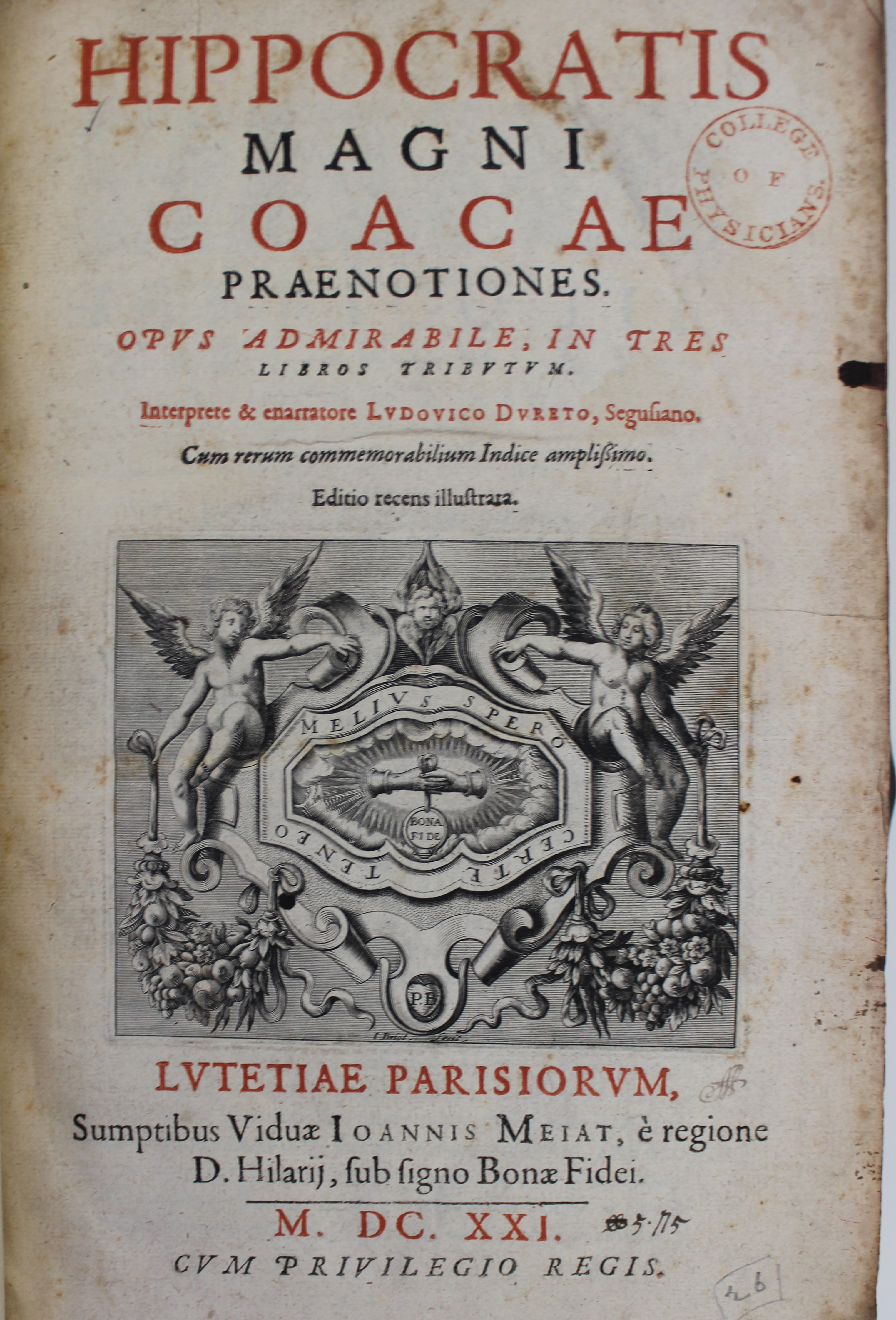

Title page of Hippocratis magni Coacae praenotiones. Published Paris, 1621.

The book in question is the Coacae praenotiones, or Coan prenotions, meaning ‘presentiments or precognitions from Cos’. It’s a collection of statements about prognosis in disease, attributed at the time this copy was printed to Hippocrates, but now believed to have pre-dated the main works attributed to this ancient Greek physician. Each statement is given in Greek and Latin, with lengthy commentary added by the book’s editor, the French physician Louis Duret (1527–1586).

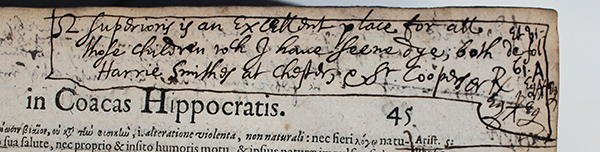

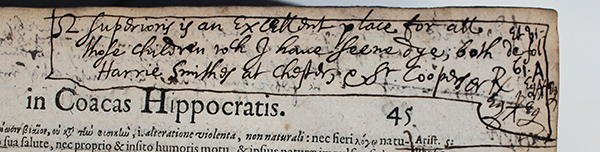

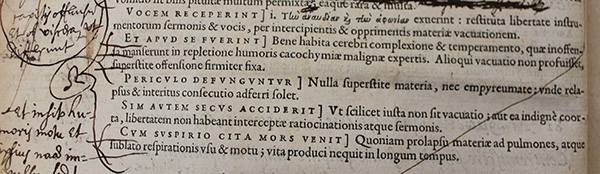

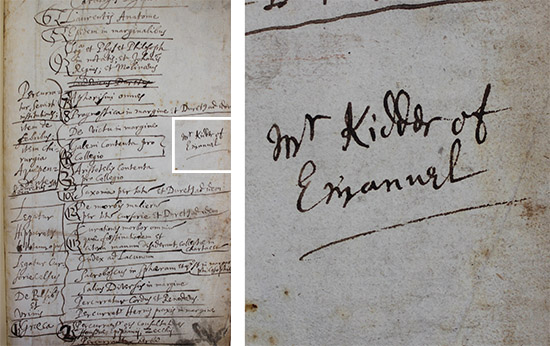

Notes like these are a rich resource, but they aren’t always easy to interpret. Not only is there the issue of changes in handwriting styles, and the quality and clarity of any person’s individual script, it’s no simple task to decipher and untangle what the words say or what the comments really mean.

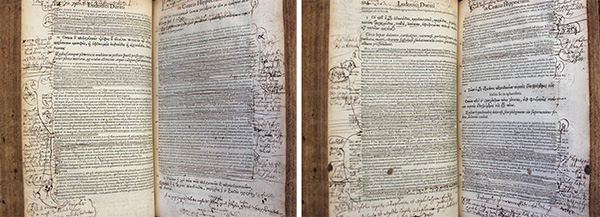

These annotations in this particular copy are written quite enthusiastically, and not particularly neatly, but the hand is pretty legible. There are notes in English, Latin and Greek, often combining more than one language in a single spot.

Dipping in on almost any page reveals how closely our reader was working through the text: letters and symbols are used to link points in the text with longer comments where space allows. The reader links recommendations in the text to their own personal medical experience, mentioning names and places.