Medicine is certainly used for treating the human body, but on occasion the body itself becomes medicine—and perhaps shockingly to the modern reader, such occasion wasn’t rare. From bodily excretions to bones to ‘outlandish mummie’, these ingredients were commonplace enough to feature in domestic recipe books.

Bodily excretions were not the ‘disgusting’ topic they are today: it must be remembered that in a period less technologically advanced, often the only way to tell what was happening inside the body was through that which came out of it. Furthermore, the understanding of a ‘one fluid’ medical model meant that all excretions were believed to be the same substance, moved and transmuted through the body. Even so, we see different excretions credited for different healing properties. For example, in the RCP collection we see sweat cited as an ingredient for curing chapped lips and cramp; saliva for skin diseases and even for hair removal; and finally urine, for pregnancy tests and treating wounds inflicted by animals. There is even a curious entry advocating a woman in labour to drink her husband’s urine to induce placenta.

In historical context, this is no far leap from the ancient teachings still regarded in the early modern period. In Greece, Hippocrates advocated a ‘pollutant therapy’, which used impure human excretion to combat disease in the human body. In Rome, the power of gladiators’ sweat was so in-demand that women would purchase or collect vials of the substance, believed to hold various properties from being an aphrodisiac to a cosmetic/anti-ageing agent. Beauty serums that claim to be anti-ageing or to increase desirability are widely known today, but the belief in drinking hot blood from gladiators’ wounds to cure epilepsy is extraordinary.

If bodily excretions held such potency, why not go straight to the source— the body parts? We find two examples in the RCP collection of human bone being used in domestic medicine: to treat a ‘bloody flux’ (menstruation) and for the ‘falling sickness’ (epilepsy). Both recipes require the bone/skull to be ground into a fine powder (the skull powder must also be combined with the powder made from a dead jay bird for the latter), then mixed with wine (red and white for the former and latter respectively). We even have an attribution for the entry in Madam Pyne's recipe book to ‘Mrs Bond Dr Strouds mother’, but she wasn’t alone: King Charles II reportedly also enjoyed skull-and-wine, so much that the concoction was known as “The King’s Drops”. (For the teetotallers, a mix of human skull and chocolate, advocated by Thomas Willis, a 17th century pioneer of brain science, was thought to cure apoplexy.)

It’s impossible not to mention religion here: the consumption of Christ’s ‘body’ and ‘blood’ in the Eucharist was a common early modern ritual. Is it unreasonable to make the link between the spiritually symbolic and the viscerally literal? A 12th century bishop, Hugh of Lincoln, visited an abbey in Normandy where they held the relic of St Mary Magdalene’s arm. Not content with simply viewing, it’s reported he began to bite the bone in attempt to break a piece off. He was successful and— much to the horror of onlookers— walked away with two pieces to take back to Lincoln Cathedral. It can be debated whether he was driven by spirituality or a different kind of consumption—relics were known to bring your parish increased prestige and footfall. That said, he reportedly maintained that his bold act was noble and no different to honouring God through the Eucharist.

