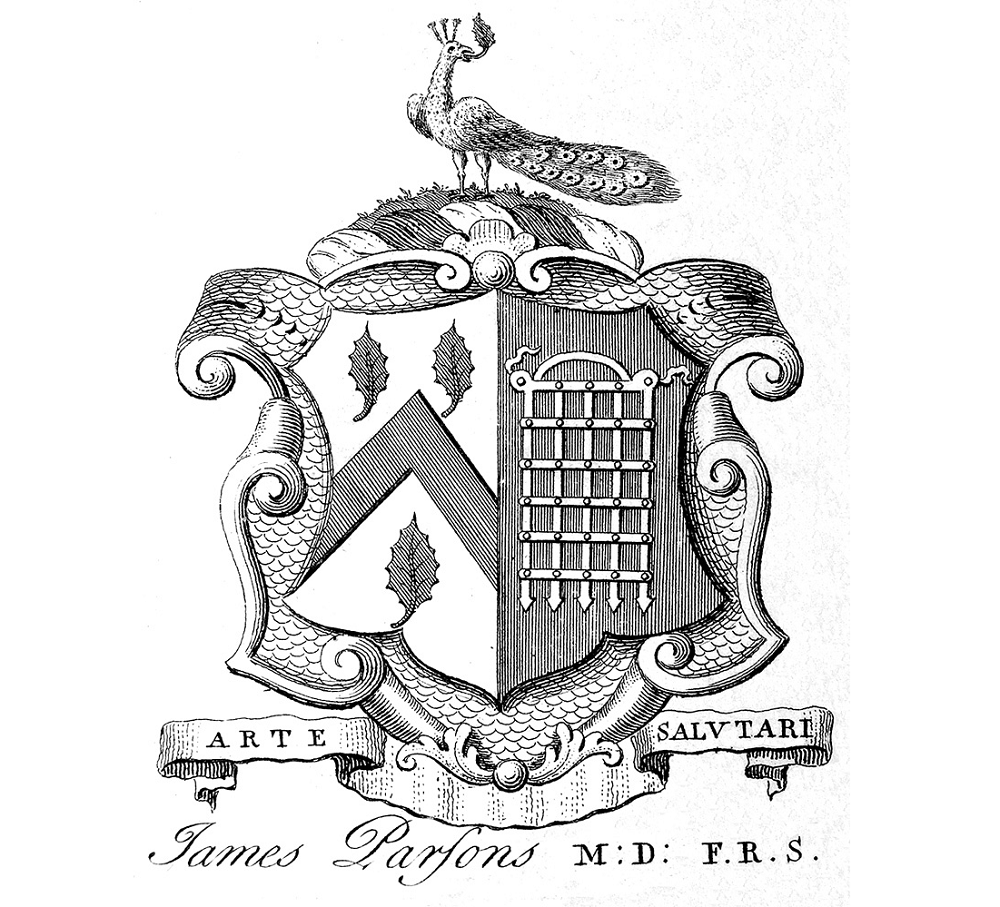

A bookplate, or ex libris, is a printed label used to indicate ownership of books, usually placed inside the front cover. Bookplates originated in Germany not long after the invention of printing. Early bookplates often incorporated the coat of arms of the owner but others were typographic labels. Bookplate is an Anglo-American term that came into usage in England towards the end of the 18th century; the term ex libris originated in France and is used universally in the non-English speaking world.

By the middle of the 18th century bookplates had become just one more of the iconic possessions of successful families, allowing the display of a line whether long borne or recently granted. It is not surprising that families with armorial porcelain (ceramics decorated with a coat of arms) were often the same as those with bookplates, for the latter performed the same function in the gentleman’s library.

The painting of arms is now become a serious business and I must either lose or gain a great deal of business by it – however, I must at all events, come into it!

Approximately 6,000 Chinese armorial services could have been made for the English-speaking market but so far only about 4,000 have been identified. The owners of these services were usually successful professional and merchant families and country gentlemen with inherited wealth. It is not difficult to see how these services became so popular, as one only has to see a display to appreciate how colourful and attractive they are. Chinese porcelain was about 10 times as expensive as other porcelains and thus a luxury only to be afforded by the very wealthy.

Orders for armorial porcelain were taken by sea to Canton, in China, by the East India Company. The centre for porcelain production was Jingdezhen, a city 600 miles from Canton by land and river. The Chinese merchants travelled between the two cities to place orders and any bookplates or other patterns were transported in this way.

It is thought that 15–20% of Chinese armorial services were derived from bookplates. Various methods were used to convey to Chinese craftsmen the arms that were to be illustrated. Sending a bookplate, preferably coloured, was a simple method. The safest method was to send a colour painting of the arms. Considering the distance, effort and expense involved in obtaining the porcelain it is surprising, in some instances, how little care was taken to ensure that the heraldry was clearly explained. In many cases the resulting porcelain carried arms that were to one degree or another imperfect. The Chinese painters made few errors but the few mistakes made were caused by inadequate instructions or colouring. Where bookplates were provided as patterns the arms were usually accurately depicted on the porcelain.

During the first half of the 18th century the painting and enamelling of the arms were carried out at Jingdezhen but later this was transferred to Canton. It could take years for orders to be delivered in Europe, but the delivery time speeded up once the painting and enamelling was done in Canton. Before then it often took longer than 2 years for the service to be delivered and in several cases the original client had died before the service was seen.

The identification of the porcelain services not infrequently throws light on the ownership of bookplates and vice versa. Interestingly, a few years before 1776, Josiah Wedgwood had been quoted as saying, ‘Crests are very bad things for us [potters] to meddle with’, pointing out that you can’t get rid of a crested piece as a second. How quickly Georgian tastes, and his views, changed!

Nigel Cooke, RCP fellow and museum volunteer

- Resources for more information about armorial porcelain and bookplates:

- Howard DS. Chinese Armorial Porcelain. London: Faber 1974

- Howard DS. Chinese Armorial Porcelain, volume II. Chippenham: Heirloom & Howard Limited 2003

- Latcham P. Bookplates and Armorial Porcelain.The bookplate journal 2008;6:2.

- The Bookplate Society