability to produce collagen in the skin to create various serums and moisturising creams, typically marketed towards women with anti-aging promises. Not too far removed from the medieval pedlars’ branding techniques, then, the domesticised lure of dragon’s blood remains even today.

Jessica Reeves

Collections volunteer

References:

- Goodson, Mary, MS251

- Green, M.H., The Trotula: An English Translation of the Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine (Philadelphia, USA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), p.83

- Mount, Toni, Dragon’s Blood and Willow Bark: The Mysteries of Medieval Medicine (Gloucestershire, UK: Amberley Books, 2015), pp.119-20

- Quincey, John, Pharmacopoeia Officinalis Extemporanea (2nd ed.) (London, UK: 1719), p.598