At 6pm on 19 February 1925, 5WA – a local radio station of the British Broadcasting Company (as the BBC was known until the end of 1926) – broadcast the live sound of a beating human heart to listeners in Wales and the south west of England.

The broadcast was a collaboration between 5WA, the Welsh National School of Medicine and the physiologist Ivan de Burgh Daly (1893–1974). The medical school’s Institute of Physiology, at which Daly was a lecturer, was at that time researching the magnification of heart sounds.

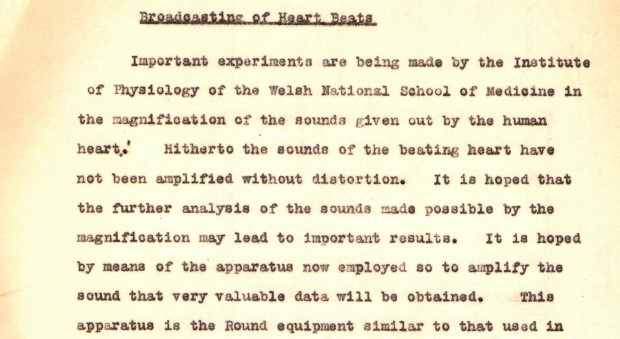

The transmission was intended to demonstrate the effectiveness of the new ‘Round’ apparatus for amplifying human heart sounds. Given the importance of accurately hearing the sounds, the press release issued prior to the broadcast instructs listeners to take ‘extraordinary pains in the adjustment of their [radio] sets to prevent interference’.

The press release is at pains to say that it ‘in no way proves that the broadcasting of heart beats will enable diagnosis of cardiac affections [sic] to be made at distance’. However, Dr John Henry Whitham wrote to Daly immediately after the broadcast to say that, even though he could only hear with his left ear, he heard the heart sounds on the broadcast from Cardiff with such clearness that he was able to diagnose the cases.

A collection of papers in the RCP archives preserves documents relating to the broadcast, including the press release quoted above, correspondence and photographs. The papers were given to the RCP archives by Michael de Burgh Daly (1922–2002), Ivan’s son, and himself a professor of physiology.

Though principally intended for ‘medical men’ to evaluate the usefulness of a new technique for amplifying the sound of the heart, the press release notes that:

Lay listeners, however, may find a certain thrill in hearing for the first time the highly magnified beat of a human heart being made audible simultaneously to hundreds of thousands of people.

The speed and other characteristics of the human pulse were a key feature of medical diagnosis for thousands of years, and observation of the sounds of the heart by direct auscultation – ie by placing the ear directly against the chest – is recorded as early as the era of the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates (c.460–c.370 BC). The sounds that a physician could hear were dramatically improved in the early 19th century when the French physician Renae Laënnec (1781–1826) invented the stethoscope and wrote treatises about its use.

The invention is regularly cited as a breakthrough in medical diagnosis, a means by which major improvements in identifying heart conditions were swiftly made. The distance between patient and physician created by the tube of the stethoscope was a step forward for hygiene and modesty for both parties. However, the stethoscope was not immediately welcomed by patients and the ‘new’ sounds it revealed were a cause of anxiety. Though the greater physical space between physician and patient was welcome, the new intimacy of clearly transmitted heart sounds was unsettling and disconcerting. The inner workings of the body were now audible as never before, and the heart – long viewed culturally as the seat of human emotion – was believed to contain more than just medical secrets.

‘Aren’t you going to listen to my chest, doctor?’

Some physicians note that patients today are sometimes sceptical about more advanced diagnostic tools such as the echocardiogram, a type of ultrasound scan, and instead express a preference for the great ‘authenticity’ of the physician listening directly to the body through a stethoscope. There is something reassuring, to the modern patient, about the physician being in direct contact and hearing the live sounds – those very sounds that in earlier years were the cause of alarm. It’s not necessarily the case that patients crave ever less physically-proximate methods of examination.

Considering these historical and modern attitudes has led me to think more closely about Daly’s 1925 broadcast. It’s notable that the patient whose heartbeat was transmitted to the nation barely features at all in what’s preserved in Daly’s papers. One photograph shows a trial run of the broadcast from November 1924, in which Daly’s technical assistant leans over a rather ill looking man lying on a couch with a receiver placed against his chest. The patient’s name, however, has not been recorded. What consent did he give to have his heart sounds broadcast? Did he feel the same thrill as the listeners? Or was he unsettled about the beating of his heart being shared with the nation?

Ivan de Burgh Daly’s ground-breaking live radio transmission of a patient’s heart sounds seems to foreshadow the fly-on-the-wall medical TV programmes we’re familiar with today. It occupies a place in a narrative of technological progress driving medical diagnosis and treatment. However, by considering it from the patient’s perspective, it also marks an interesting moment in the long history of changing relationships between the personal body and the physicians who examine and treat it.

Katie Birkwood, rare books and special collections librarian

This post draws on conversations at the Society of Apothecaries' Geoffrey Flavell Symposium 'The Heart, Health and Culture: An exploration in medicine and the humanities’, held on 29 June 2017, and on Melissa Dickson’s article ‘Thou simple tube’ in History today, 67:5 (May 2017).