Addressing colonial and exploitative histories in the RCP Archive, Heritage Library and Museum collections

This post contains potentially distressing discussion of enslavement and historic medical experimentation.

The RCP is a very old organisation, founded in 1518. It has historically been an organisation of well-educated, high-status and frequently wealthy individuals, which until the early 20th century was made up almost entirely of White men. Today, Black people are still under-represented in the RCP leadership, as they are in medical consultant positions, and racism in medicine is still a pervasive problem.

In 2020 the RCP commissioned a report on diversity and inclusion at the RCP, and the organisation has been working to implement the recommendations that came out of this. In light of this, and of a wider heritage sector focus on addressing and problematising the power structures inherent in museums, archives and libraries, the Archive, Heritage Library and Museum Services team have been working on ways to acknowledge and address the presence of exploitative structures and unrepresentative histories within the collections.

The collections and stories held in the RCP archive, heritage library and museum (AMS) have been built up over the organisation’s long history, including many items donated during Britain’s highly exploitative colonial history. What has/not been collected and preserved, how these items have been presented, and whose stories have been told (or not told) are actively influenced by the people involved and by the societal structures in which they lived. As such, the influences of colonialism, racism, sexism and numerous other discriminatory ways of thinking from across the RCP’s long history are embedded in the collections. This means that items related to individuals who were White, male, able-bodied, cis-gendered and heterosexual make up the vast majority of the collections; histories of others are either absent or shown in a negative way.

The aim of the work to address exploitative histories is to uncover hidden and obscured stories in the collections, and to show that previous ways of presenting collections do not tell the whole story. This is to enhance our understanding, to increase the stories that we are able tell through the collections, and to acknowledge that unquestioning perpetuation of past views and approaches can have real, negative impacts on present-day individuals and communities.

The work done by the Archive, Heritage Library and Museum Services team so far is a small step in addressing the issues mentioned above, and much more can be done in future.

The work comes under two main strands:

- Developing guiding principles for work with collections

- Reviewing and updating information held about items in the collections.

A guidance document has been created to assist staff in writing sensitively and accurately about colonial and discriminatory histories, and four guiding principles have been drawn up:

- Words matter

Committing to recording information about collections items and writing content about them that is sensitive, accurate, and that avoids perpetuating structural violence and harm - Discover the whole story

Ongoing research into discriminatory and ‘hidden’ histories, to tell stories of underrepresented groups and tell more nuanced versions of already presented stories - Mind the gap

Recognising that the collections are not representative of all peoples linked to the stories/histories being told. We aim to address and minimise these gaps by future collecting - The work continues

Commit to expanding and improving the context of our catalogues and interpretive work on a continual basis, based on the actions outlined below and based on user feedback

-

Improving information held about items in the collections

Information about the RCP’s cultural assets is held in a variety of places; on the heritage library and archive and museum catalogues, on the museum website, and on a number of external sites. The team have focussed on a number of different areas in order to improve the information available about collections items.

Acknowledging colonial and discriminatory histories

The RCP collections contain items relating to topics, ideas and terminology that we now recognise as discriminatory, and which have far-reaching impacts that still affect people today. For example, racism and sexism in medicine; physicians’ involvement in slavery; histories of mental health and disability; pseudo-sciences such as eugenics and physiognomy; and past medical terminology.

Acknowledging the presence of these ideas and language is an important step towards making our collections accessible to all. To make people aware of what they may encounter in the collections, we have added advisory notices to the public catalogues and to the Inspiring Physicians database to flag that these may contain inappropriate and offensive language and attitudes.

There is also now a publicly available document listing individuals in the RCP collections who had connections to the transatlantic slave trade – many donors, contributors, creators and subjects of items in the RCP collections had links to slavery.

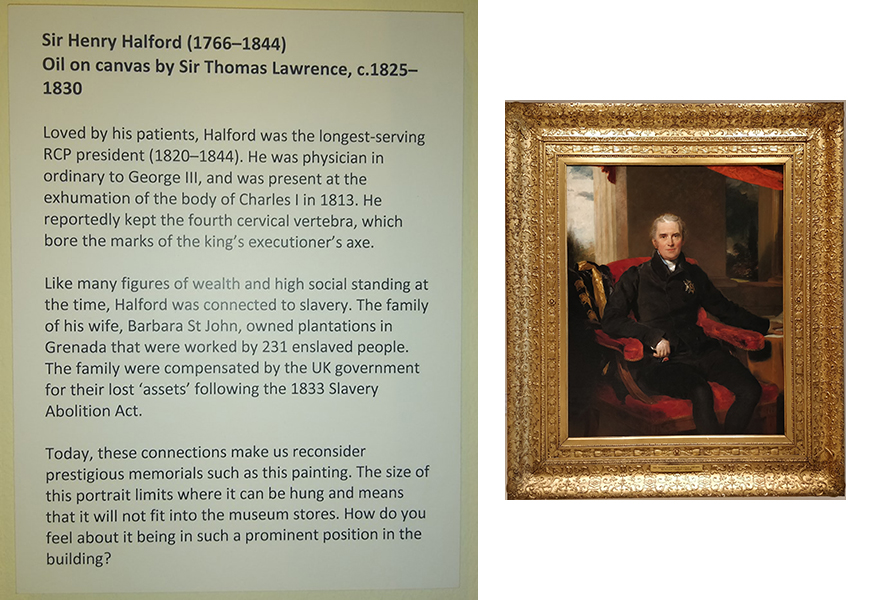

In the 11 St Andrews Place building, captions of relevant paintings have been updated to show the complexities behind these lauded individuals, for instance that of Henry Halford in the Lasdun Hall.