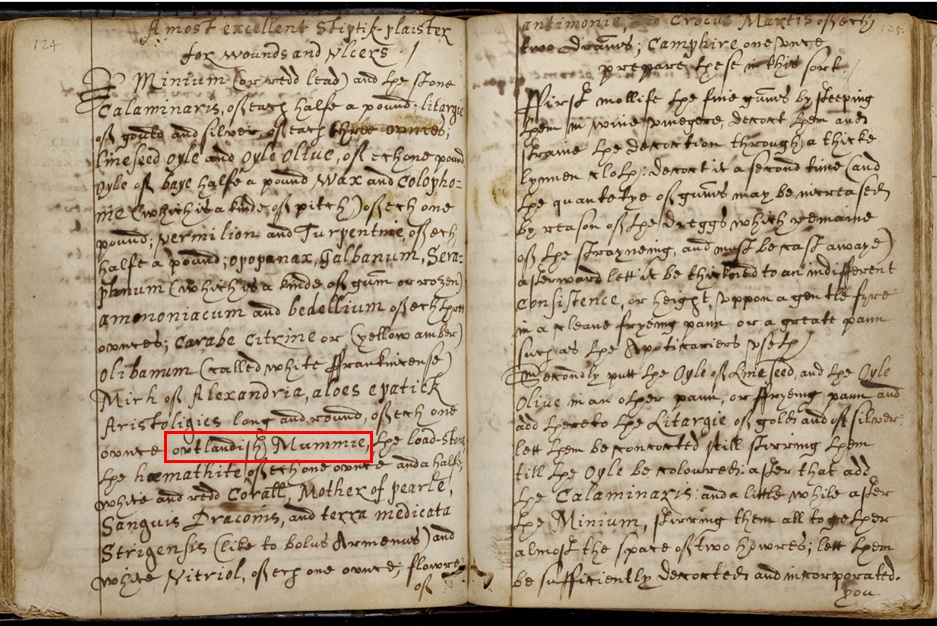

Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that the recipe using the body as ingredient in the RCP collection with the largest list of ‘virtues’ (i.e. cures, and thirteen to be exact), ranging from ruptures to cancer, contains mummy itself. Sarah Wigges' recipe book outlines a detailed entry to make ‘a most excellent stiptik-plaister for wounds and ulcers’, calling for a mixture of various oils, wax, turpentine, frankincense, myrrh, and of course the ‘outlandish mummie’. In this context, ‘outlandish’ suggests ‘from far away’, adding for Western domestic consumers exoticism and maybe even romanticisation to such an ingredient. First popularised in Arabia, the definition of mummy (or mummia, mumiya) wasn’t fixed, and by the 11th century it came to mean any part of a preserved human corpse. This travelled to the Western world, but without the practice of mummification, such a substance wasn’t easy to come by—the idea of creating fresh mummy took shape. By the early modern period it was defined as “a medical preparation of the remains of an embalmed, dried, or otherwise ‘prepared’ human body that had ideally met with sudden, preferably violent, death”, and was an important medical commodity from the 12th to 18th centuries.

There were not only recipes that included mummy, but indeed there were recipes for making mummy. Most notably, alchemist Oswald Croll goes into gruesome detail in his Basilica chymica of 1608:

Take the fresh corpse of a redhaired, uninjured, unblemished man, 24 years old and killed no more than one day before, preferably by hanging, breaking on the wheel or impaling… Leave it one day and one night in the light of the sun and the moon, then cut into strips. Sprinkle on a little powder of myrrh to prevent it from being too bitter. Steep in spirit of wine for several days. As the foulness of it causes an intolerable humidity in the stomach, it is a good idea to macerate the mummy with oil.

We also see myrrh as a key ingredient to prevent bitterness. Another parallel worth highlighting is the importance of, to quote from the Pharmacopocia Latina, the remedy’s ‘great force’: the mummy-plaster will keep its ‘vertue and strength’ for fifty years, when it will be ‘of as great force as when it was merely made’. Life force, or spirit, is an essential concept, ensured by the “sudden […] death” in the definition above. The notion is that the body best maintains its vitality before it has had a chance to fall victim to illness or simply old age. For an ingredient with such inherent violence to become so domesticised as to appear in recipe books also highlights a European cognitive dissonance. Contemporaneous outrage at indigenous peoples in North and South America supposedly performing ritualistic cannibalism (as told by European travellers) is undercut and an unsettling notion of not just cannibalistic consumption, but also commodification emerges.

Finally, what were the social implications? To source human ingredients, people often turned to bodies that, when alive, society regarded with little to no value. Public executions, for example, provided a great source of bodies for medical use (e.g. dissection) and consumption. We therefore see a dehumanisation and commodification that sadly hasn’t completely disappeared today when looking at the illegal organ harvesting market. The ideology behind mummies perpetuated ingrained misogynistic views of the time, too: the most valuable form of mummy, due to its ‘purity’, was the fille vierge (the virginal female). Yet, in sum, can we ignore the theory of the healing body behind it? Of course, we have progressed from the ingestion of human body parts as medicine, but can we see here the formation of what would become the life-saving breakthroughs of blood transfusion and organ transplantation? Technology has advanced our practices, yes, but maybe the hypothesis was there all along.

Jessica Reeves, archives volunteer

—————————————————-

Sources:

- Croll, Oswald, Basilica chymica (1608)

Dolan, Maria, The Gruesome History of Eating Corpses as Medicine (2012)

- Duffy, Eamon, Treasures of Heaven at the British Museum (2011)

- Gordon-Grube, Karen, ‘Anthropophagy in Post-Renaissance Europe: The Tradition of Medical Cannibalism’, American Anthropologist 90.2 (1988)

- Noble, Louise, Medicinal Cannibalism in Early Modern English Literature and Culture (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011)