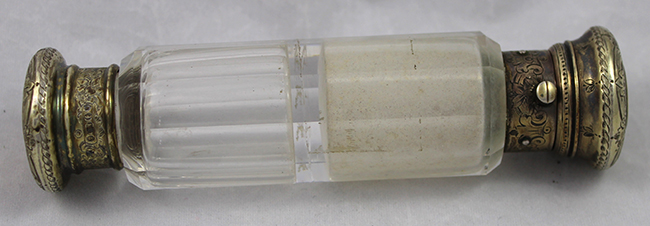

X694. An ivory handled pomander cane.

There has been a longstanding relationship between health and smell. In early civilisations smell was part of rituals and everyday life, for example through the use of aromatic herbs and incense. From ancient times in Europe and China, there was a widespread belief that diseases travelled through the air. This was called the miasmatic theory and good-smelling air was therefore very important.

Before the understanding of germs, bad or foul air was regarded as the cause of infections and the spreading of diseases. In fact, prominent scientists of that time believed that bathing was bad for one’s health, as water would soften the skin and weaken the flesh! From the 14th to the 18th century, Europe was affected by many plagues. To prevent further the spread of illness and to combat the stinking smell of sickness, bad smell was fought with the sweet smell of aromatics. Cities went as far as to build bonfires with aromatic scents in public places and accessories to overcome the stench of disease became popular.

The preventive power of good smell was also used by doctors, especially ones treating patients affected by the plague, to protect themselves from catching the disease. To avoid breathing the disease-causing odours, doctors in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries would wear a special beak-like mask. This mask was created by rolling a card and filling it with dried flowers, herbs and spices.

Doctors would also carry a cane with them, which for centuries has been a symbol of success for a physician. The more expensive canes had a vessel for a pomander within the handle, to prevent the doctor from smelling the foul air and becoming infected. An example of such a cane can be seen in the picture to the right. This is an ivory-handled pomander cane, dating from around 1830. It has a hollow handle into which aromatic substances are placed. With a cane like this, a doctor felt protected from catching a patient’s disease.