Updating terminology

We do not make changes to the terminology used in collection items themselves (no one is scrubbing out words in old documents), but we can change the language used to describe them.

Collection items and the catalogues that record information about them contain terminology we now recognise as discriminatory and as perpetuating prejudice, stigma, intolerance and exploitation. It is important that we provide historical accuracy and present a true image of the past. However, past language can have a negative and violent impact on people today, and so inappropriate language should not be used simply to preserve historical realism.

The Archive, Heritage Library and Museum Services team are updating the information held about the collections to make it clear when terminology comes directly from the historic item itself (e.g. where a document title contains an inappropriate term) and to remove inappropriate terminology from catalogue descriptions. Previous forms of the information are retained in the catalogue back-end as a record of what has changed.

Improvements to catalogue descriptions have also been made to:

- add modern terms to colonial place names

- write more sensitively about topics such as enslavement, race and ethnicity, disability, gender non-conformity, and religious intolerance

- centre the experiences of patients (rather than them being described in terms of their condition or treatment)

- to add in names and biographical information about women previously described solely as ‘wife of’.

The team have also investigated how far we can update content that is hosted externally and are implementing similar changes where possible.

Adding context

Improving our understanding of the stories held in the collections can help to highlight what stories are not being told and can show new perspectives on those that are already present. What is not said is often significant, and adding a broader historical context can provide a lot of information that was not previously evident. For example, this is the previous catalogue description about American physician James Sims:

‘Portrait of James Marion Sims (1813 – 1883) engraved by H.B.Hall jnr. Sims was a surgical pioneer and considered the father of American gynecology’

The description has been updated and now reads:

‘Portrait of James Marion Sims (1813 – 1883) engraved by H.B.Hall jnr.

Sims was an American physician in the field of surgery. In 1876, he became president of the American Medical Association, and in 1880, president of the American Gynecological Society.

Sims was a slave owner and doctor in Alabama and wanted to find a cure for vesicovaginal fistula - a tear from the inside of the vagina to the bladder as a result of prolonged obstructed labour. Between 1845 - 1849 he repeatedly performed experimental surgery without anaesthetic on enslaved women Anarcha, Betsy and Lucy, as well as on a number of other enslaved women whose names Sim did not record. It is unverifiable if the women gave their medical consent to Sims' surgical experiments, as consent from their enslavers, who had a strong financial interest in their recovery, was the only legal requirement of the time.

Despite Sims' involvement in human experimentation on enslaved women, the Sims vaginal speculum and rectal examination position remains named after him in modern gynaecology.’

Another example:

'Portrait of Alexander Pearson (d 1836) engraved by W. Holl after G. Chinnery. Pearson was senior surgeon to the East India Company in Macao and pioneered the use of vaccination in China. From the collection of Sr Arnold Chaplin.'

With some added contextual information becomes:

‘Portrait of Alexander Pearson (d 1836) engraved by W. Holl after G. Chinnery. Pearson was senior surgeon to the East India Company in Macao. In 1805 Pearson introduced smallpox vaccination in Macao and Canton [Guangzhou]. From the collection of Sr Arnold Chaplin.

The East Indian Company was an English, later British company that formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, and later with the Qing Dynasty. The company participated in the slave trade, and colonised parts of Southeast Asian and Hong Kong after the First Opium War.

Source: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/features/what-was-the-east-india-company’

The historical context and power structures within which Sims, Pearson and others were working are important, particularly as they relate to British colonialism within which a lot of the RCP collections were created or collected. This context helps us understand what was happening at the time and can help us see the power dynamics that were at play in the past. The power structures of racism and slavery meant that Sims, as a wealthy, White slave-owner, was able to carry out non-consensual, tortuous experiments on Anarcha, Betsy, Lucy and their peers, and yet has been remembered as a ‘surgical pioneer’. The names of many of the women who suffered in these so-called ‘pioneering’ experiments are lost to history, their identities and their pain erased.

Looking at the second example, again the context is important. Consider a doctor from Canton doing what Pearson did. How easy would it have been for this Chinese doctor to travel to Britain, introduce a Chinese medical practice, and be considered significant enough by those recording events to be remembered as a ‘pioneer’ two hundred years later? We have many White European men recorded as pioneers of various things in the RCP collections, but a scant handful of anyone else.

Future development

The work done on colonial and discriminatory histories in the RCP collections is just a starting point; we recognise that this improvement work will be an ongoing project. Immediate future activities include:

- Updating policies to make experiences of under-represented groups a collecting priority (for example portraits of Black physicians)

- Continuing to revise catalogue descriptions and display text to address inappropriate and offensive language and attitudes and to add more contextual information

- Improving subject tagging in the catalogues to make clear the extent to which collections cover topics such as slavery, scientific racism and eugenics, and disability.

Looking further ahead, longer-term future activities could include outreach work to include broader groups in the production of information about the collections, interpretation and public programming, and recruiting individuals with a range of backgrounds to review the work done by Archive, Heritage Library and Museum Services staff.

As a team we are aware that our experiences and cultural backgrounds do not represent the full diversity of society. As such we welcome input from visitors, Members, Fellows, RCP staff, researchers and anyone else. You can get in touch at history@rcp.ac.uk